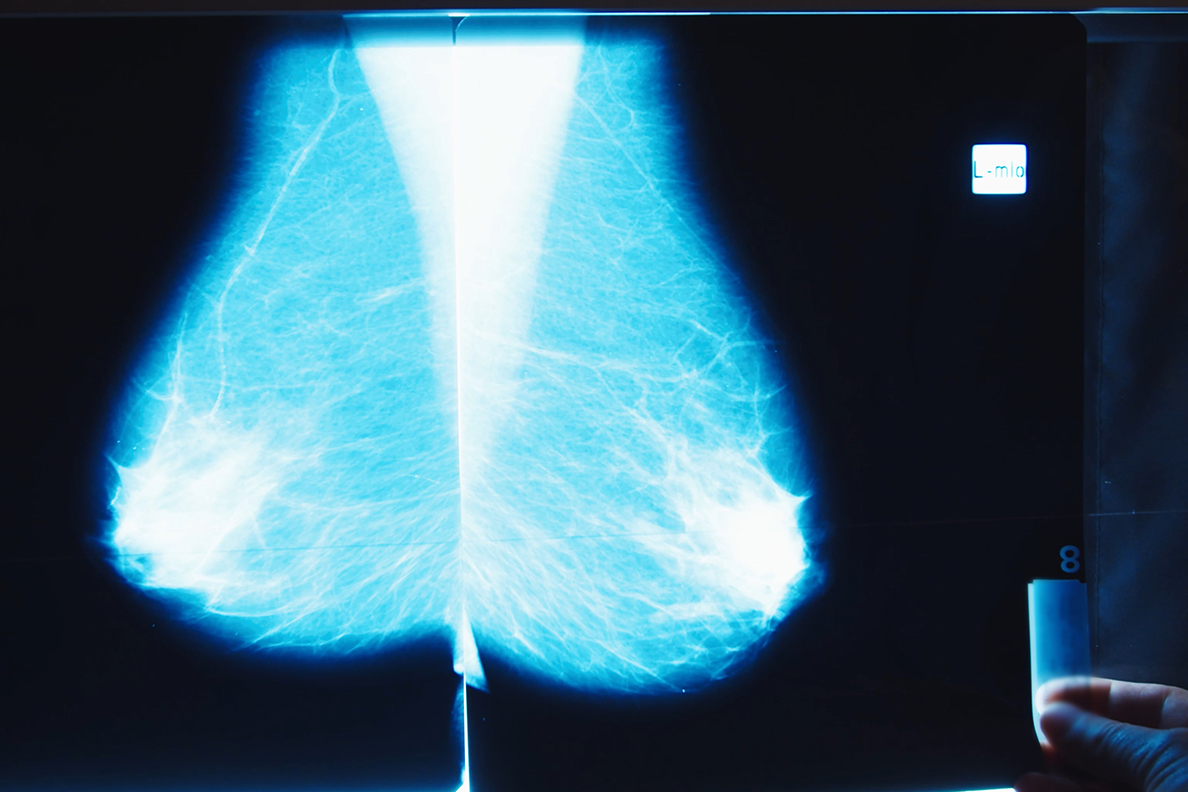

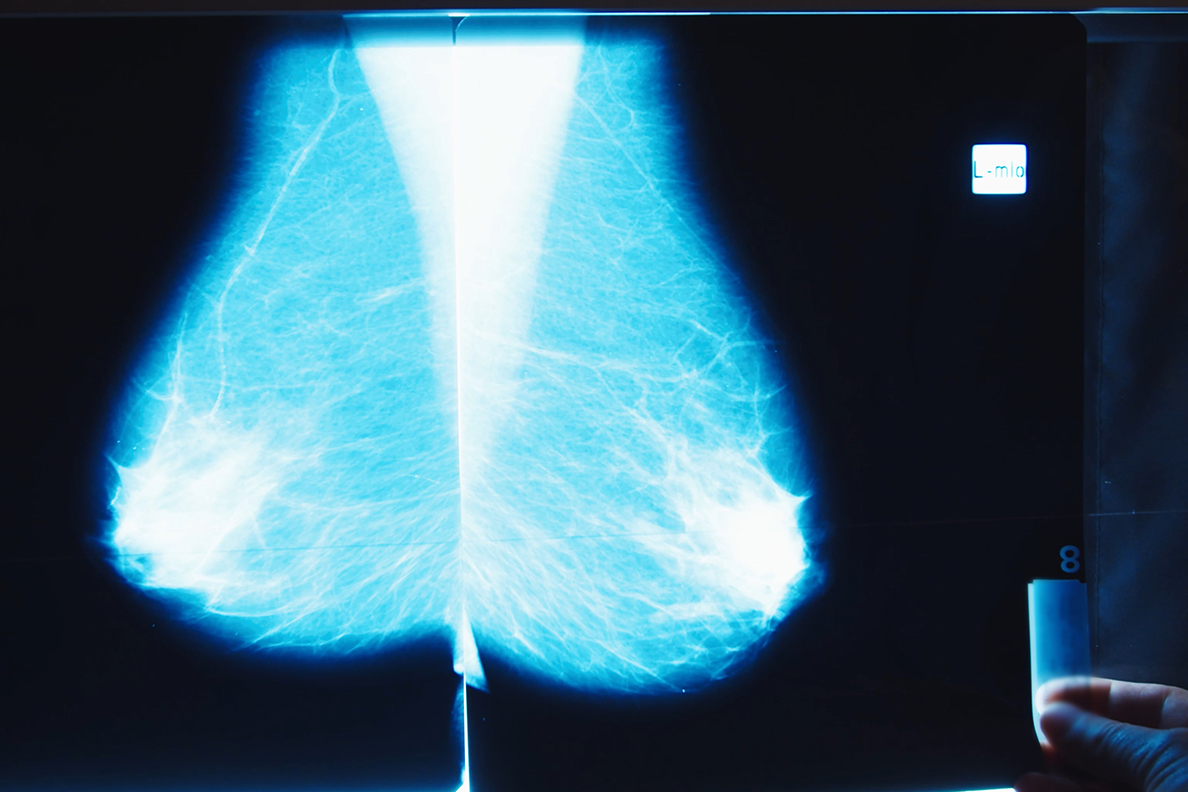

Breast cancer screening took a sizeable hit during the COVID-19 pandemic, suggests new research that showed that the number of screening mammograms completed in a large group of women living in Washington State plummeted by nearly half. Published today in JAMA Network Open, the study found the steepest drop-offs among women of color and those living in rural communities.

“Detecting breast cancer at an early stage dramatically increases the chances that treatment will be successful,” said lead study author Ofer Amram, an assistant professor in the Washington State University Elson S. Floyd College of Medicine whose research focuses on health inequities. “Our study findings suggest that health care providers need to double down on efforts to maintain prevention services and reach out to these underserved populations, who faced considerable health disparities even before the pandemic.”

The study was conducted by researchers at Washington State University Health Sciences Spokane in partnership with MultiCare, a not-for-profit health care system that encompasses 230 clinics and eight hospitals across Washington state. The research team used medical record data from MultiCare patients who had screening mammograms completed between April and December of 2019 and during the same months in 2020, after the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic in March 2020

The researchers saw the number of completed screening mammograms across Washington state fall from 55,678 in 2019 to 27,522 in 2020, a 49% decrease. When they analyzed the data by race, they saw a similar decrease in screening of 49% for white women but observed significantly larger decreases in non-white women. For example, breast cancer screening declined by 64% in Hispanic women and 61% in American Indian and Alaska Native women. The researchers also looked at geographical location and found that screening mammograms in rural women were reduced by almost 59%, whereas the number of mammograms completed in urban women fell by about 50%.

Additionally, the research team analyzed the data by insurance type and found that compared to women who were on commercial or government-run health insurance plans, screening reductions were greater in women using Medicaid or who self-paid for treatment, which Amram said are indicators of lower socioeconomic status.

“We know that the COVID-19 virus has had disproportionate impacts on certain populations, including racial and ethnic minority groups,” said Pablo Monsivais, senior author on the study and an associate professor in the WSU Elson S. Floyd College of Medicine. “What our study adds is that some of the secondary effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are also disproportionately impacting those populations, so it’s a double whammy.”

While previous studies have looked at missed cancer screening during the pandemic, Monsivais said this study is the first to examine racial and socioeconomic differences, specifically. The research team’s goal is to find ways to eliminate barriers to cancer screening, which would help reduce cancer-related health disparities. Their next step is to conduct a follow-up study to identify which social and economic factors interfered with access to cancer screening during the pandemic. In addition to breast cancer, that study will also look at missed colon cancer and lung cancer screening in both women and men.

Factors that may have played a role in reduced cancer screening include job loss, loss of employer-provided health insurance, and caregiver stress due to school- or daycare closures or other circumstances. Fear of contracting COVID-19 may have also played into this, said study co-author Jeanne Robison, an oncology nurse practitioner and lead researcher on this project with MultiCare Cancer and Blood Specialty Centers in Spokane, Washington.

“One of the things we have seen this past year is that women who were pretty good about keeping up with screening remained fearful about going in even after health care facilities had opened back up for routine screening,” Robison said. “I’ve had to talk some of my patients into coming in, however, because even when protocols were in place to safely offer breast cancer screening, there remained a perceived risk.”

A drop in primary care visits during the pandemic may have also been a factor, she said, as primary care providers often play a key role in reminding women of the timing and importance of breast cancer screening. And although increased access to virtual visits may have mitigated this drop, there may have been barriers to virtual care delivery that disproportionally impacted certain groups of people, which the researchers’ follow-up study will help determine.