An ambitious new study of genes in Asian populations is filling in big gaps in our understanding of human genetics, shedding light on the history of human migration and ultimately aiming to improve our ability to treat disease.

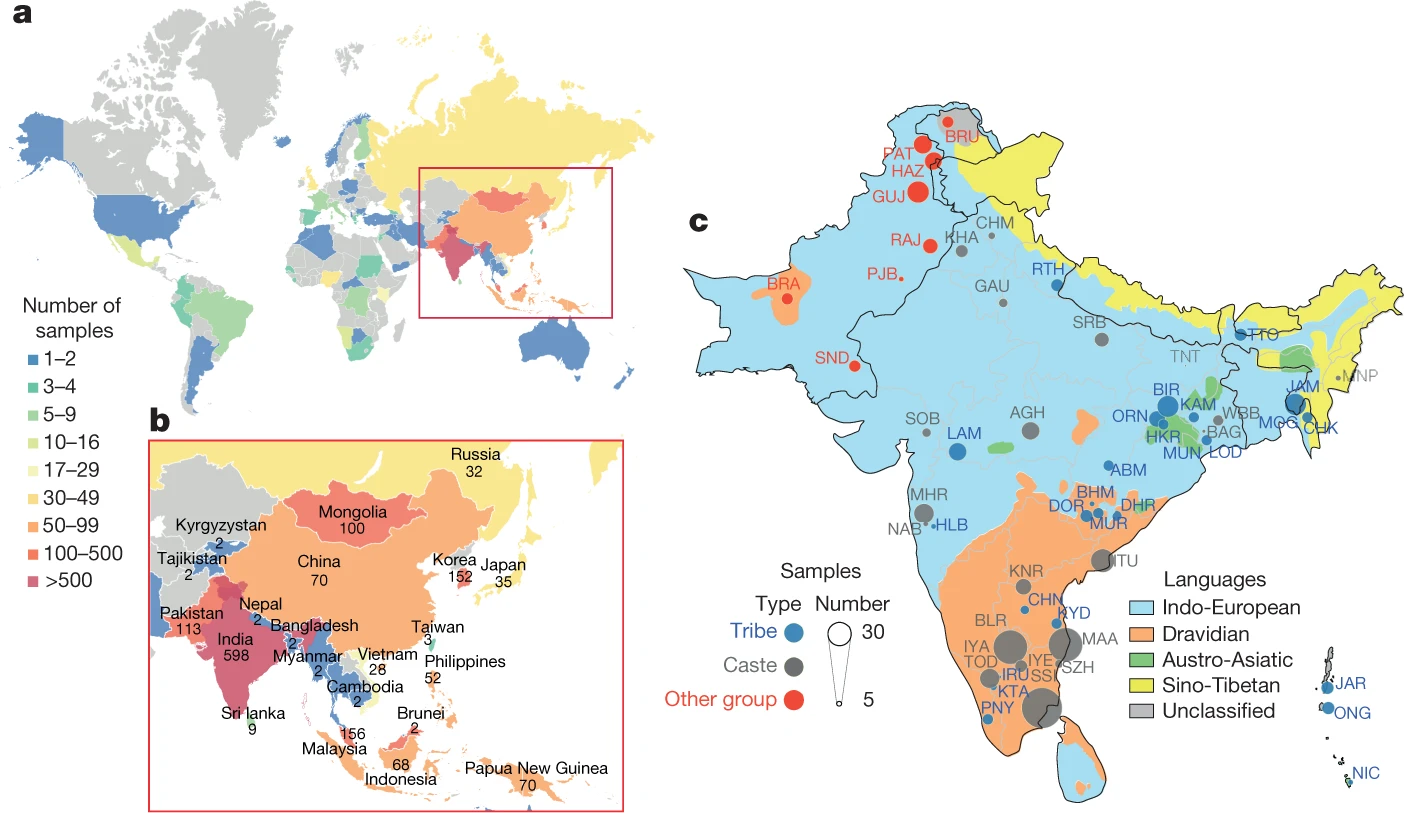

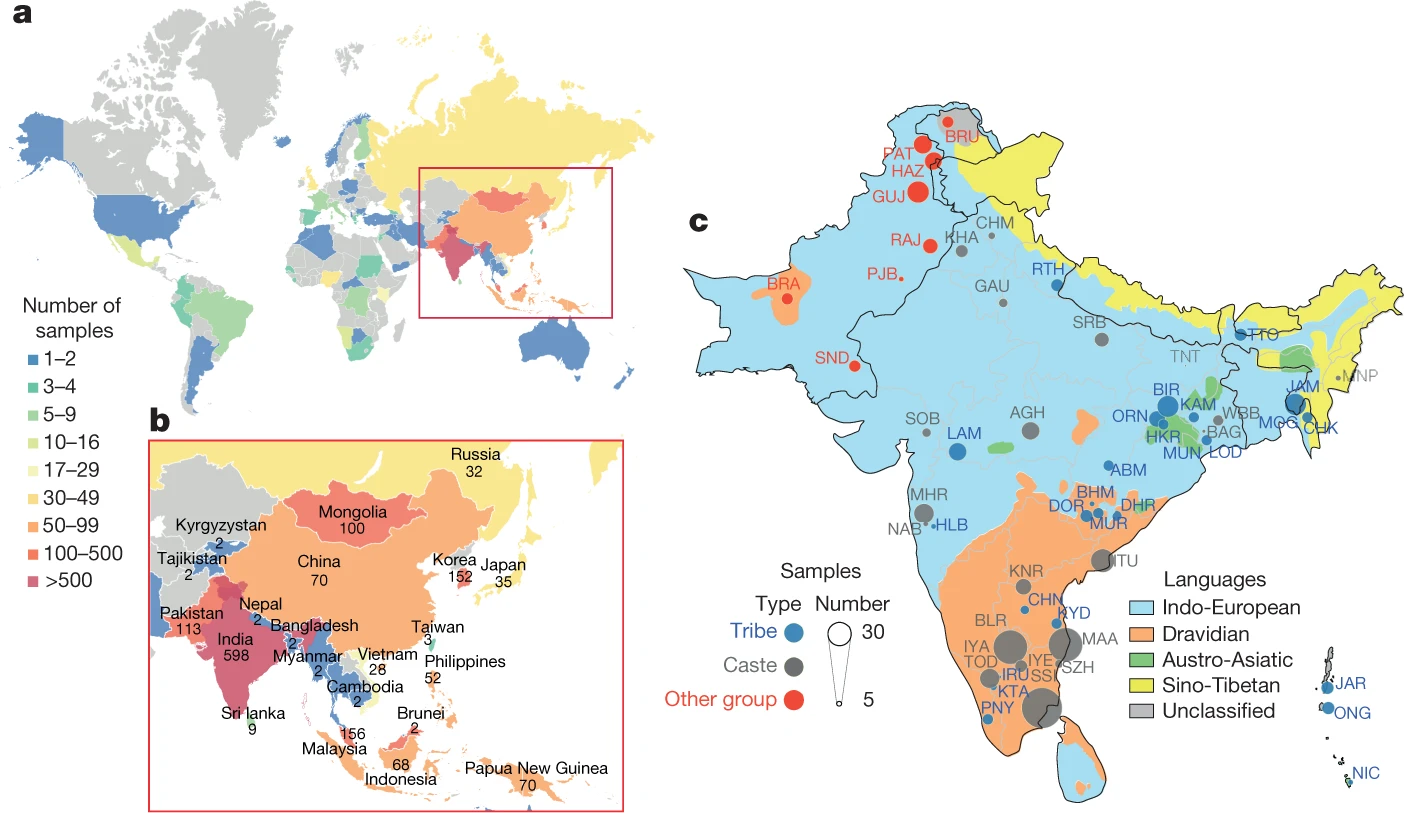

Researchers from dozens of institutions around the world, including the University of Virginia School of Medicine, are seeking to address the under-representation of Asian populations in genetic research. Working as the GenomeAsia100K Consortium, they have examined the genomes of 1,739 people from 219 different population groups in 64 countries across Asia. The ultimate goal, as the group’s name suggests, is to sequence the genomes of 100,000 people across Asia. This will produce a treasure trove of genetic information to help medical researchers and doctors better understand and treat genetic diseases, identify those at risk and even determine how patients will respond to drugs.

“Under-representation of Asian populations in genetic studies has meant that medical relevance for more than half of the human population is reduced,” said researcher Aakrosh Ratan, PhD, of UVA’s Department of Public Health Sciences and the Center for Public Health Genomics. “The main goal of the project is to increase the number of people included in these genetic studies, primarily to boost our knowledge about medical genetics but also to understand human migration and human origins.”

Natural Gene Mutations

There are natural gene mutations among and between different populations, Ratan explained. This partly explains why certain populations of different ancestry seem to have a greater risk of certain diseases. Creating detailed reference databases for Asian populations will be a big benefit for medical genetics for all human populations, but especially for efforts to understand rare diseases in Asia.

“For example, in our new paper, we talk about MODY, which refers to maturity-onset diabetes of the young. This is a rarer type of diabetes that usually develops before the age of 25, and often you do not require insulin,” Ratan said. “What we showed was that if doctors wanted to treat patients in India with the disease, they would greatly benefit from having information about genetic mutations found in Indian populations to identify the genetic differences that could be causing the disease. If you only look in databases that contain mutation data from European individuals, you are more likely to see false-positive results, and you will find it harder to pinpoint the exact gene causing the disease.”

Not only does the research shed light on the cause of diseases, but it will also help doctors better care for patients. For example, some groups may be more prone to an adverse reaction to a particular drug. Identifying the genes responsible could help doctors know which patients should not get that drug, or should not get that drug in certain doses.

“We also studied the genetic differences associated with an adverse reaction to several common drugs and were able to identify Asian populations that showed large variation in their response,” Ratan said. “These reference databases are vital to predict or understand why some drugs should not be dispensed in certain dosages to people of certain populations.”

Findings Published

Ratan and his collaborators in the GenomeAsia100K Consortium have published their early findings in Nature. They expect their research will continue for several years.

“I am excited that sequences from several Asian populations will become available as a result of this project,” Ratan noted. “It was my first time working in an international consortium, and it was an amazing learning experience.”