People with psychopathic tendencies are slightly more likely to be a company boss, but a new study finds men are allowed a pass for those inclinations while women are punished.

The study, published online today in the Journal of Applied Psychology, finds concern over psychopathic tendencies in bosses may be overblown, but that gender can function to obscure the real effects.

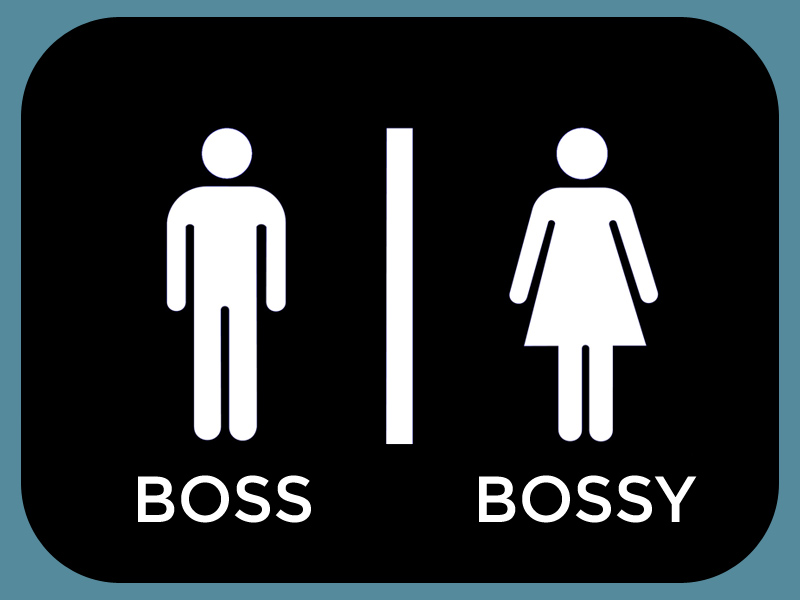

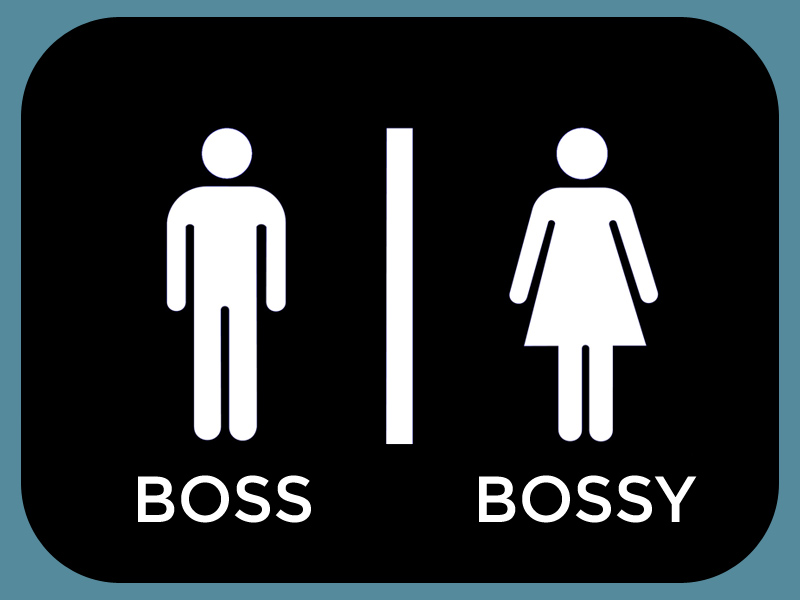

“Aggressive behavior is seen as more prototypical of men, and so people allow more displays of that kind of behavior without social sanctions,” said Dr. Peter Harms, associate professor of management at The University of Alabama. “If women behave counter to gender norms, it seems like they get punished for it more readily.”

Karen Landay, lead author on the paper and doctoral student in management at UA, and co-author Dr. Marcus Credé, assistant professor of psychology at Iowa State University, are part of a review of previous studies along with new research.

A psychopathic personality has three characteristics, including boldness in asserting dominance over others, being impulsive without inhibition, and a lack of empathy. There have been several studies showing people with some level of those traits are over represented as organizational bosses.

For this study, the researchers set out to determine whether there are optimal levels of psychopathy for success as a leader and if gender made a difference. They found tendencies help slightly when a person is rising through management ranks, but bosses behaving this way are less effective as leaders.

“Overall, although there is no positive or negative relation to a company’s bottom line when psychopathic tendencies are present in organizational leaders, their subordinates will still hate them,” Harms said. “So we can probably assume they behave in a manner that is noxious and whatever threats they make to ‘motivate’ workers don’t really pay off.”

When the data is broken down by gender, though, it shows that psychopathic traits in men help them emerge as leaders and be seen as effective, but these same tendencies are seen as a negative in women.

“The existence of this double standard is certainly disheartening,” Landay said. “I can imagine that women seeking corporate leadership positions getting told that they should emulate successful male leaders who display psychopathic tendencies. But these aspiring female leaders may then be unpleasantly surprised to find that their own outcomes are not nearly as positive.”

This double standard could be a fruitful area for future research, but, for Harms, the implications for organizations are clear.

“We should be more aware of and less tolerant of bad behavior in men,” he said. “It is not OK to lie, cheat, steal and hurt others whether it is in the pursuit of personal ambition, organizational demands or just for fun.”