Racial discrimination increases the risk for physical and mental illnesses, and Black women suffer from diseases at significantly higher rates than White women. How traumatic experiences such as discrimination increase vulnerability to illness remains the topic of intense research. Now, a new study shows that the experience of racial discrimination affects the microstructure of the brain, as well as increasing the risk for health disorders.

The study, led by Negar Fani, PhD, Emory University Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, appears in Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging.

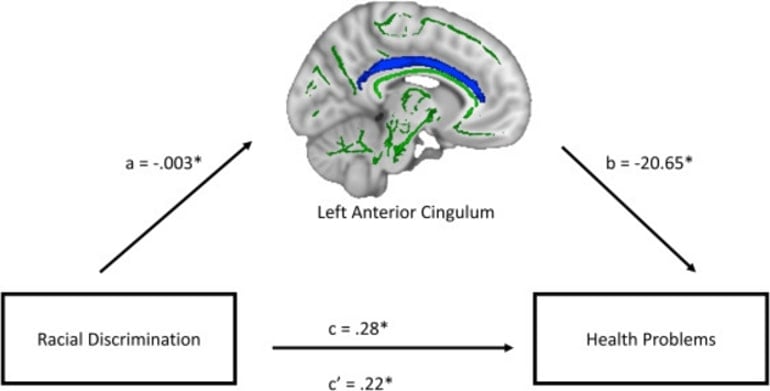

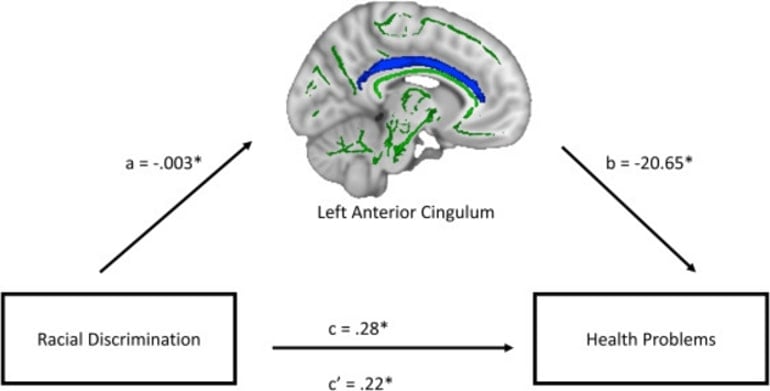

Dr. Fani said, “Here we see a pathway through which racist experiences may increase risk for health problems via effects on select stress-sensitive brain pathways. Earlier, we found that racial discrimination has a negative impact on brain white matter; now we can see that these changes may enhance risk for negative health outcomes, possibly by influencing regulatory behaviors.”

For the study, researchers recruited 79 Black women from a county hospital in Atlanta, Georgia. The women were clinically assessed for trauma and for medical disorders ranging from asthma to diabetes to chronic pain. Over half the women reported severe economic disadvantage, with a household income under $1,000 per month, for which the researchers controlled in their analysis.

The participants also underwent a brain scan using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The researchers measured the brain’s fractional anisotropy (FA), a reflection of water movement through brain white matter – specifically the long, fatty tracts that connect distant regions of the brain. Changes in FA can result from structural disruptions of white matter tracts.

Women who experienced more racial discrimination displayed lower FA in select brain tracts including the anterior cingulum bundle and the corpus callosum, which connects the two hemispheres of the brain. In addition, the structural integrity of these two specific tracts mediated the relationship between racial discrimination and medical disorders in these women.

“That points to a possible brain mechanism for adverse health outcomes,” Dr. Fani added.

Cameron Carter, MD, Editor of Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, said of the work, “These findings provide important new evidence that changes in the brain measured using MRI may occur, in association with a range of ongoing chronic health problems, in the wake of ongoing experiences of racial discrimination in African American women. Such insights may contribute to our understanding of the origins of health disparities in minoritized communities and the negative impact that racial discrimination may have on human health.”

The authors hypothesize that the burden of trauma and racial discrimination may affect brain matter integrity through the stress system. The affected tracts are involved in emotional regulation and cognitive processes, which may in turn lead to behavioral changes, such as increased consumption of drugs or foods, that increase risk for health conditions.