Pancreatic cancer is one of the deadliest cancers worldwide, with a five-year survival rate of 13%. This poor prognosis stems from both late detection and the cancer’s notorious capacity to adapt and resist therapy. Now, a study led by researchers at the University of Verona, University of Glasgow, and the Botton-Champalimaud Pancreatic Cancer Centre uncovers a hidden driver of this adaptability: extrachromosomal DNA (ecDNA).

A New Player in Pancreatic Cancer

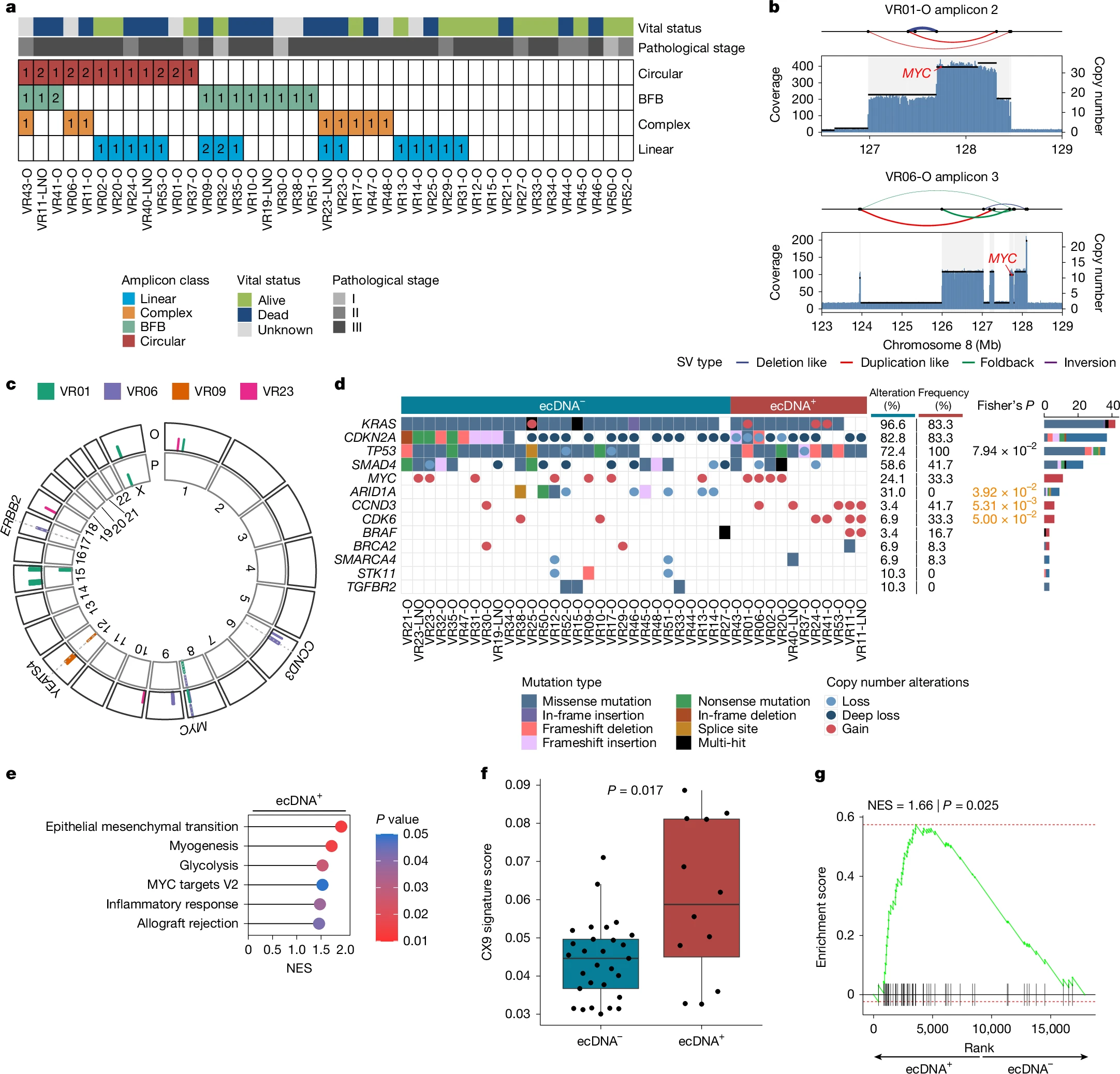

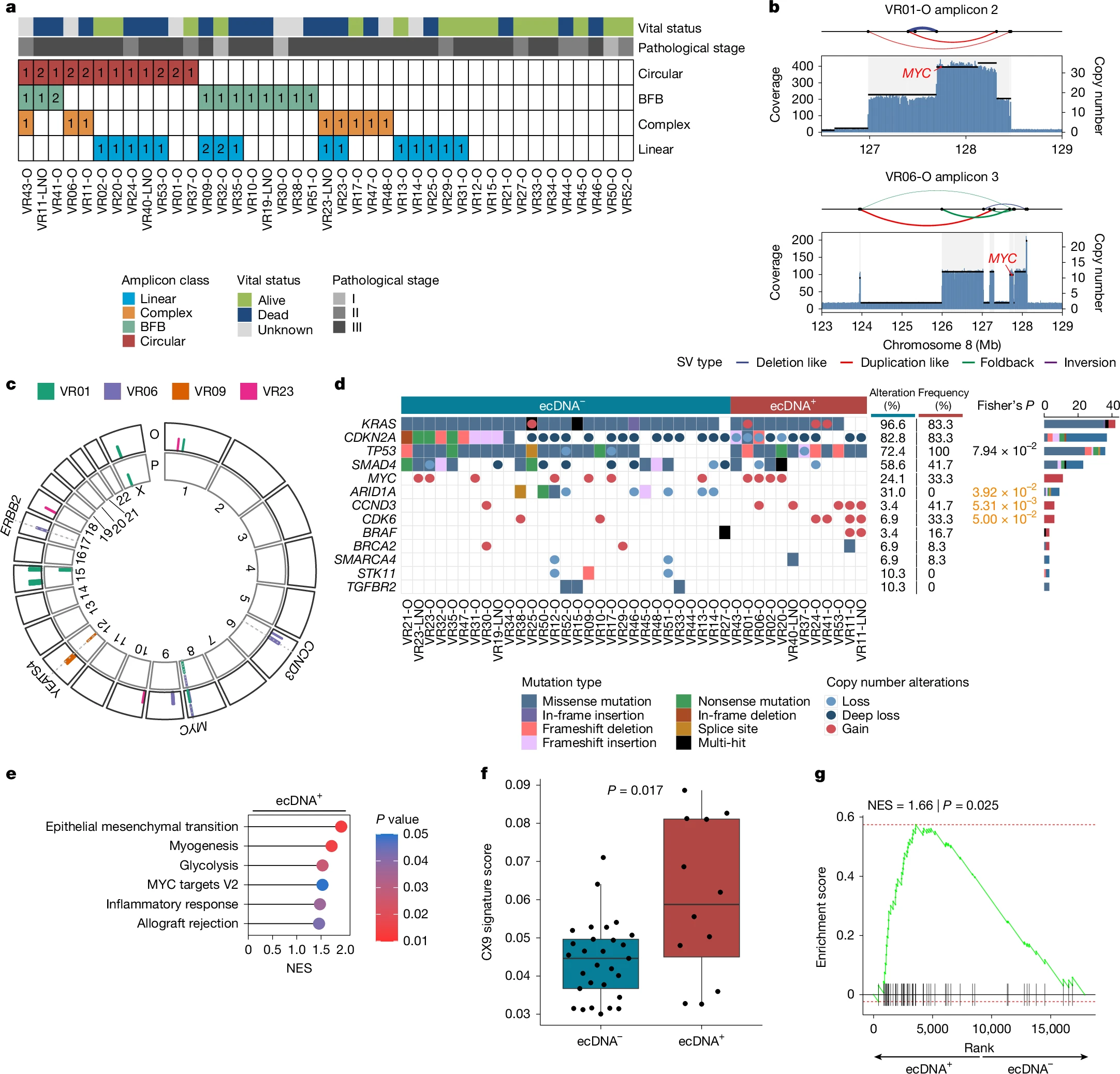

The team found that some pancreatic cancer cells gain a major survival edge by carrying copies of critical cancer genes—such as MYC—on circular pieces of DNA that exist outside chromosomes, the structures that house most of our genetic material. Known as ecDNA, these genetic rings float freely in the cell nucleus, enabling tumour cells to swiftly ramp up gene expression, change their shape, and survive in otherwise hostile environments.

“Pancreatic cancer is often called a silent killer because it’s hard to detect until it’s too late”, says Peter Bailey, co-corresponding author and Director of Translational Research at the Botton-Champalimaud Pancreatic Cancer Centre. “We know that part of its lethality arises from the ability of tumour cells to ‘shape shift’ under stress. Our study shows that ecDNA forms a big part of that story”.

The researchers discovered ecDNA to be surprisingly common in pancreatic tumours, particularly for oncogenes like MYC, which drives cancer growth and metabolism. “We saw far more variability in MYC copy number when MYC was on ecDNA”, explains Elena Fiorini, co-first author and senior postdoc. “Some cells carried dozens—or even hundreds—of extra MYC copies, giving them a large growth advantage under certain conditions”.

“It’s effectively a ‘bet-hedging’ strategy”, adds Daniel Schreyer, co-first author and former PhD student of the University of Glasgow. “You get pockets of cells that carry very high MYC levels, which is beneficial under certain conditions, and others with fewer copies, which might do better in another environment—all within the same tumour”.

Such flexibility underscores the profound intratumour heterogeneity characteristic of pancreatic cancer, where myriad sub-populations coexist and respond differently to treatment. Targeting one subset often fails against another, fueling resistance.

A key advantage of this study is that the organoids—mini-3D replicas of pancreatic tumours grown in the lab—were derived directly from patients with early-stage disease. These organoids preserve much of the genetic make-up of the original tumour, making them excellent testbeds for studying cancer. Unlike methods that artificially introduce ecDNA, these lab models reflect genuine ecDNA variants found in real tumours.

“This approach offers real-world insight into how dynamic and disordered a tumour can be”, says Fiorini. “We see firsthand that even when two patients both have MYC on ecDNA, the structure of that circular DNA can differ substantially—leading to big variations in MYC expression”.

Plasticity in Action: Organoids in the Lab

To see how ecDNA drives adaptation, the researchers grew patient-derived organoids and removed vital growth signals—such as WNT factors—and then observed how these organoids responded to the stress.

“We found that organoids bearing MYC on extrachromosomal DNA could shift their dependency on WNT”, explains Antonia Malinova, co-first author and a former PhD student at the University of Verona. “Essentially, cells with high levels of ecDNA became more self-sufficient, no longer needing those external signals to survive”.

The study also revealed a clear link between high MYC levels and changes in tumour cell shape and behaviour. When MYC ecDNA levels soared, cells morphed into more aggressive, solid structures—losing their more organised, gland-like architecture.

“What’s remarkable”, says co-corresponding author Vincenzo Corbo from the University of Verona, “is how rapidly these ecDNA-based copies can appear or disappear depending on the environment. If the cancer is under pressure—say, lacking key growth factors—cells with ecDNA can crank up MYC expression to survive. But if that pressure lifts, they can lose some of these extra DNA circles to avoid the downsides of carrying too many copies”.

Indeed, expressing MYC at high levels can trigger DNA damage, forcing cancer cells to carefully balance the costs and benefits of ecDNA retention. “That was unexpected”, says Corbo. “It challenges the assumption that more MYC is always better for a cancer cell—there’s a real fitness cost to maintaining such high levels”.

ecDNA as a Therapeutic Target?

Although extrachromosomal DNA only appears in about 15% of patient samples in this study, that subset might be particularly aggressive or prone to therapy resistance. As a result, detecting or disrupting ecDNA could open new therapeutic windows.

“We might imagine a strategy that exploits the vulnerabilities introduced by ecDNA”, notes Corbo. “Perhaps pushing cancer cells to dial MYC up to a point where they can’t handle the DNA damage, or blocking the molecular circuits that maintain these DNA rings so cells lose them altogether”.

However, the authors caution that such ideas remain early-stage. “ecDNA is a double-edged sword—helpful for quick adaptation but costly to maintain”, says Corbo. “The challenge is to tip that balance in favour of the patient”.

Crucially, this work broadens our understanding of genomic plasticity—challenging the notion that the genome is always “fixed”. “We knew the tumour’s surroundings could drive changes, but not that WNT signalling could so directly rewrite DNA”, Bailey adds. “We assumed we’d see mostly epigenetic shifts, so seeing this level of genomic re-engineering was definitely a surprise”.

And with pancreatic cancer cases projected to rise in the coming years, insights into ecDNA’s role could guide future strategies to intercept or exploit this genetic feature—potentially making tumours more vulnerable to treatment.