Mount Sinai researchers have received $2.9 million from the National Institutes of Health to study whether a first-of-its-kind brain implant can improve the ability of severely paralyzed patients to communicate. The grant is part of a $10 million award that will fund a national multi-center clinical trial that will be first to implant this device and study it in United States patients. Its findings could lead to a new therapy for this population, giving them independence to perform basic, important tasks and improve their quality of life.

“This will be an historic clinical trial that has the potential to change what is possible for people living with severe paralysis,” says David Putrino, PhD, PT, Director of Rehabilitation Innovation for the Mount Sinai Health System and a Principal Investigator of the study. “We are excited that Mount Sinai’s Department of Rehabilitation and Human Performance and Department of Neurosurgery will be working closely together to bring this highly innovative research to our Health System.”

The Stentrode device, developed by Synchron, Inc., is a small brain-computer interface implanted through blood vessels in the brain. As part of the multi-site research effort, Mount Sinai will study how implantation of this device in six patients with severe paralysis, caused by stroke, injury, or late-stage amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, a neurodegenerative disease that causes severe paralysis of the entire body), can significantly improve quality of life, daily function, and ultimately health outcomes.

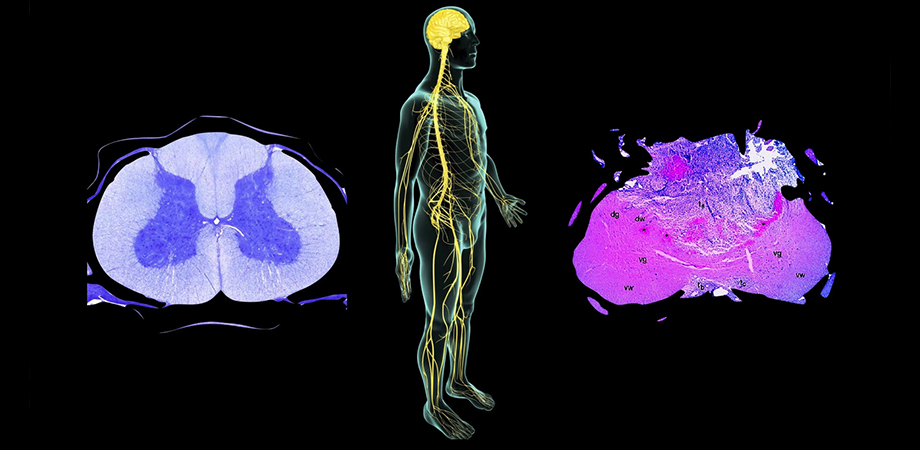

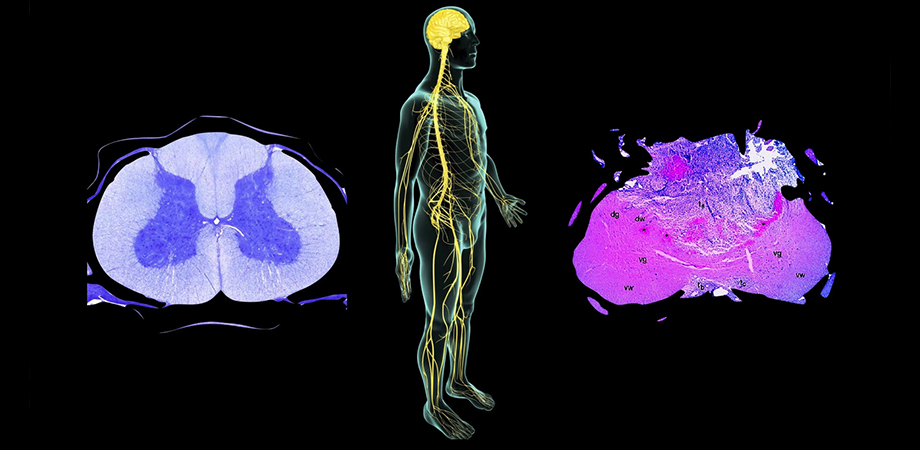

Neurointerventionalists implant the Stentrode using a catheter during a minimally invasive procedure. It goes through the jugular vein and into a large vessel near the primary motor cortex—the area of the brain that is responsible for producing movement commands. The Stentrode is the only brain-computer interface that can access the primary motor cortex with this approach, without requiring open brain surgery.

Although patients with paralysis are unable to voluntarily move their affected limbs, they still have the ability to produce brain signals in their motor cortex that can generate command functions. The Stentrode technology picks up those brain signals, then transmits them out of the brain to a small unit placed in the chest. The chest device is connected to an external receiver that converts the brain signals into commands and sends them wirelessly to a computer, allowing the patient to control it through thought. The patient can train their brain how to operate the computer and use it to communicate with family, caregivers, and friends, as well as perform other digital activities like shopping and banking.

Once the Stentrode is implanted, Dr. Putrino’s research team at the Abilities Research Center within Mount Sinai’s Department of Rehabilitation and Human Performance will work to evaluate the overall impact of this technology. They will assess the implant’s safety, and how effective it is in providing a quantifiable improvement in independence and quality of life for these patients.

The first implantation of the Stentrode technology in the United States is expected to take place within the next 12 months. Before that, researchers will perform imaging studies on healthy participants and those living with paralysis. This will help them understand what a neurotypical brain looks like from a vascular and functional perspective compared to those with paralysis. Researchers can then determine if participants with paralysis have the same capacity for supporting the brain implant in their blood vessel and producing usable brain signals as members of the general population. Having this information will allow them to create protocols for selecting patients for the study who will have good outcomes with implantation.

A recent publication in Journal of NeuroInterventional Surgery demonstrated that two Australian patients implanted with the Stentrode learned to control texting and typing through direct thought. After training on mouse-clicking, they used the system unsupervised in their homes to send text messages, shop online, and manage their finances.

“This technology can revolutionize how people with paralysis interact with the world—and the fact that it can be placed minimally invasively, without the need for open brain surgery, is simply amazing,” says Shahram Majidi, MD, Assistant Professor of Neurosurgery, Neurology, and Radiology at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and Director of Cerebrovascular Services at Mount Sinai Brooklyn, who will be implanting the devices for Mount Sinai.

Carnegie Mellon University will lead this project, and University of Pittsburgh Medical Center has been named as the other research site to study Stentrode.