Outcome indicators make quality of life after childhood cancer measurable

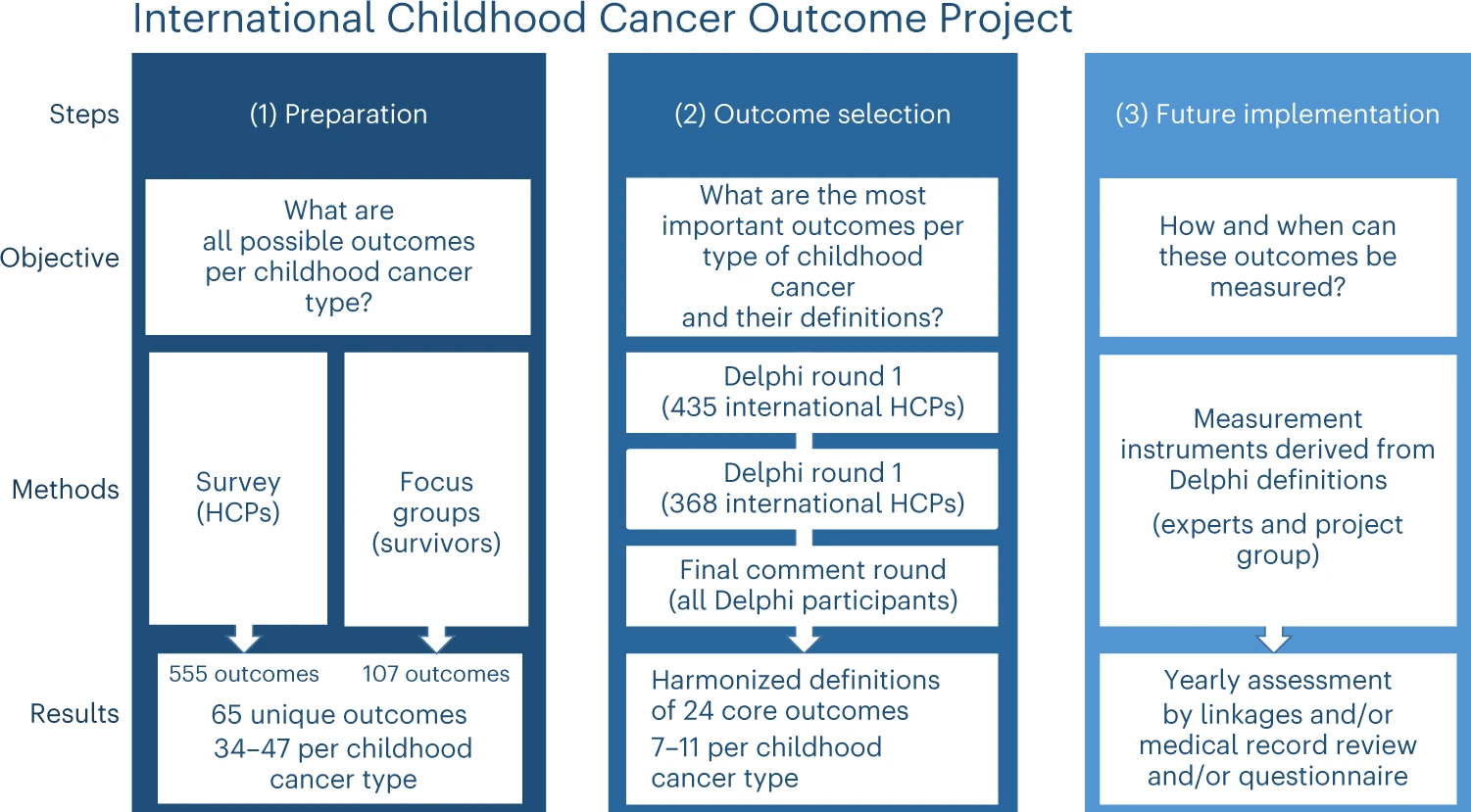

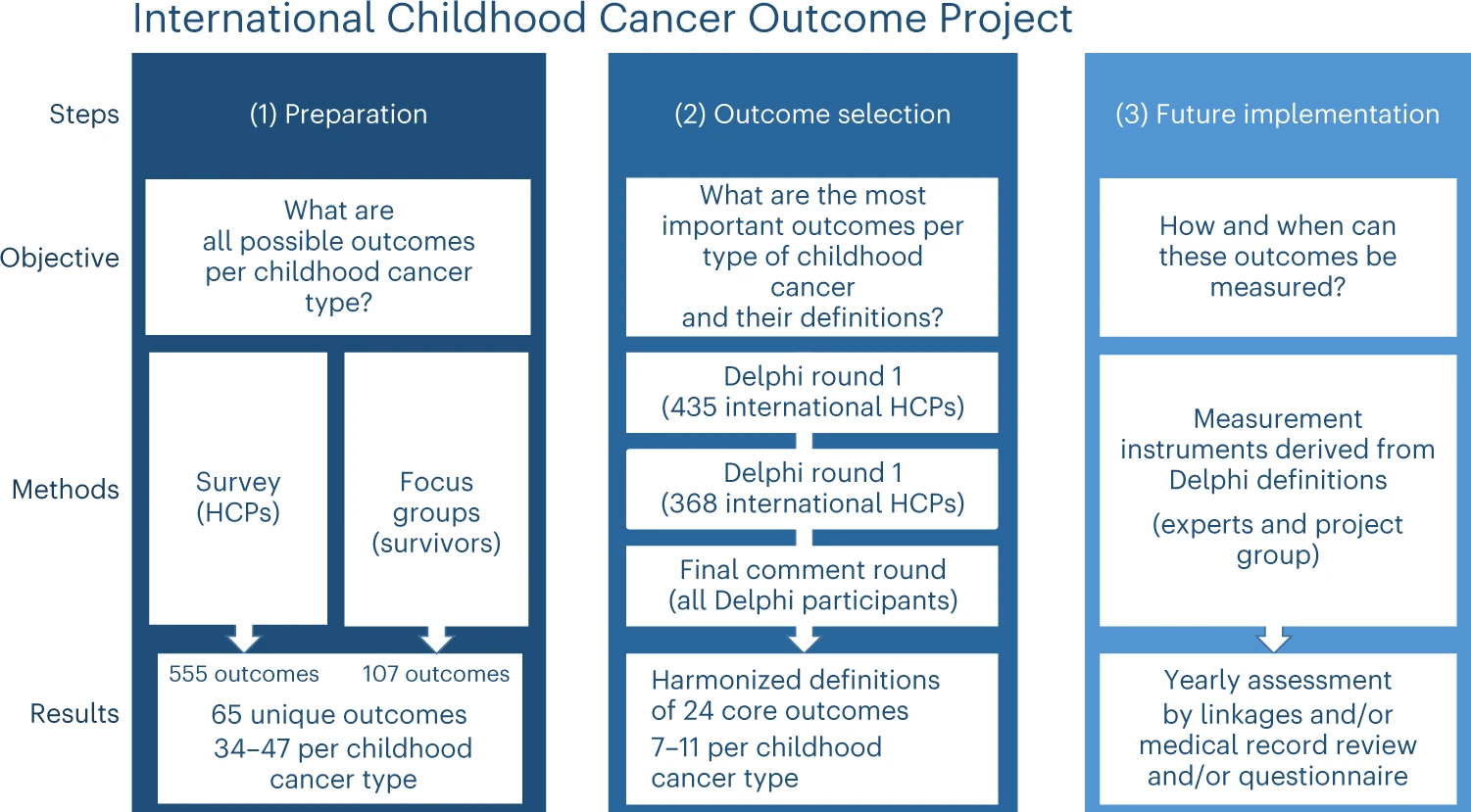

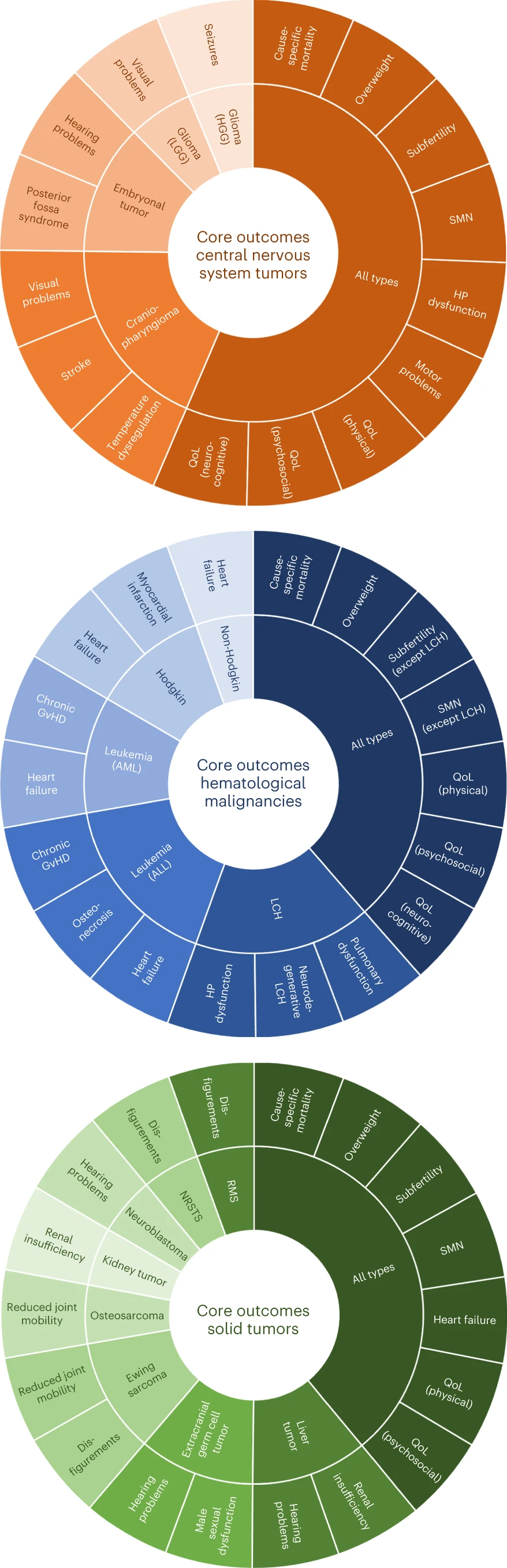

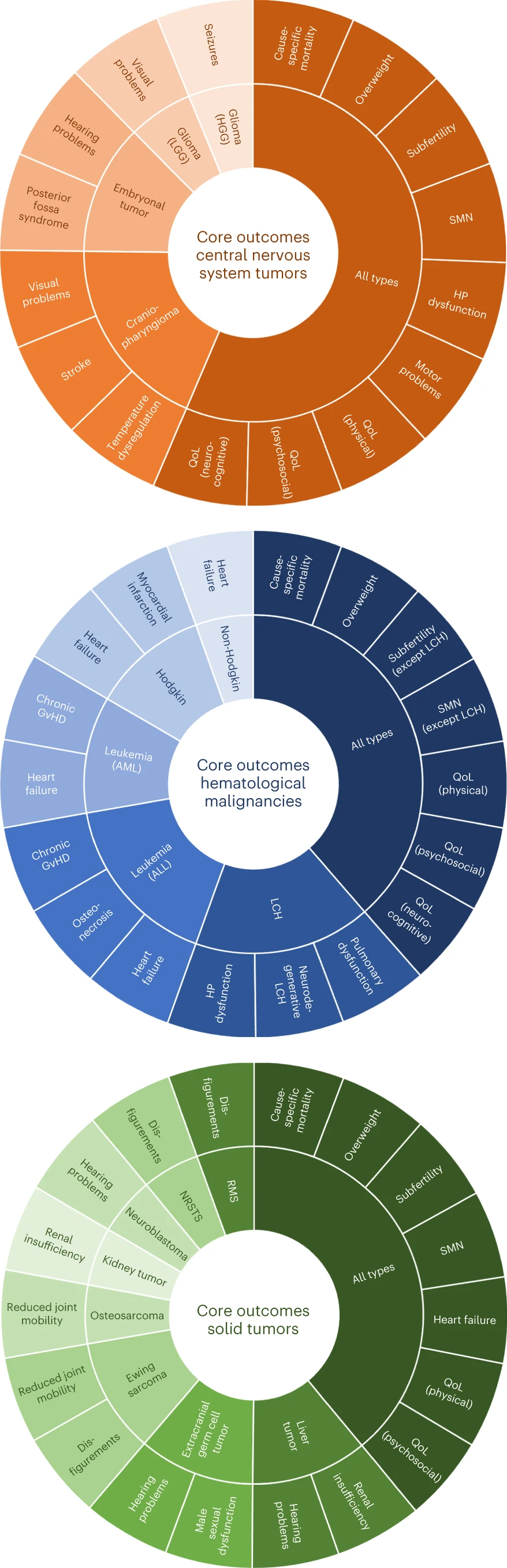

A new measurement tool helps analyzing the survival rate of children with cancer, but also the quality of survival. Researchers at the Princess Máxima Center for Pediatric Oncology have worked with patients and survivors to develop a set of outcome indicators that measure health issues. By making the balance between survival and quality of life measurable, the outcome indicators help improve care for children with cancer.

There are many types of childhood cancer, and the consequences for later life can vary enormously. Some children or adults after surviving childhood cancer experience daily consequences of the disease or treatment, on the physical and psychosocial as well as the neurocognitive level. Others have relatively few late effects and can live their lives like anyone else. The more relevant data is available, the more effective treatments with less adverse effects can become. Researchers faced the question: how do you determine the quality of survival after childhood cancer?

International consensus

The initiative for the outcome indicators project was taken by the Princess Máxima Center together with St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in the United States. Researchers surveyed more than 450 experts in pediatric oncology worldwide, as well as people who themselves had cancer as children. Consensus was reached on 24 clinically relevant outcomes for 18 types of childhood cancer. The results of the project were published on Thursday 15 June in the leading journal Nature Medicine.

Quality of survival

‘Especially now that pediatric cancer survival is improving significantly, attention to the quality of survival is very important,’ says Rebecca van Kalsbeek, PhD student in the Kremer group at the Princess Máxima Center. ‘Together, we selected physical, psychosocial and neurocognitive outcomes. Certain outcomes emerged in almost all types of childhood cancer: heart failure, development of a second tumor, fertility and psychosocial quality of life. There is now good international consensus on the outcomes that determine quality of survival and say something about the quality of care we provide.’

Highest level

Prof. dr. Rob Pieters, medical director of the Princess Máxima Center, says: ‘With the development of outcome indicators, we want to account for quality of care at the highest level as the largest pediatric oncology center in Europe. What are our outcomes of care and treatment like? How can we further improve our care during and after cancer treatment? What is important for patients in later life? Using outcome indicators, we now make the quality of our care and the health of the cured child clearly measurable and comparable with other hospitals. That’s part of the mission of the Máxima Center, to cure all children with cancer with optimal quality of life.’

Global collaboration

When outcome indicators are systematically tracked and evaluated, it becomes possible to improve evidence-based care during and after childhood cancer. Prof. dr. Leontien Kremer, principal investigator of late effects at the Princess Máxima Center, says: ‘Because pediatric tumors are relatively rare, it is very important to collaborate internationally. The strength of the outcome indicators project is the collaboration between people from different backgrounds. Survivors and pediatric oncologists, nursing specialists and (neuro)psychologists, among others, contributed their own perspectives, and together we agreed on what outcomes are important for children and survivors.’