A new study from scientists at Cincinnati Children’s suggests there may be a way to further protect transplanted hearts from rejection by preparing the donor organ and the recipient with an anti-inflammatory antibody treatment before surgery occurs.

The findings, published online in PNAS, focus on blocking an innate immune response that normally occurs in response to microbial infections. The same response has been shown to drive dangerous inflammation in transplanted hearts.

In the new study – in mice — transplanted hearts functioned for longer periods when the organ recipients also received the novel antibody treatment. Now the first of a complex series of steps has begun to determine whether a similar approach can be safely performed for human heart transplants.

“The anti-rejection regimens currently in use are broad immunosuppressive agents that make the patients susceptible to infections. By using specific antibodies, we think we can just block the inflammation that leads to rejection but leave anti-microbial immunity intact,” says corresponding author Chandrashekhar Pasare, DVM, PhD, director of the Division of Immunobiology at Cincinnati Children’s.

Making memory T cells a bit more forgetful

The research team, which included first author Irene Saha, PhD, a research fellow in the Pasare Lab, and several colleagues at Cincinnati Children’s, zeroed in on how dendritic cells from the donor organ trigger an inflammatory response in the recipient’s body.

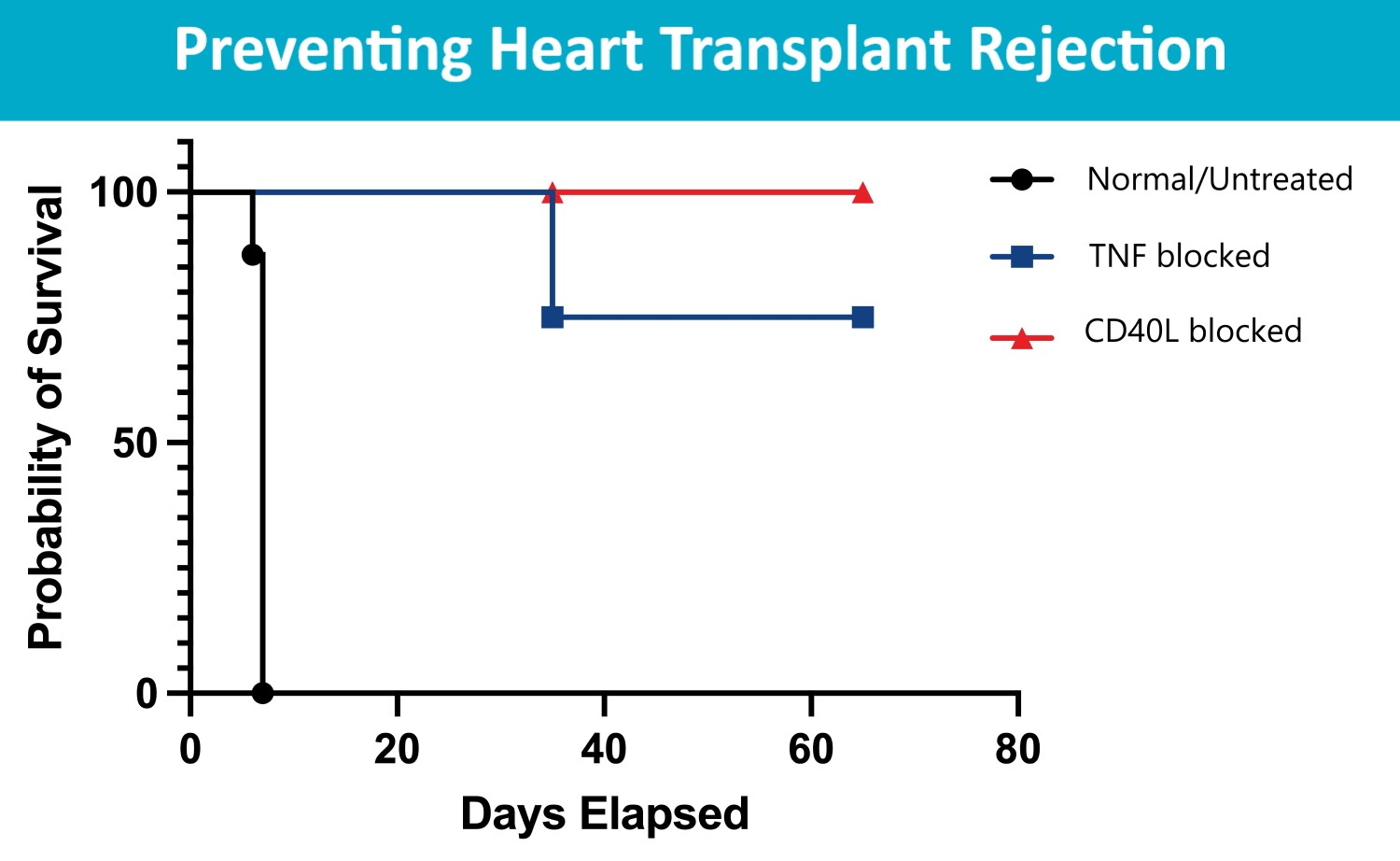

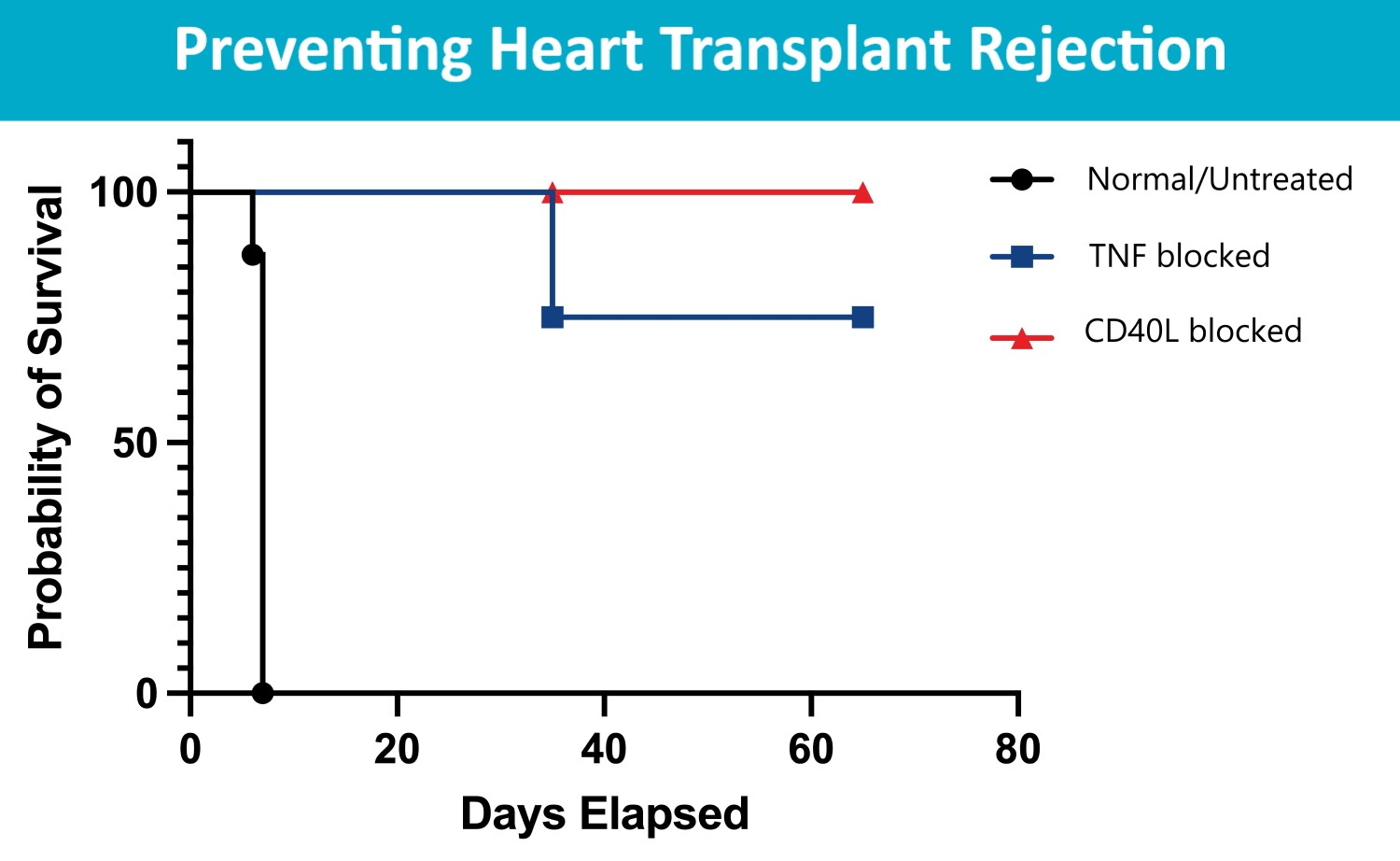

Specifically, the team found that memory CD4 T cells in the recipient activated donor dendritic cells through signals delivered by the proteins CD40L and TNFα. When this signaling pathway was blocked with gene editing techniques, the results included dampened inflammation and prolonged survival of transplanted hearts.

In the study, untreated mice rejected the donated heart within a week. But in mice that were gene edited to lack receptors for CD40L and TNFα, strong heart function persisted through day 66, when the experiment was terminated.

“We have been working on this for almost a decade,” Pasare says. “The major reason we figured out this pathway is because we focused on understanding how memory T cells in the recipient with potential reactivity to donor specific antigens induce innate inflammation. The rest of the field has focused on other concepts such as ischemia reperfusion injury, ligands from dead cells, and innate immune receptors, none of which seem to really lead to transplant rejection.”

Pasare continues: “The key to preventing organ rejection is to take away the ability of recipient’s memory T cells to initiate inflammation when they recognize donor antigens in dendritic cells. While T cell memory is critical to fight infections, the innate inflammation initiated by memory T cells is detrimental to the survival of transplanted organs.”

Next steps

The co-authors believe the process they used to protect hearts from rejection may also apply to other forms of organ transplantation.

However, the gene editing performed with the mice would not be considered safe for humans. So now the research team is evaluating other ways to disrupt the inflammatory response.

“Using blocking antibodies against CD40 could be a good approach. Another option would be to create biologics or compounds that specifically target the TNF receptor superfamily in humans,” Pasare says. “I think this is a very exciting area for future drug development.”