Rarely is there such precise historical information about the origin of an infectious disease as in the case of syphilis : in 1493, during the siege of the city of Naples by French troops. From there, it spread rapidly throughout Europe and Asia, causing one of the most devastating epidemics for humanity for several centuries, which ended when, thanks to penicillin, it could be treated properly in the 20th century.

The coincidence in time with the return of Columbus’s first expedition to the Americas and some indirect chronicles led to the hypothesis that the origin of this disease occurred on the American continent , and was taken to Europe on Columbus’ ships. Research recently published in Nature , based on skeletons from an ancient archaeological site located on the coast of southern Brazil, may clarify this controversy.

Ancient genomes and modern phylogenies

Together with researchers from the universities of Zurich, Basel, Vienna, ETH Zurich, Autonoma de Barcelona and also the University of São Paulo (USP) , we present the analysis of a genome of the bacterium Treponema pallidum obtained from 2,000-year-old samples from a tomb indigenous people (sambaqui) from the Jabuticabeira II archaeological site , located in the region of the municipality of Laguna, on the coast of Santa Catarina.

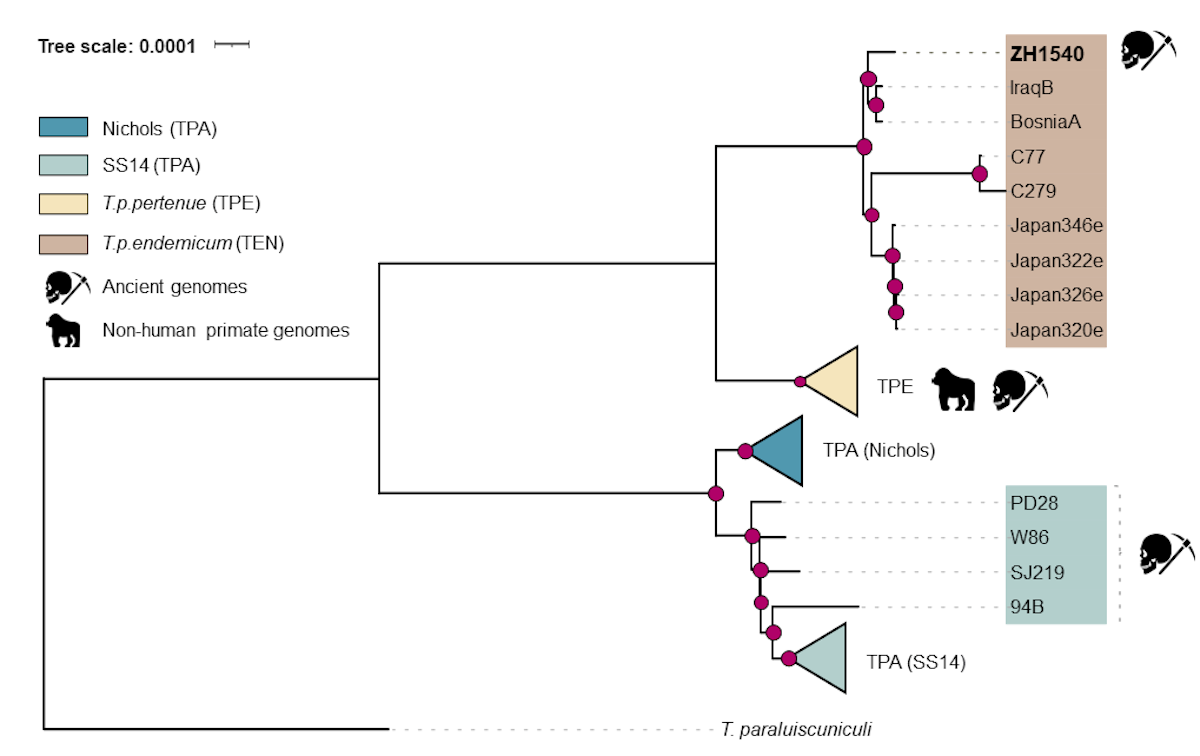

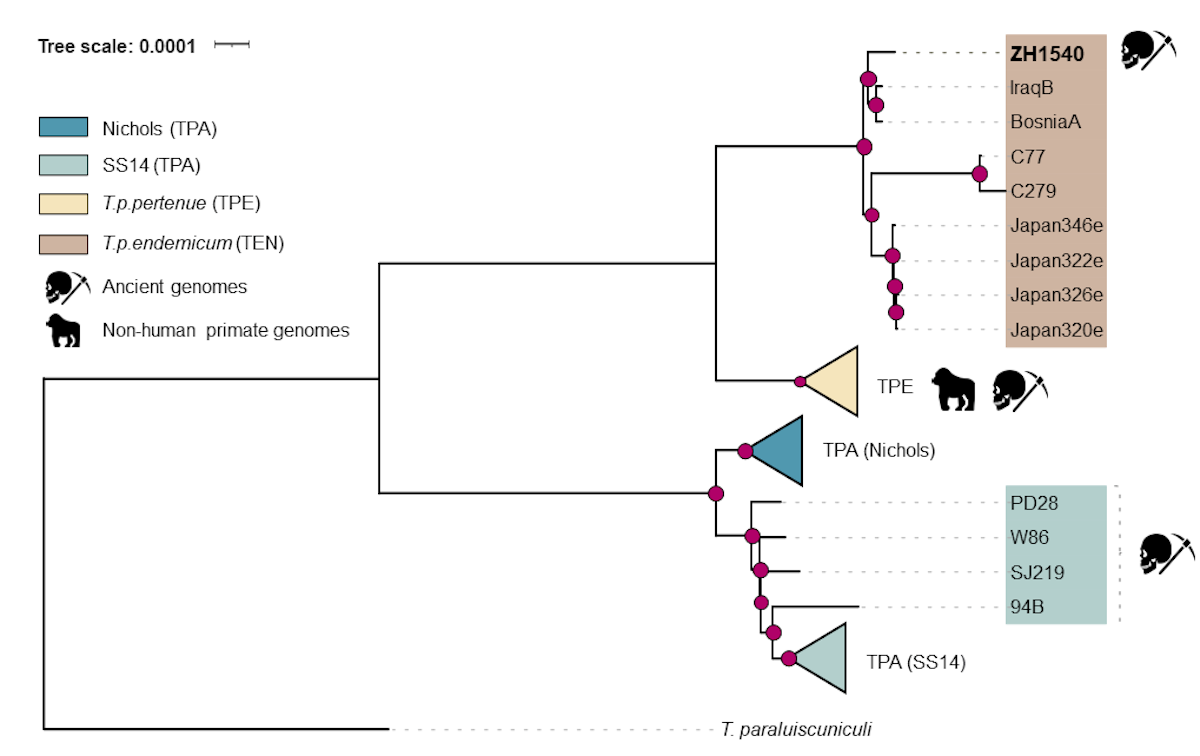

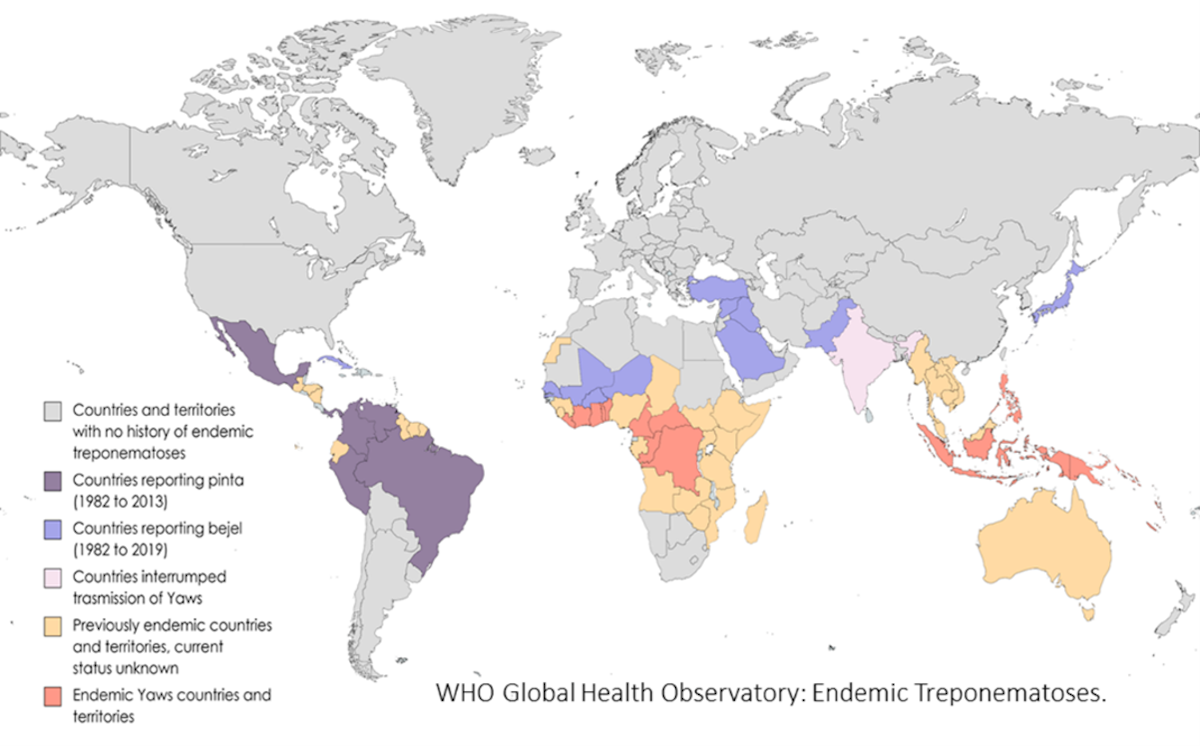

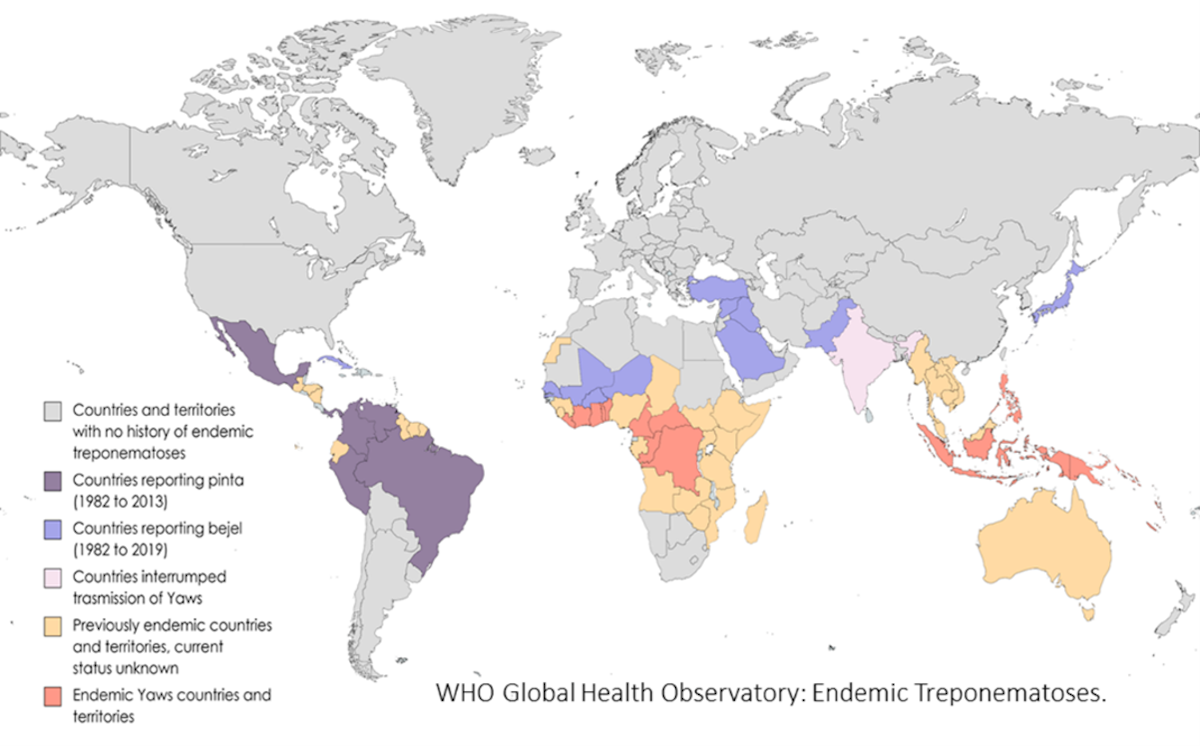

This genome, of high quality for such an ancient genome, clusters with the modern genomes of T. pallidum endemicum (TEN), the strain that causes bejel , a chronic mucosal infection currently restricted to hot, arid areas of the planet, and not previously described in the Americas. This strain, as well as T. pallidum pertenue (TPE), which causes another tropical treponemal infection called yaws, is closely related to the strain that causes syphilis, T. pallidum pallidum (TPA).

The sudden appearance of syphilis in the late 15th century led to the proposal of its American origin, known as the Columbian hypothesis . But that was not the only proposal.

More popular alternatives are the pre-Columbian hypothesis, according to which all treponematoses have accompanied humanity since its origins, with different manifestations as they spread across different regions. There is also the unitary hypothesis, a slight variant of the pre-Columbian hypothesis, according to which the emergence of different treponematoses corresponds to adaptations of the same bacterium to different ecological conditions.

Until now, the problem with these hypotheses has been the lack of concrete data to refute or validate them, as typical skin lesions leave no trace after corpses decompose and bone lesions are common to different infections. This led to a search for biological traces of the bacteria in ancient human remains.

Using the same techniques used for the remains of Neanderthals Although it has not yet been possible to recover the bacteria, thanks to the same sequencing techniques applied to the remains of Neanderthals or Denisovans , some complete genomes of T. pallidum have been obtained.

Most of these genomes come from central and northern Europe and some from Mexico , but their dating does not allow us to rule out the possibility that they date from after Columbus’s return. These genomes cluster with the TPA and TPE lineages, leaving open the question of the origin of syphilis.

The new genome expands the geographic and temporal range of T. pallidum distribution to the Americas in pre-Columbian times and also before the Viking expeditions that reached the coasts of North America. Our analysis clearly places it in the TEN lineage. In fact, its short genetic distance from the few available genomes of this lineage is surprising, a detail that confirms its attribution to this lineage.

The origin of these remains is also surprising. Currently, bejel is found in hot and arid regions, climatically and ecologically very different from the Atlantic margins of subtropical Brazil.

Did Columbus play an important role in the spread of syphilis?

What does the new genome tell us about the origins of syphilis? Little and a lot at the same time. His participation in TEN implies that treponemas were present in the Americas before Columbus arrived, but not that one of them necessarily caused syphilis.

All of the above hypotheses receive some empirical reinforcement. The new dating slightly pushes back the origin of TPA to around 1,000 BC, but its accuracy may improve as new ancient genomes are incorporated into the analyses.

The study of the genomes of this bacterium revealed the great plasticity of T. pallidum to exchange genes. In particular, the TPA lineage has received several contributions from other lineages, TPE and TEN.

It is possible that one of these cases of horizontal gene transfer incorporated into a strain of treponema the ability to be more easily transmitted sexually and cause previously unknown symptoms. Did this happen in Europe after Columbus returned? This is a fascinating possibility that we want to explore further.