Insights from a Probability-Based and Nationally Representative Survey

Key Findings

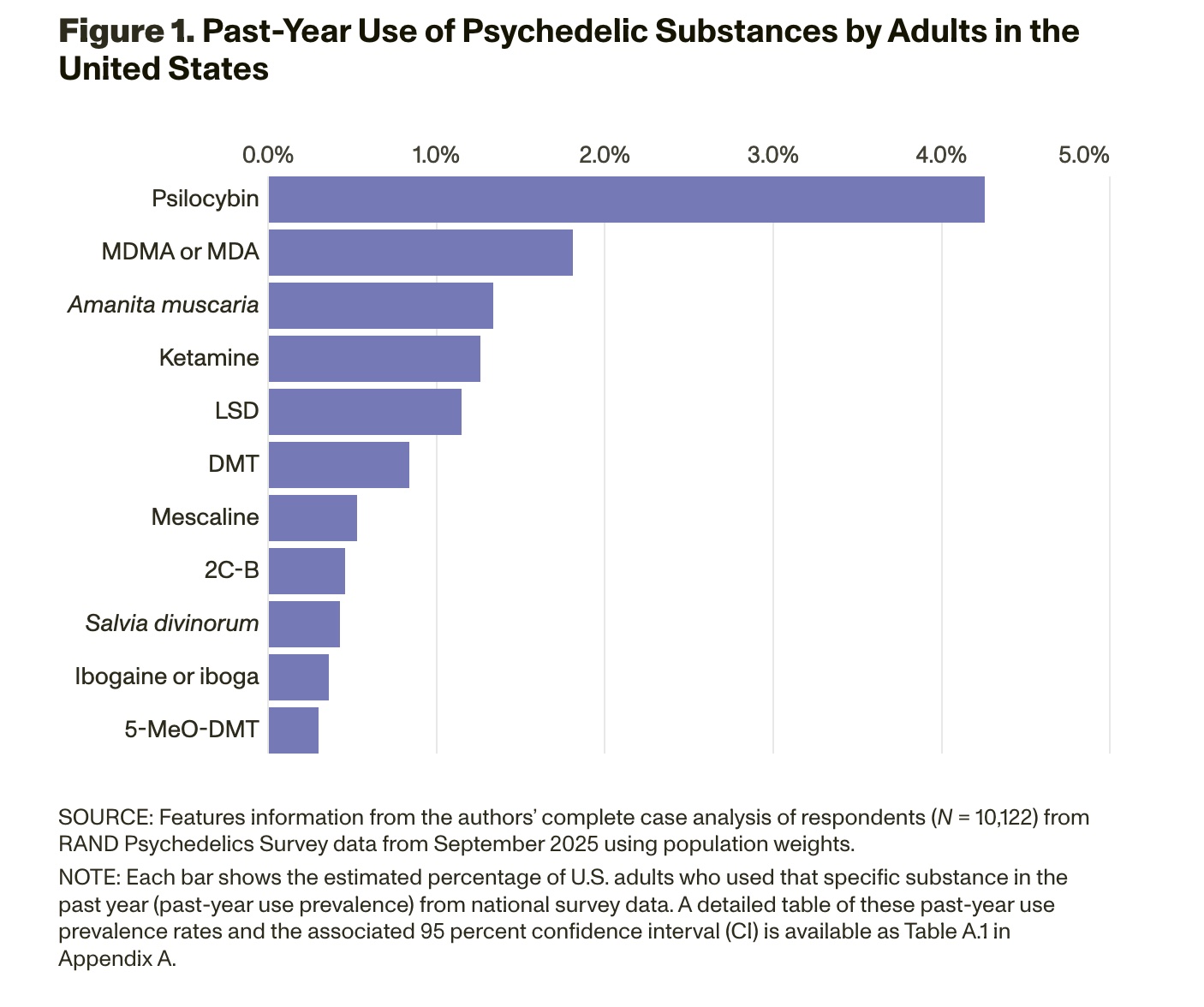

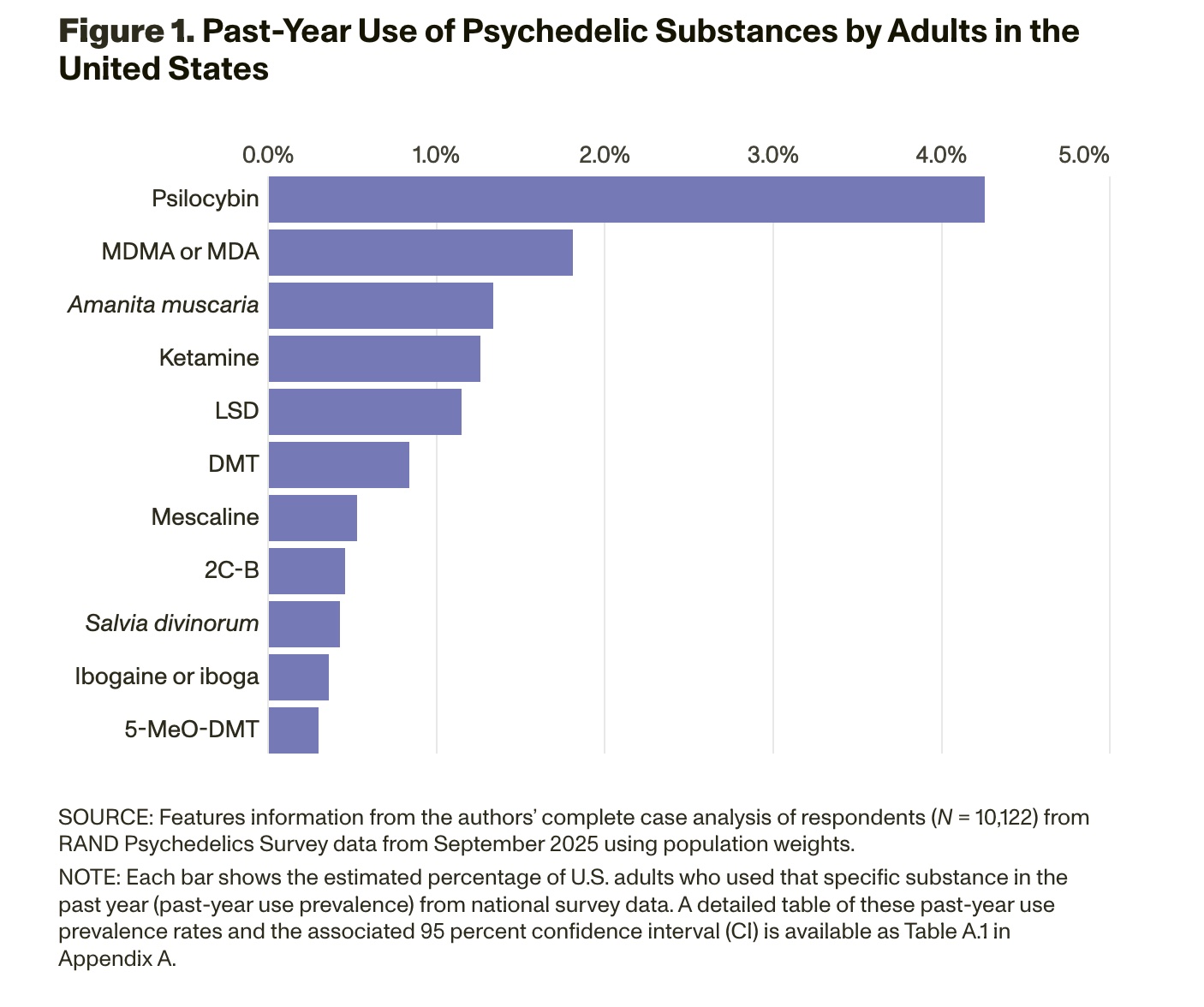

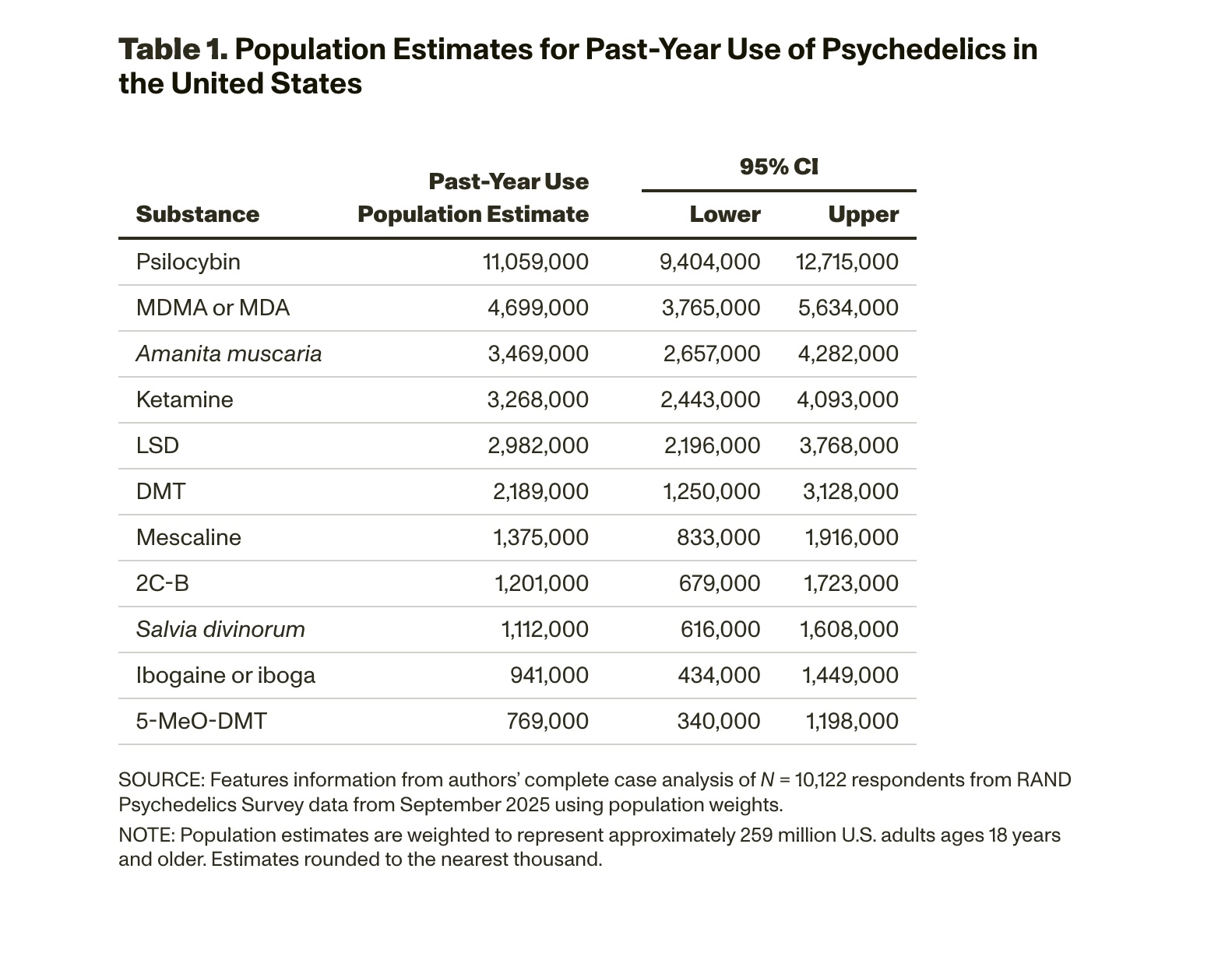

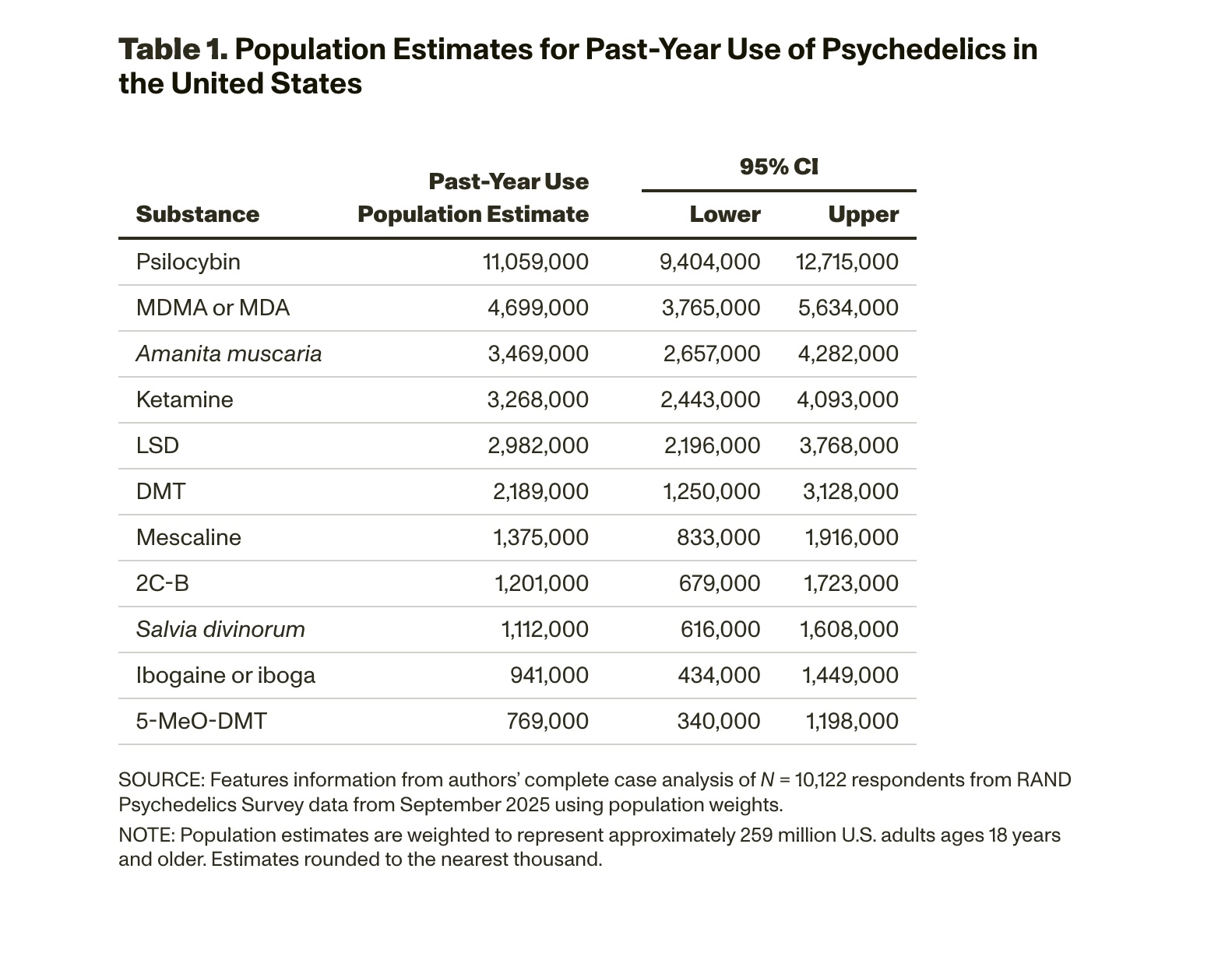

- The top five psychedelic substances used by U.S. adults in the past year were psilocybin, MDMA, Amanita muscaria mushrooms, ketamine, and LSD.

- Psilocybin was the most used psychedelic substance, with approximately 11 million U.S. adults using it in the past year.

- Approximately 10 million U.S. adults microdosed psilocybin, LSD, or MDMA in the past year.

- Among U.S. adults who used psilocybin in the past year, 69 percent microdosed at least once during that period.

- The aggregated number of days that U.S. adults used psilocybin in the past year exceeded 200 million, and nearly half of these days involved microdosing.

This is the first report from the 2025 RAND Psychedelics Survey, which was fielded in September 2025 to a probability-based, nationally representative sample[1] of 10,122 adults ages 18 years and older living in the United States at that time. This report presents top-line results on the use of 11 psychedelic substances and detailed information about microdosing (i.e., taking a small fraction of a full dose, often intermittently on a schedule) for psilocybin, LSD, and MDMA. These results should be of interest to those contemplating changes to psychedelics policies, researchers interested in use patterns (especially for microdosing), and others interested in learning more about these substances.

Background

Psychedelic substances[2]—such as psilocybin mushrooms, MDMA, LSD, and ibogaine—have long been touted as holding promise for treating various mental health conditions. Although medical research into the potential benefits and risks of psychedelic substances has increased, there is still a lot to learn about the use of these substances outside clinical settings. There is some evidence that the use of some of these substances, especially psilocybin mushrooms, is increasing in the United States (Rockhill et al., 2025). Although the supply and possession of many psychedelic substances are federally prohibited in the United States—with some exceptions (see Kilmer et al., 2024)—increasing numbers of U.S. states and localities have changed or are considering changing their policies on some psychedelic substances (Andrews et al., 2025). Additional data on the use of these substances in the United States are needed to inform policy debates.

Dosing practices are an area of particular unknowns with potential health implications. Psychedelic substances are sometimes taken in microdoses. Microdosing is defined as taking a small fraction of a full dose, often on a schedule over multiple days or weeks (Marks et al., 2023). Although there is no official standard for what constitutes a microdose, a commonly used measure is 10 percent or less of the regular dose one would take to feel the full perception-altering effects of the substance (Szigeti et al., 2021). A nationally representative survey fielded in 2023 found that about 47 percent of those who used psilocybin mushrooms in the past year reported microdosing the last time they used the substance (Kilmer et al., 2024).[3] Those who microdose report doing so for many reasons, ranging from managing anxiety and depression symptoms to improving mood and creativity (Nutt, 2024; Lea et al., 2020). A few clinical trials have focused on microdosing (e.g., Petranker et al., 2024; Murphy, Muthukumaraswamy, and de Wit, 2024; Mueller et al., 2025), and one review of the microdosing literature has called for more research on implications for cardiac fibrosis and valvulopathy (Rouaud, Calder, and Hasler, 2024).

Some other national surveys ask respondents about their use of psychedelic substances, but each has limitations. Additionally, the consumption of psychedelics by U.S. adults is rapidly changing, creating a need for the most-current data as possible. The National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), which recently released top-line results for 2024, is the main source of nationally representative data on substance use and includes some questions about recent use of some psychedelics (e.g., past-year use of psilocybin was added in 2024) (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2025). However, the NSDUH does not cover all substances that are part of current policy discussions—for example, specific questions about the use of ibogaine are not included in NSDUH. Another source, the National Survey Investigating Hallucinogenic Trends (NSIHT), also collects data about past-year use of psychedelics from a nationally representative sample, but neither the NSDUH nor NSIHT has reported data about microdosing psychedelics (Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Safety, 2025).

This report contributes to existing nationally representative data sources with population-weighted estimates of past-year use of psychedelics by U.S. adults from data collected in September 2025. We estimate the proportion of adults in the United States who have used a variety of psychedelics in the past year, including psilocybin, MDMA, ketamine, LSD, and Amanita muscaria mushrooms.[4] Then, we present groundbreaking estimates for how many U.S. adults have microdosed psilocybin, LSD, and/or MDMA in the past year. We also show a comparison of the number of days that U.S. adults used psilocybin, LSD, and MDMA in the past year and what share of those days involved microdosing.

All estimates in this report are based on self‑reported survey data. For simplicity of presentation, we refer to these responses as use in this report, although these responses represent respondents’ self‑reports rather than confirmed use. Readers should also note that microdosing can be difficult to define and whether individuals microdosed is self-reported in these data. See Appendix A for a discussion of additional limitations, tables that show the data used to create the figures, and methodological details about the statistical analysis.

Psilocybin Was the Most Used Psychedelic in 2025, and Amanita Muscaria Mushrooms Are Also in the Top Five

We asked respondents, “Have you ever used any of these substances in your lifetime? Select yes for any substance you’ve ever used, even if you only tried it one time or it was many years ago.” The list of substances consisted of alcohol, cannabis, and a variety of psychedelic substances. For respondents who reported that they had used any of these substances, we then followed up with questions about how recently they had last used the substance. Figure 1 shows past-year use rates, and Table 1 shows population estimates for the use of the following psychedelic substances:[5]

- psilocybin mushrooms (also known as magic mushrooms) or synthetic psilocybin—not including Amanita muscaria mushrooms (also known as fly agaric mushrooms)

- MDMA (also known as ecstasy or Molly) or MDA

- Amanita muscaria mushrooms (or fly agaric mushrooms)

- ketamine

- LSD (also known as acid)

- DMT (also includes ayahuasca, huasca, or yagé)

- mescaline (also known as peyote or San Pedro)

- 2C-B or other synthetic phenethylamines

- Salvia divinorum (also known as diviner’s sage)

- ibogaine or iboga

- 5-MeO-DMT (also known as 5 or toad).

Psilocybin stands out with a past-year prevalence rate of 4.26 percent, approximately 11 million U.S. adults.[6] Other psychedelic substances in the top five for past-year use are MDMA/MDA (1.81 percent—approximately 4.7 million U.S. adults), Amanita muscaria mushrooms (1.34 percent—approximately 3.5 million U.S. adults), ketamine (1.26 percent—approximately 3.3 million U.S. adults), and LSD (1.15 percent—approximately 3 million U.S. adults).

Approximately 10 Million U.S. Adults Microdosed Psilocybin, LSD, or MDMA in the Past Year

We asked respondents who reported using psilocybin,[7] LSD, or MDMA in the past year how many days in the past year they used each substance and how many of those days they microdosed. We defined microdosing in the survey questions as “taking a small fraction of a regular dose (a subperceptual dose) that is much lower than you would take to ‘trip’ or hallucinate on these substances.” Although our survey only asked questions about microdosing for psilocybin, MDMA, and LSD, there are also reports of other psychedelic substances listed in Figure 1 being microdosed—for example, ketamine and Amanita muscaria (Syed et al., 2024; Leas et al., 2024).

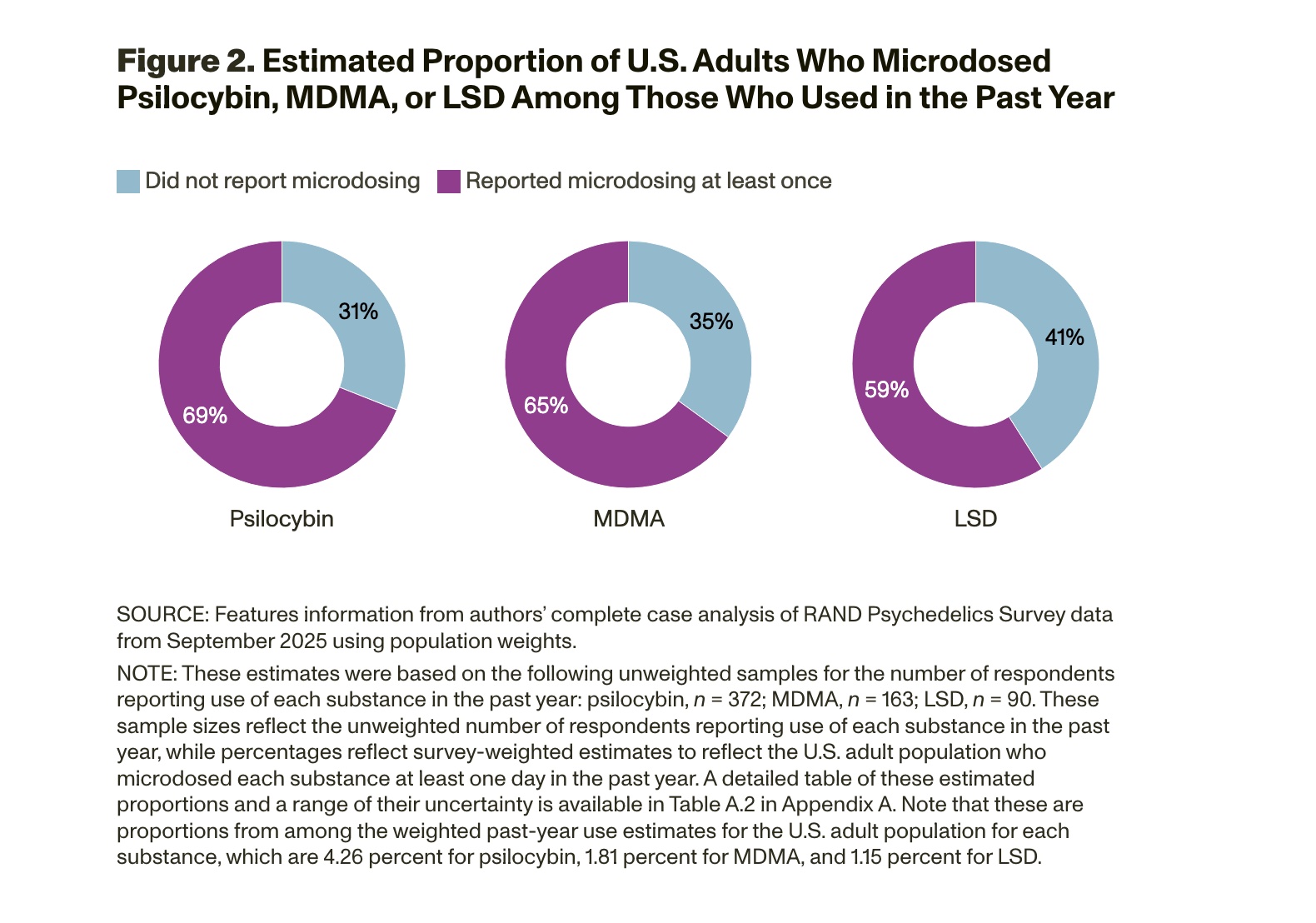

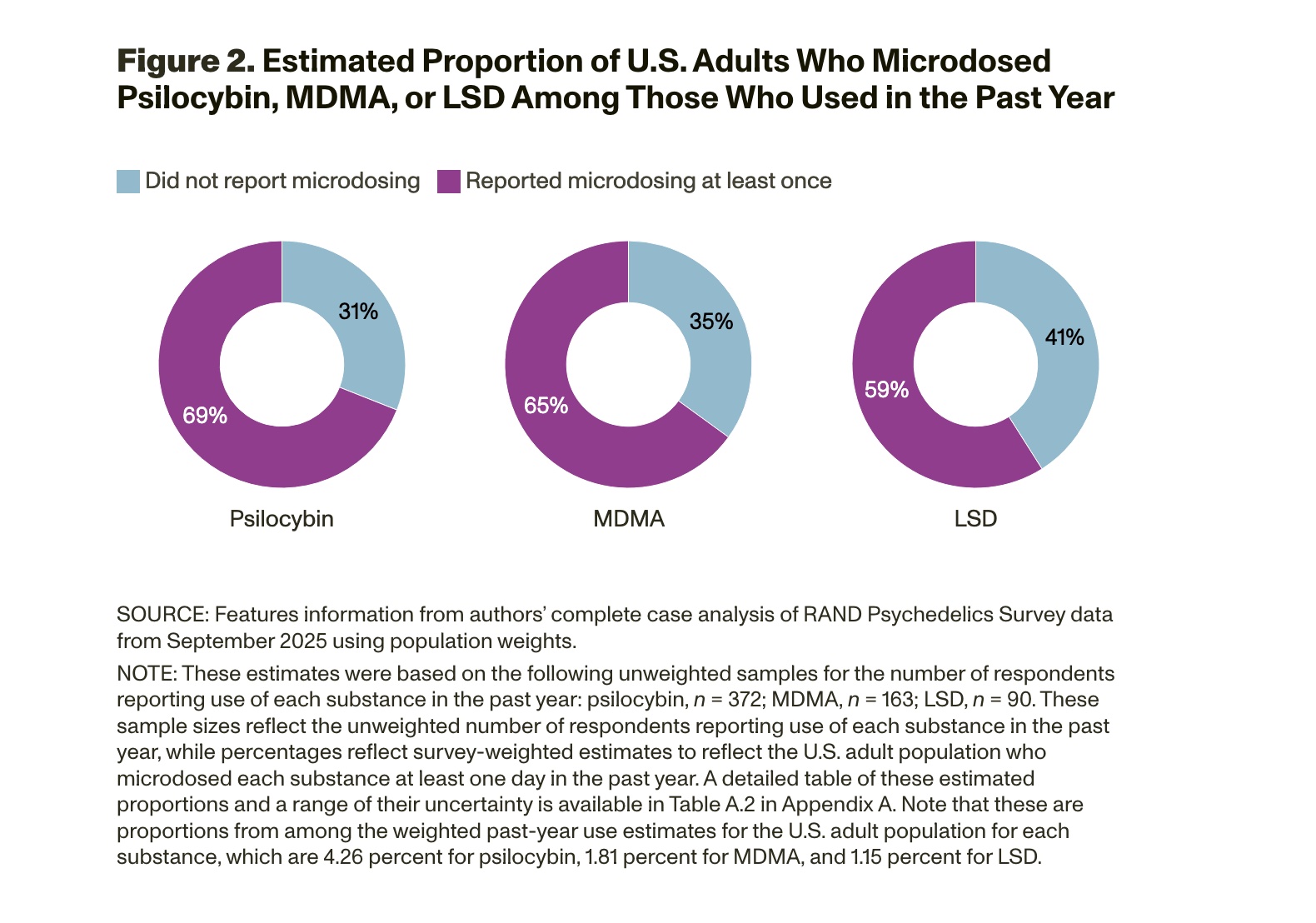

Figure 2 shows weighted estimates of the proportion of U.S. adults who have microdosed each substance at least one day in the past year, according to the 2025 RAND Psychedelics Survey data. Among U.S. adults who reported using each substance in the past year, we estimated that 69 percent microdosed psilocybin, 65 percent microdosed MDMA, and 59 percent microdosed LSD at least one day.

According to survey responses, we estimated that approximately 9.55 million U.S. adults microdosed one or more of psilocybin, MDMA, or LSD in the past year (about 3.7 percent).[8] This total reflects an overlap-adjusted estimate of unique individuals who microdosed.

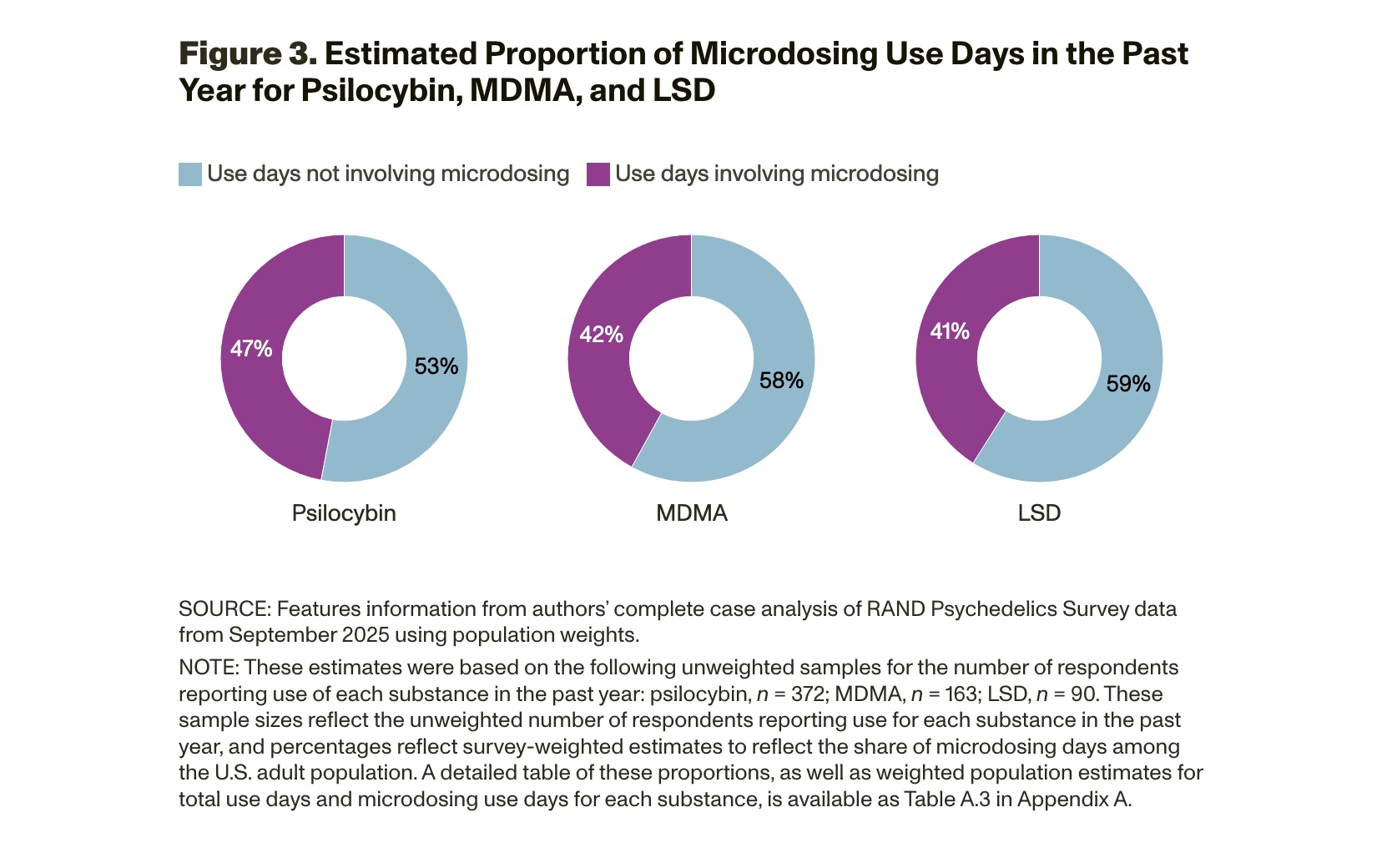

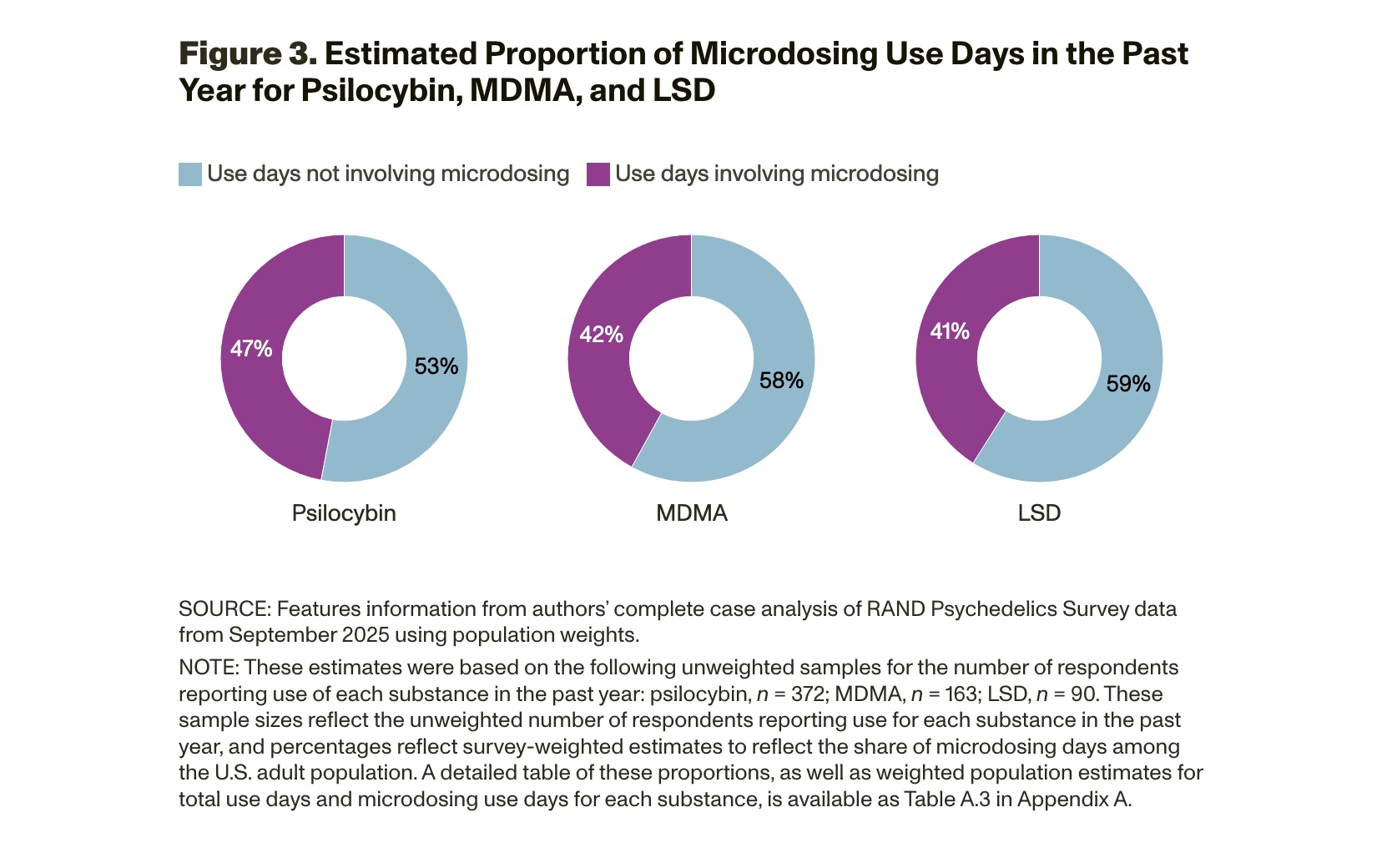

Figure 3 shows weighted estimates for the share of use days U.S. adults microdosed in the past year by substance for psilocybin, MDMA, and LSD. For psilocybin, we estimated approximately 216 million use days in the past year, of which approximately 102 million involved microdosing (47 percent). For MDMA, we estimated approximately 62.5 million use days in the past year, of which approximately 26.5 million involved microdosing (42 percent). For LSD, we estimated approximately 21 million use days in the past year, of which approximately 8.6 million involved microdosing (41 percent).

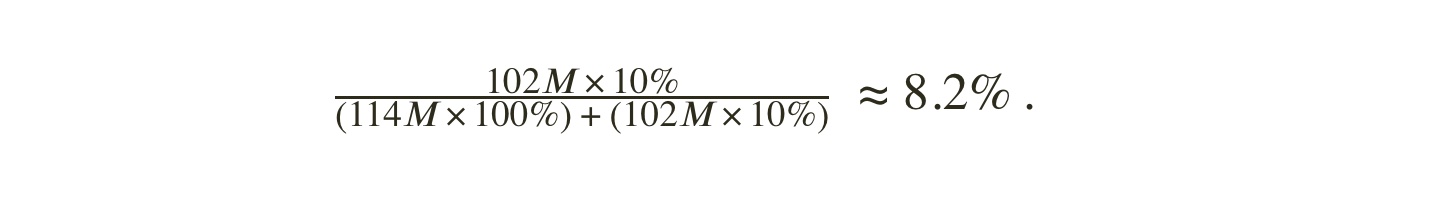

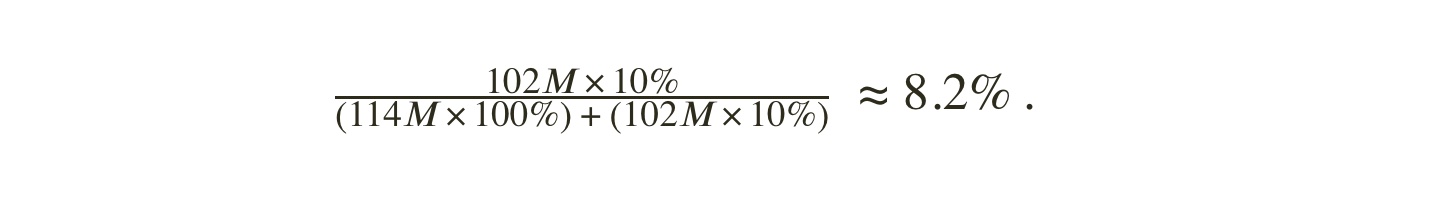

Although microdosing accounts for a noteworthy share of reported past-year use days, it accounts for a much smaller share of the total amount consumed of the substance in the past year. For example, if a typical microdose of psilocybin is 10 percent the size of a regular dose, and one assumes that very few people take a regular dose and a microdose on the same day, then less than 10 percent of the psilocybin consumed in the past year was in the form of microdosing:

Further research into amounts consumed in full doses and microdoses of these substances can aid in generating estimates for the total amount of these substances that are consumed nationwide. Future research could extend such calculations to include the total amount of spending on psychedelic substances attributable to microdoses.

– Michelle Priest, Beau Kilmer, Ben Senator, Claude Messan Setodji, Published courtesy of RAND.