New insights into the opposing actions of serotonin-producing nerve fibres in mice could lead to drugs for treating addictions and major depression.

Scientists in Japan have identified a nerve pathway involved in the processing of rewarding and distressing stimuli and situations in mice.

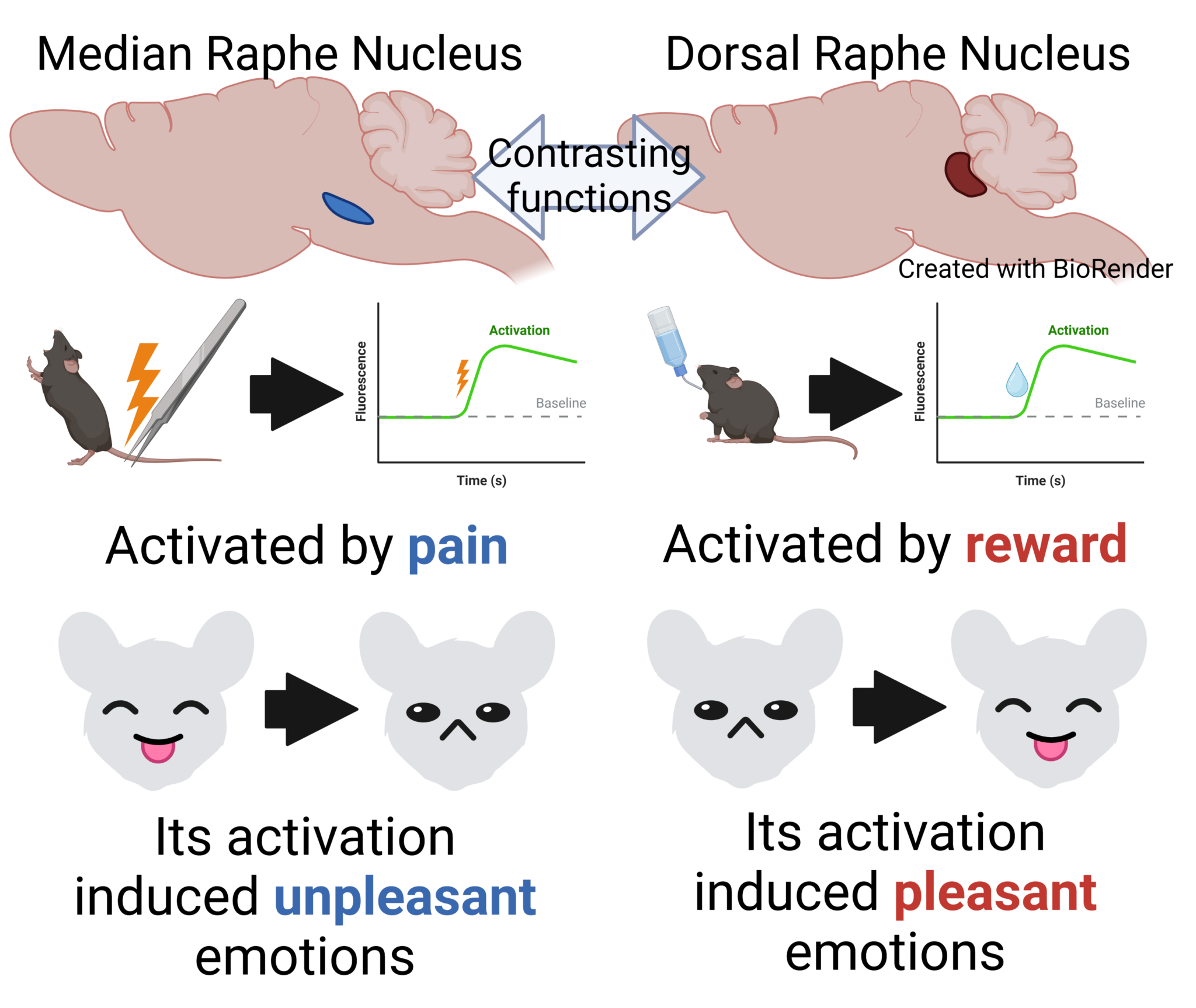

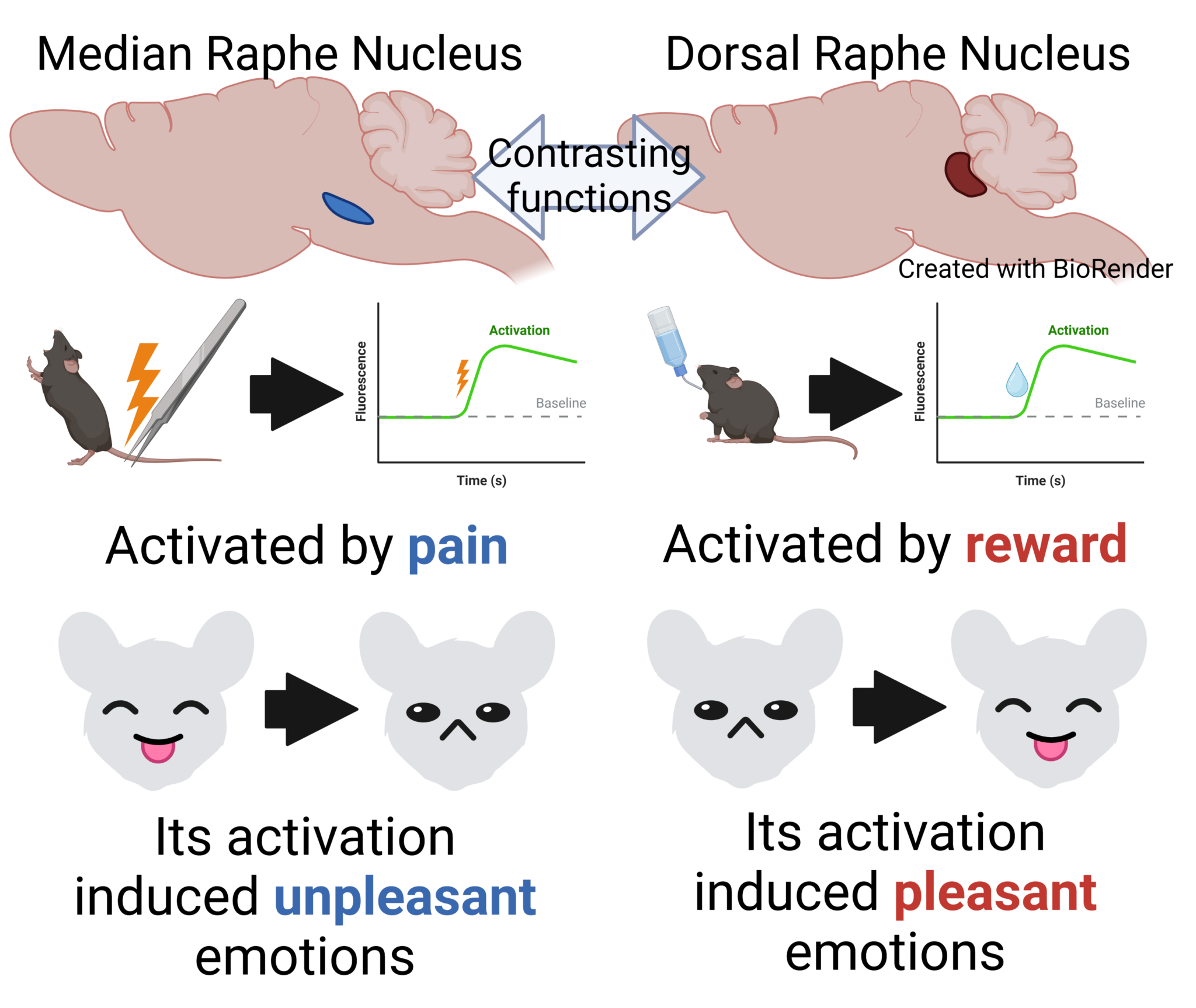

The new pathway, originating in a bundle of brain stem nerve fibres called the median raphe nucleus, acts in opposition to a previously identified reward/aversion pathway that originates in the nearby dorsal raphe nucleus. The findings, published by scientists at Hokkaido University and Kyoto University with their colleagues in the journal Nature Communications, could have implications for developing drug treatments for various mental disorders, including addictions and major depression.

Previous studies had already revealed that activating serotonin-producing nerve fibres from the dorsal raphe nucleus in the brain stem of mice leads to the pleasurable feeling associated with reward. However, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), antidepressant drugs that increase serotonin levels in the brain, fail to exert clear feelings of reward and to treat the loss of ability to feel pleasure associated with depression. This suggests that there are other serotonin-producing nerve pathways in the brain associated with the feelings of reward and aversion.

To further study the reward and aversion nerve pathways of the brain, Hokkaido University neuropharmacologist Yu Ohmura and Kyoto University pharmacologist Kazuki Nagayasu, together with colleagues at several universities in Japan, focused their attention on the median raphe nucleus. This region has not received as much research attention as its brain stem neighbour, the dorsal raphe nucleus, even though it also is a source of serotonergic nerve fibres.

The scientists conducted a wide variety of tests to measure activity of serotonin neurons in mice, in response to stimulating and inhibiting the median raphe, by using fluorescent proteins that detect entry of calcium ions, a proxy of neuronal activation in a cell-type specific manner.

They found that, for example, pinching a mouse’s tail—an unpleasant stimulus—increased calcium-dependent fluorescence in the serotonin neurons of the median raphe. Giving mice a treat such as sugar, on the other hand, reduced median raphe serotonin fluorescence. Also, directly stimulating or inhibiting the median raphe nucleus, using a genetic technique involving light, led to aversive or reward-seeking behaviours, such as avoiding or wanting to stay in a chamber—depending on the type of stimulus applied.

The team also conducted tests to discover where the switched-on serotonergic nerve fibres of the median raphe were sending signals to and found an important connection with the brain stem’s interpenduncular nucleus. They also identified serotonin receptors within this nucleus that were involved in the aversive properties associated with median raphe serotonergic activity.

Further research is needed to fully elucidate this pathway and others related to rewarding and aversive feelings and behaviours. “These new insights could lead to a better understanding of the biological basis of mental disorders where aberrant processing of rewards and aversive information occur, such as in drug addiction and major depressive disorder,” says Ohmura.