Key Findings

- Low cognitive ability, functional limitations, and poor physical health are strong predictors of dementia as many as 20 years before its onset. Lifestyle factors, such as never drinking alcohol or drinking excessively, never exercising, and low engagement in hobbies, are associated with cognitive impairment and dementia.

- Early detection of cognitive impairment helps people take mitigating actions to prepare for future loss of their financial and physical independence.

- Older adults’ take-up of cognitive testing is low, and many who do get tested exit the clinical care pathway before being diagnosed and receiving treatment. Take-up of cognitive tests would increase if tests were free and readily accessible. Treatments would be more palatable if they had fewer side effects and helped patients maintain independence longer.

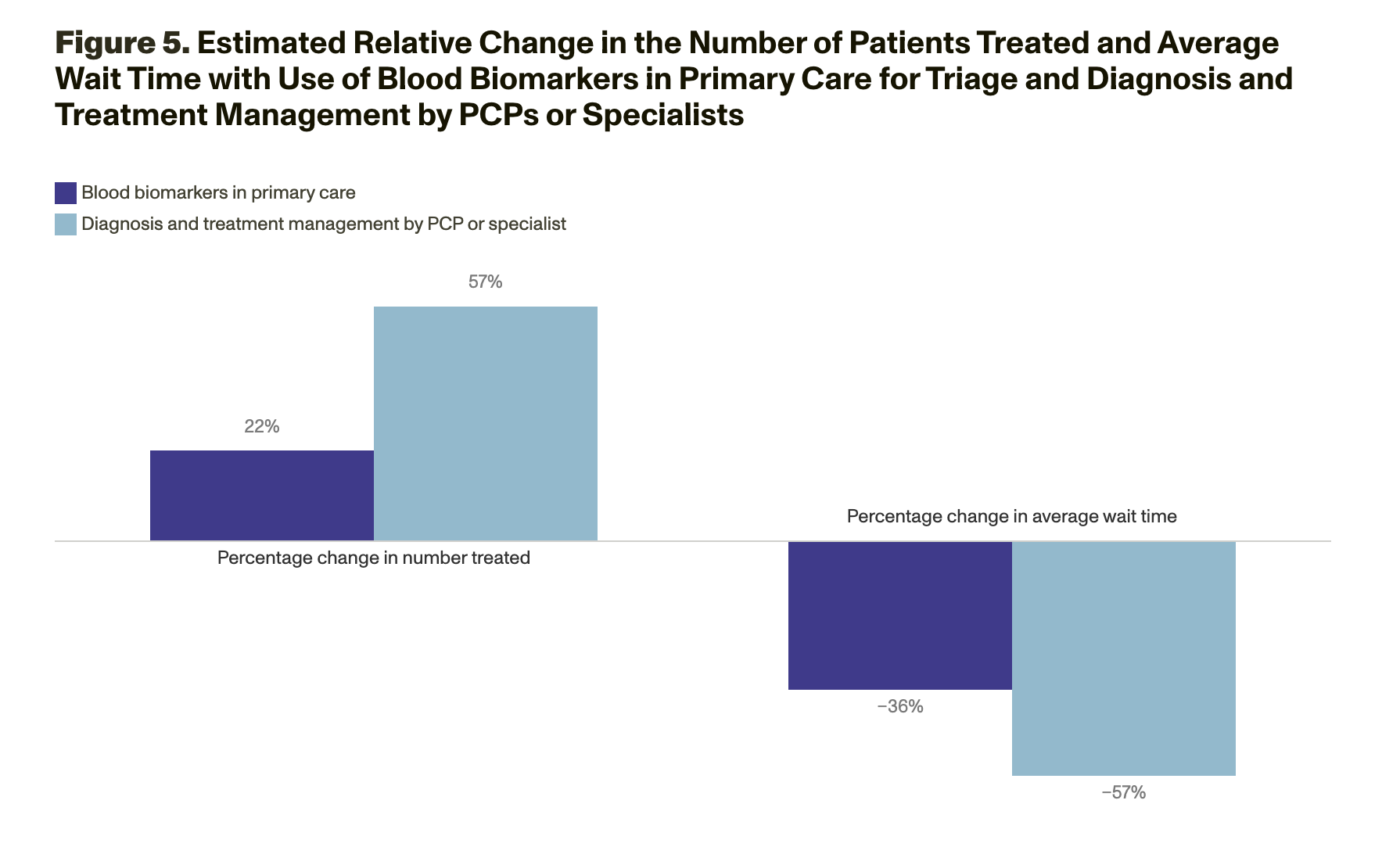

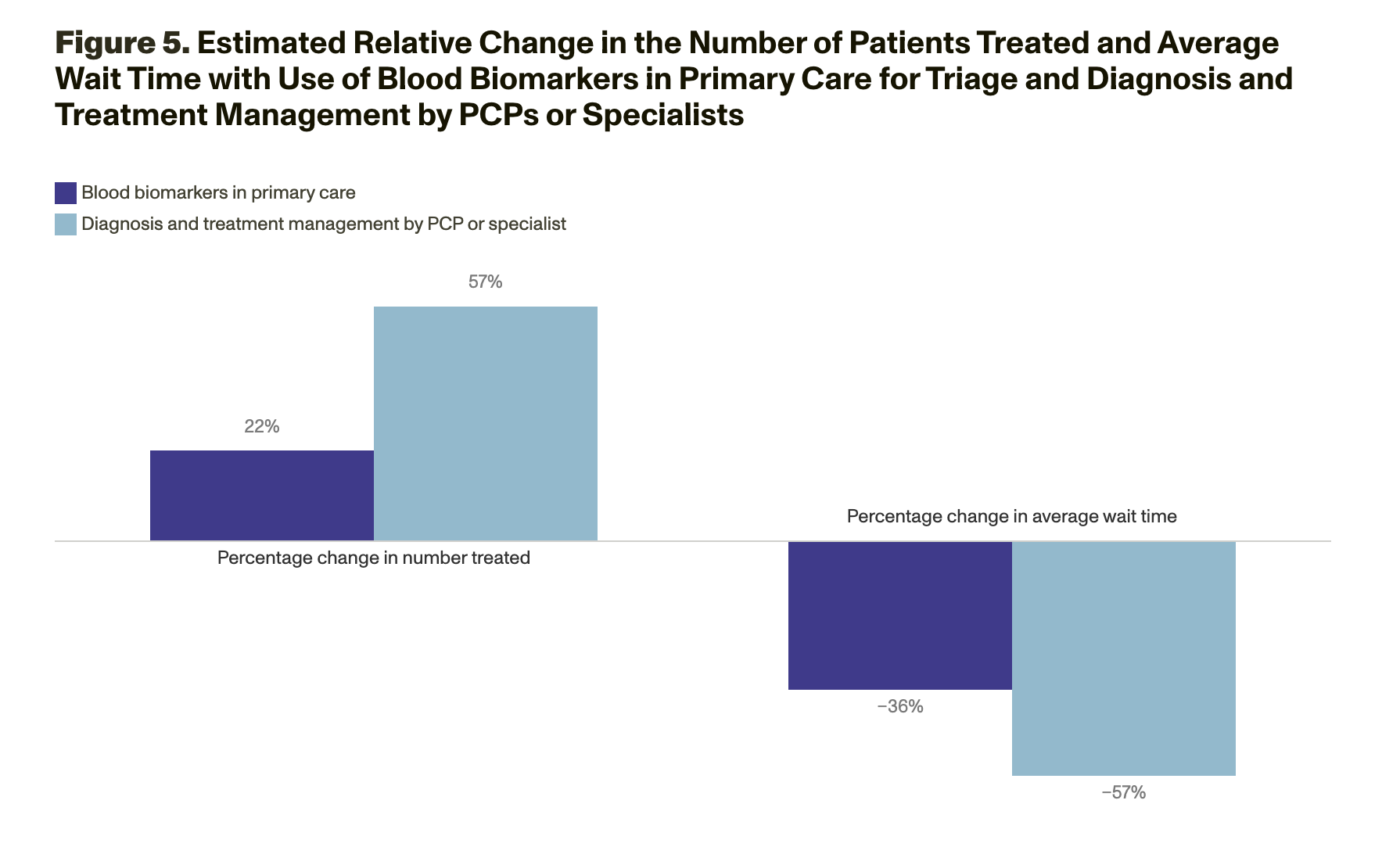

- More engagement of primary care practitioners and team-based care in the clinical care pathway and the use of new technologies, such as blood-based biomarkers, could ease health care system capacity constraints on dementia specialists and reduce wait times for patients.

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and related dementias (ADRDs) silently rob people of their memories, making it progressively more difficult for them to care for themselves and straining their caregivers. Clinical assessments of cognitive decline and ADRDs are an early step in a pathway to care that begins with detection and can include diagnosis, treatment, and social supports (Figure 1). But many people might exit the clinical care pathway before they receive care or do not enter the pathway at all. This is possibly because there is no cure, the effectiveness of existing disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) is modest, or individuals might face barriers to accessing care. Furthermore, navigating the patchwork of care and supports is difficult.

Early detection of ADRDs among the estimated 58 million U.S. citizens ages 65 and older—and among younger populations who might be affected—is critical, in part because available DMTs work only for patients who are in the early stage of disease. Early detection can also prompt patients to better prepare for cognitive decline by encouraging them to make lifestyle and financial changes. Yet cognitive testing is underused: Only about 16 percent of people ages 65 and older get a cognitive assessment during a routine visit with their primary care practitioner (PCP) (Alzheimer’s Association, 2019).

16% of people ages 65 and older get a cognitive assessment during a routine visit with their PCP.

RAND researchers conducted a series of studies to understand factors associated with brain health, take-up of cognitive testing by older adults, and continued care. The researchers used multiple approaches to identify predictors of cognitive impairment; gauge the short- and long-term benefits of early detection and advanced planning; understand patients’ demand for screening, diagnosis, and treatment; and project the capacity of the U.S. health care system to provide care to cognitively impaired individuals. This brief describes the findings of each study and the policy implications for decisionmakers to consider when trying to improve brain health and care.

Identifying Early Predictors

Assessments of cognitive impairment and early-detection tests for AD can help people understand their short-term risk for memory problems. However, if long-term risk factors were better understood, individuals in high-risk groups could prepare sooner, and health care providers and policymakers could better target resources to bolster drug development, social supports, and provider infrastructure.

RAND researchers used data from the cognition and dementia measures in the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), which has followed a nationally representative sample of about 20,000 older adults and their households in the United States since 1992, to detect whether individuals would be at elevated risk for dementia years before its onset. The researchers investigated 181 potential dementia risk factors for individuals up to 20 years in advance of diagnosis and individuals’ associated characteristics, such as demographics, socioeconomic status, labor-market measures, lifestyle behaviors, measurable health, genetics, parent health, cognitive ability, and psychosocial factors.

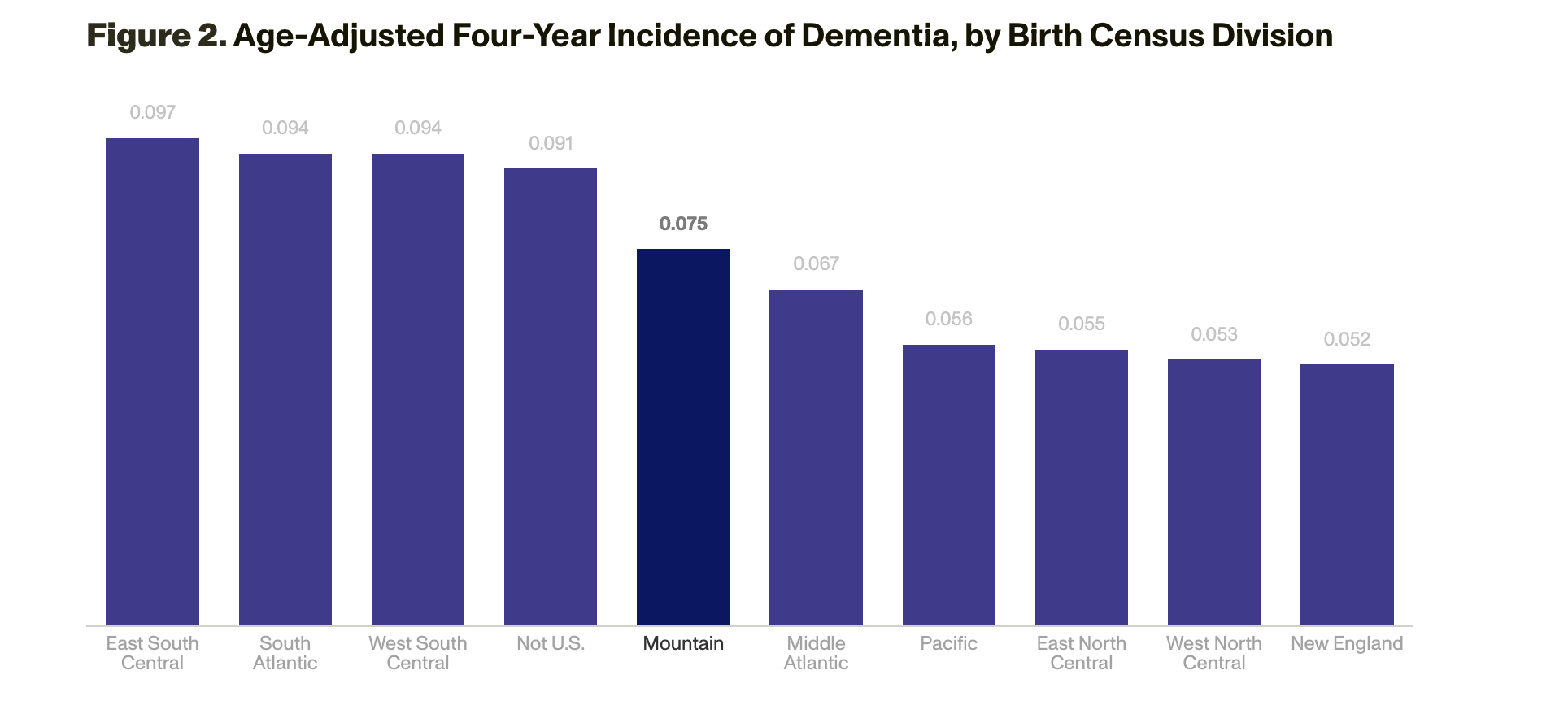

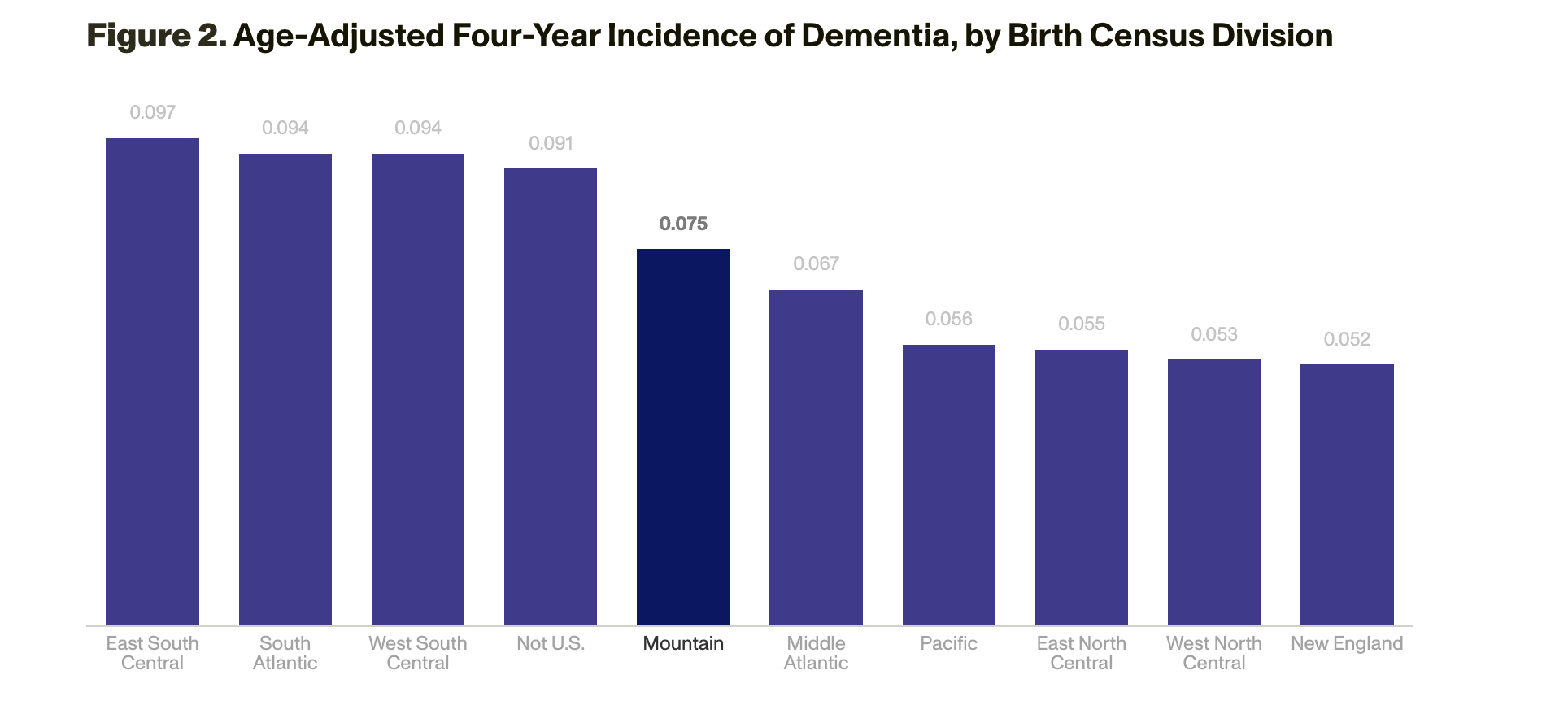

The strongest risk factors for dementia were lower baseline cognitive abilities; functional limitations, such as difficulty with bathing; and poor physical health. Lifestyle and related factors also mattered: People were more likely to develop dementia if, for example, they did not exercise, had diabetes or a high body mass index, had never worked, lacked private health insurance, never drank or excessively drank alcohol, or had few hobbies. Regional associations with risk also emerged: People born in the southeastern area of the United States had a higher risk of developing dementia than those in other areas (Figure 2). Although Black, Hispanic, and lower-income individuals had a higher risk of developing dementia, race and ethnicity were not risk factors when controlling for education and income. Parental health, family size, marital history, and other demographics were also not strong predictors of dementia.

Prior literature has established that some people perceive benefits from knowing about their cognitive health, although others would rather not know. When people are informed, they can take actions to ameliorate the consequences of ongoing and future cognitive decline. Such actions could include advanced planning of care arrangements or assistance with managing finances. However, much of the literature is based on surveys of subpopulations, such as samples from memory clinics, so these results might not be generalizable to the entire older adult population.

To better understand what actions individuals or their families take after learning of potential cognitive impairment, RAND researchers studied the relationship between individuals’ cognitive status, the mitigating actions the individuals took, and how they subsequently fared. The researchers analyzed data from the large HRS dataset and used two measures of cognitive impairment: a doctor’s diagnosis of memory-related disease and a calibrated survey-based measure of dementia status. RAND researchers related these measures to actions that individuals and their families took over time and whether these actions were associated with better health and wealth.

The survey-based measure estimated a higher rate (6.1 percent) of cognitive problems than the rate from a doctor’s diagnosis (5.5 percent), which supports the conventional wisdom that cognitive impairment is underdiagnosed. Those who received a dementia diagnosis were more likely to act: For example, approximately 25 percent of respondents who received a diagnosis indicated receiving help from their children with finances compared with only 2 percent of respondents who did not receive a diagnosis. Furthermore, even before diagnosis, people identified by the survey-based measure as having dementia were much more likely to get help with finances than others (29 percent versus 2 percent among those identified as having no dementia), which suggests that many individuals and their families might realize that they have a cognitive issue and act before a diagnosis. Individuals who received a diagnosis were more likely to establish a living will or power of attorney, reside with an adult child to receive help, move from a one-family home, and reduce financial responsibilities.

25% of respondents who received a diagnosis indicated that they received help from their children with finances.

RAND researchers investigated whether taking these actions was associated with better outcomes (in cognition, wealth, depression, life satisfaction, health, and survival) compared with not taking the actions. Individuals who have lower socioeconomic status, worse health, lower life satisfaction, and more-advanced cognitive impairment took action more frequently, but it was unclear in these data whether taking action was associated with better outcomes.

Understanding Demand for Testing, Diagnosis, and Treatment

Older adults who recognize the benefits of early testing and treatment might have concerns about cost, treatment efficacy, and other factors, which might discourage them from testing or proceeding to treatment. Few studies have estimated demand for testing and treatment and how changes in the palatability of options, such as the efficacy of DMTs, could affect demand.

Using survey responses gathered from RAND’s nationally representative American Life Panel, RAND researchers estimated the demand for cognitive tests and subsequent treatment. The research team asked respondents ages 50 to 70 about the likelihood that they would take a cognitive assessment or an early-detection test for AD, follow up with a brain specialist if recommended, and use a DMT for AD if eligible.

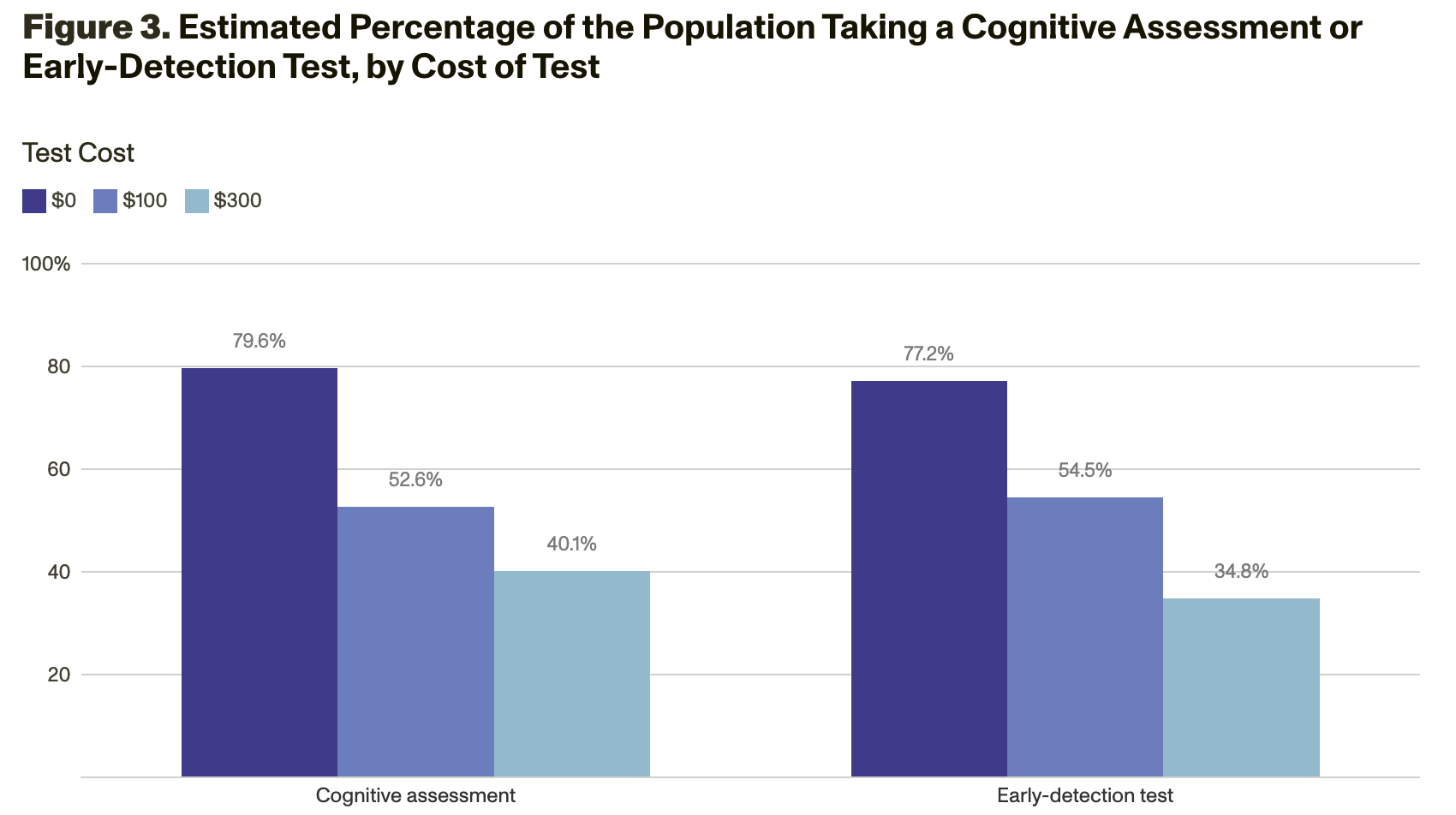

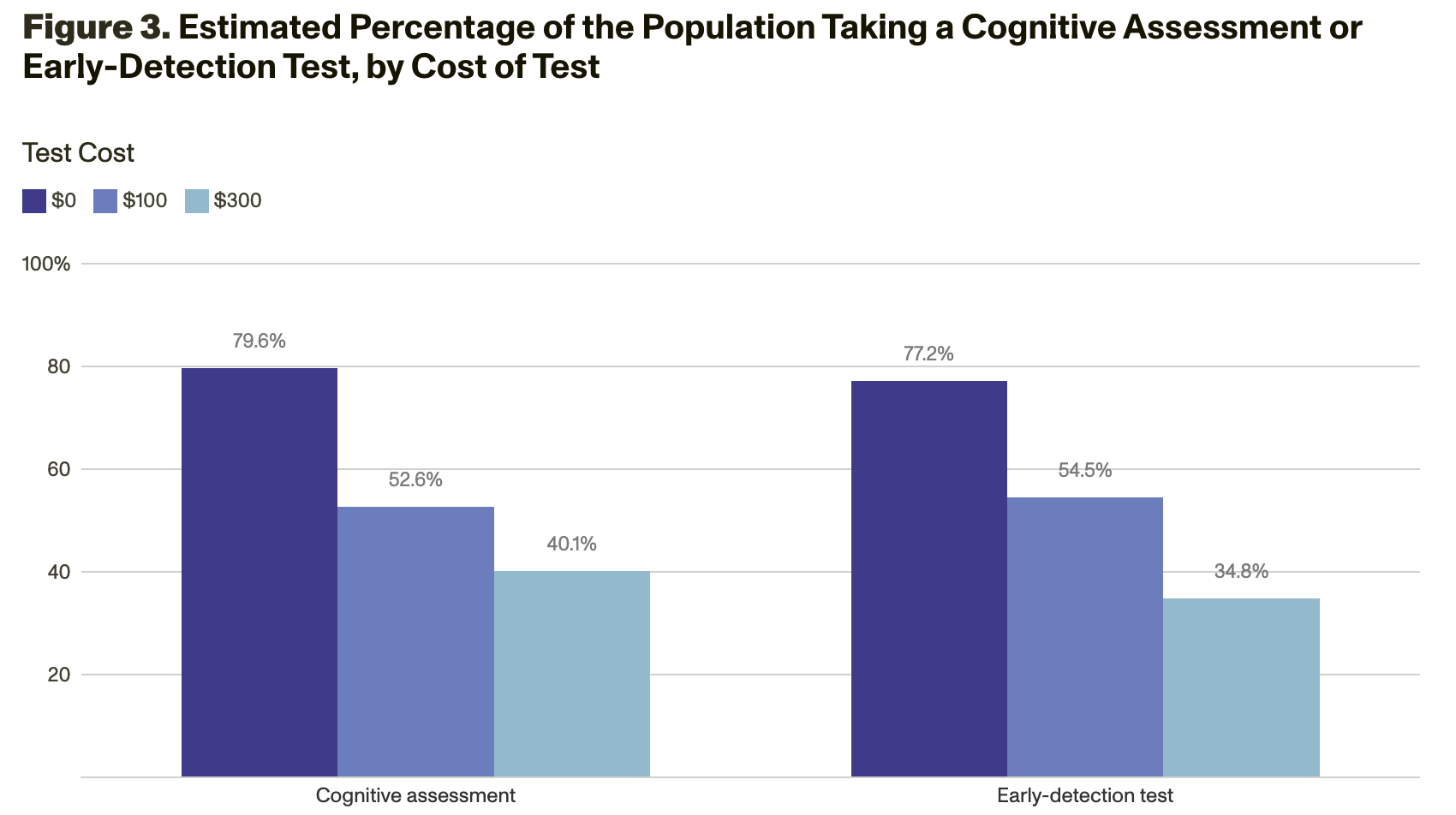

Analyses of the survey responses showed that demand for testing varies a lot by the amount of out-of-pocket costs. If testing were free, 80 percent would undergo a cognitive assessment, and 77 percent would take an early-detection test for AD. However, if testing cost $300, only 40 percent would undergo a cognitive assessment, and 35 percent would take an early-detection test for AD (Figure 3).

72% would opt to see a brain specialist… 60% would opt for a DMT if it would help them maintain independence for an additional three years… 45% would opt for a DMT if it would help only achieve six additional months of independence.

Modeling Health System Capacity

Although existing AD DMTs offer modest delays in disease progression, this class of therapies is expected to become more effective in the future. Encouraging patients to enter the clinical care pathway—and removing bottlenecks that compel them to exit prematurely—is important to ensure that patients benefit from therapeutic advances. Some barriers, such as difficulty in obtaining an appointment with a neurology or geriatric specialist, indicate that the U.S. health care system infrastructure might lack the capacity to care for all eligible patients.

To better understand where health care system bottlenecks exist, RAND researchers conducted simulation modeling to assess patients’ demand for AD DMTs and the supply of providers who perform the detection, diagnosis, and treatment management services necessary for these therapies. These models examined data on the capacity of both PCPs and specialists and incorporated county-level data to account for geographic variations in patient populations and health care system capacities because potential patients and the clinicians who can diagnose and treat them are not evenly spread throughout the United States.

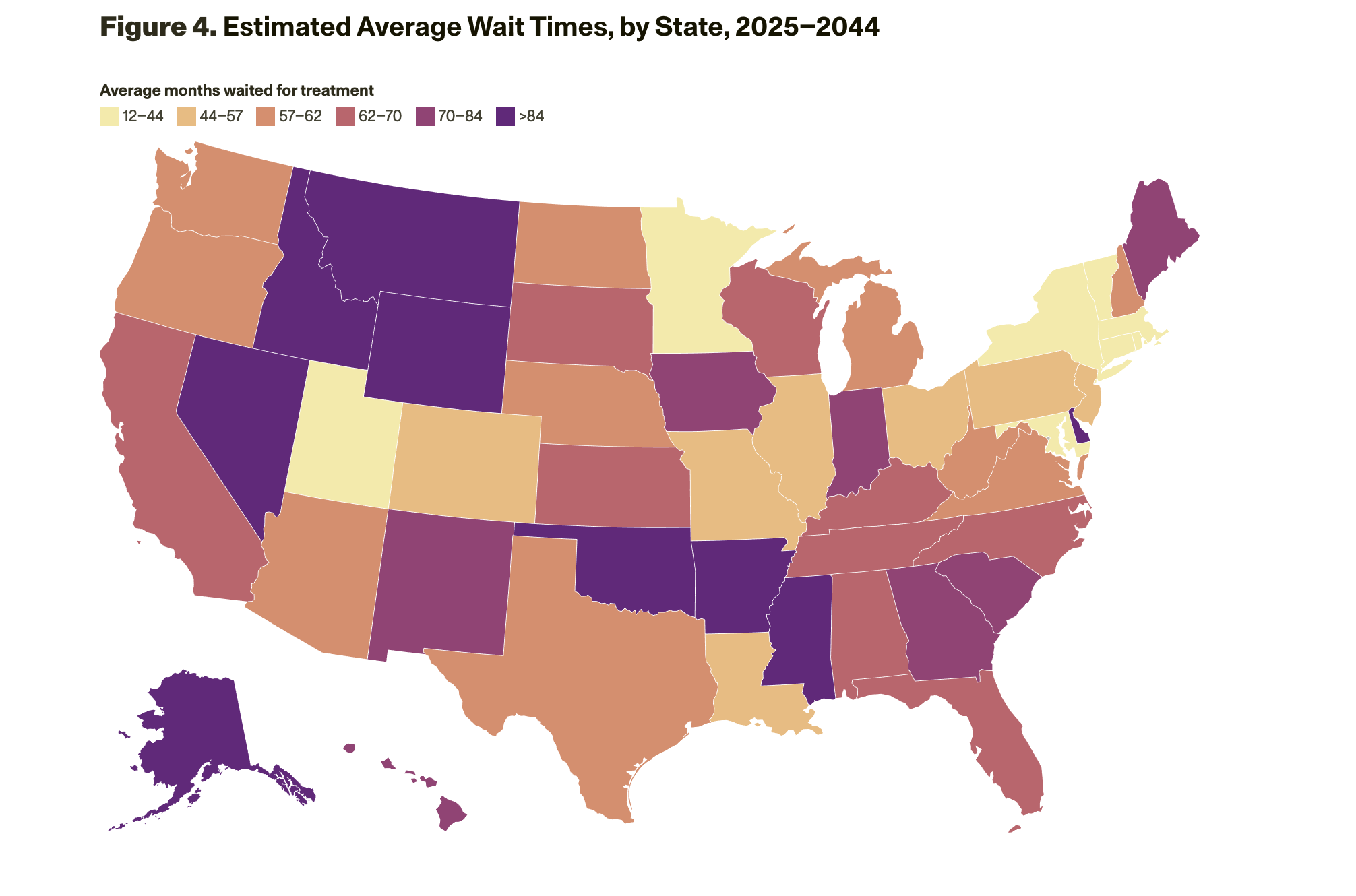

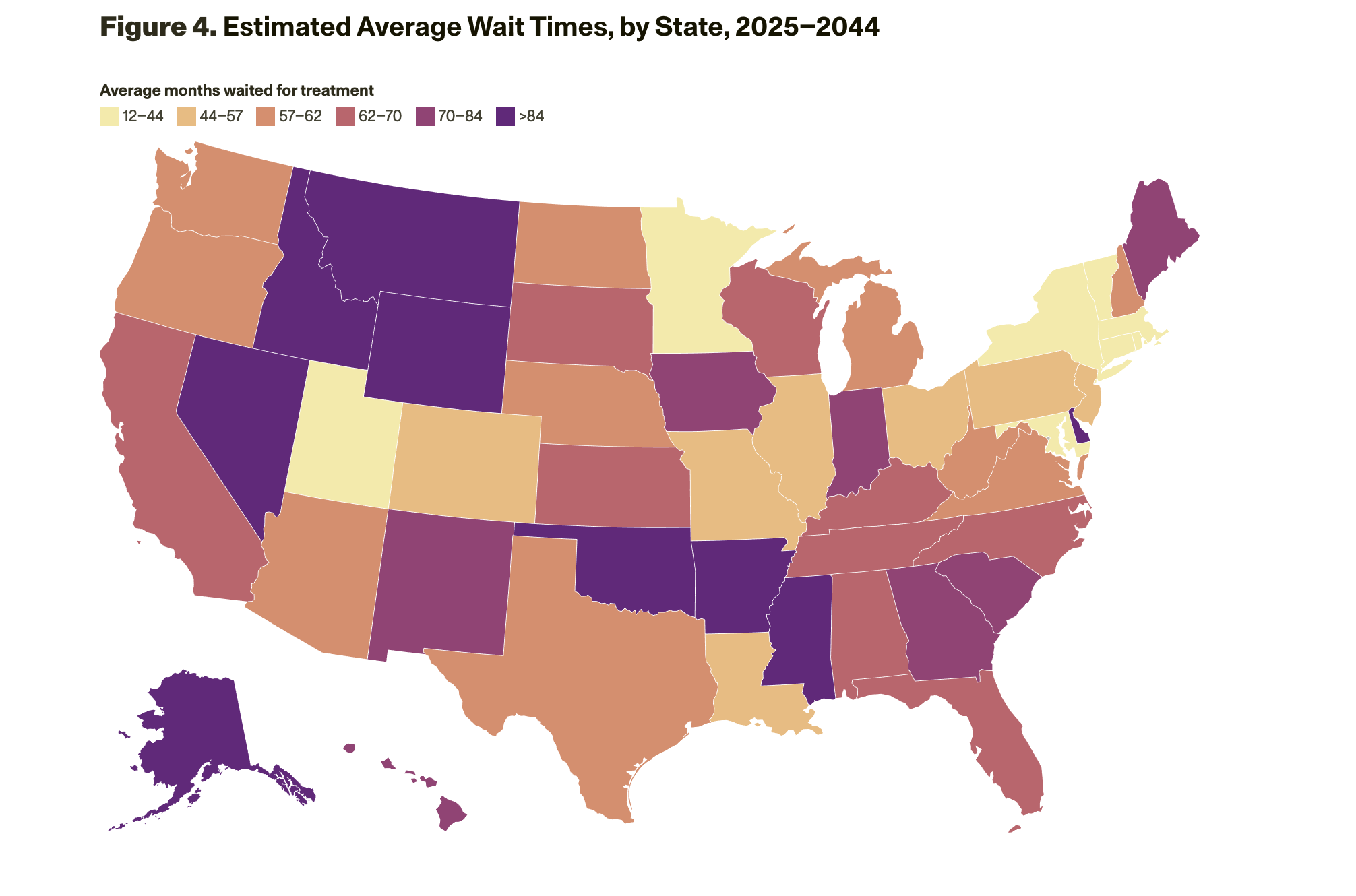

The model results suggest that without changes to capacity, millions of patients would be likely to experience long wait times (of about 18 months on average initially and up to 55 months, on average, as prevalent cases are seen) to see a dementia specialist (neurologist, geriatrician, and geriatric psychiatrist), during which their cognitive function would decline. Wait times for patients living in rural areas would be about three times longer than for those living in urban areas. The states that have the longest wait times are Alaska, Arkansas, Idaho, Mississippi, Montana, Nevada, Oklahoma, and Wyoming (Figure 4).

Policy Implications

The findings of all four studies have wide-ranging implications for policies that encourage more-proactive care for brain health so that patients enter the clinical care pathway and remain in care as needed. Decisionmakers across many sectors—health and community services providers; health care system leaders; insurers; federal, state, and local government policymakers; and drug manufacturers—should consider the following inter-related issues to best support ADRD patients, their families, and their caregivers:

Prevention. Policies and public health activities that promote brain health—such as exercise, healthy eating, and participation in hobbies or activities that involve incorporation of new information—could help reduce the risk of cognitive decline at a population level.

Education and communications. Improved communications with older adults about the risk of cognitive decline, mitigation strategies, and the benefits of cognitive assessments and early detection could help lower barriers to entering and navigating the care pathway. Training in how to communicate effectively about ADRDs and the importance of doing so could be especially helpful for health care and social support providers who interact with at-risk patients.

Early detection. Cognitive assessments and validated blood-based biomarkers (when available) could be integrated into primary care clinical workflows (such as annual visits), and payment policies could help promote these assessments and tests through adequate pro- vider payment and low patient cost sharing.

Diagnosis. Using team-based, collaborative care models could reduce bottlenecks to care, and telehealth options could also help address geographic limitations of provider availability.

Treatment. Patient demand for DMTs could shift if there were fewer side effects and if the therapies significantly increased patients’ years of independence.

Download Research, Published courtesy of RAND.