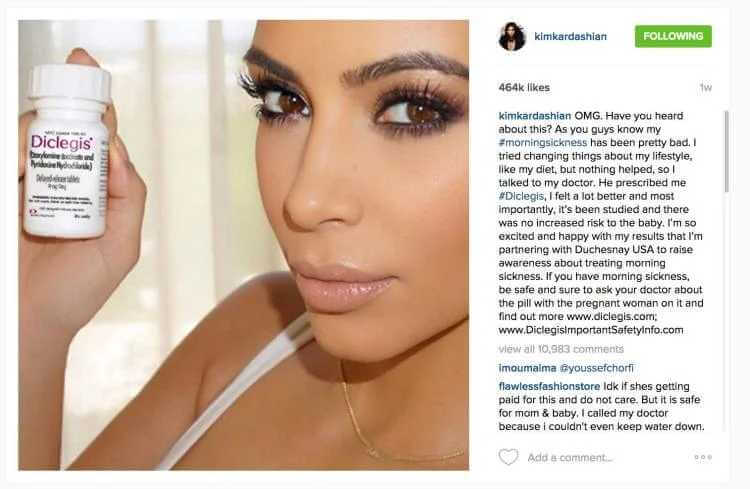

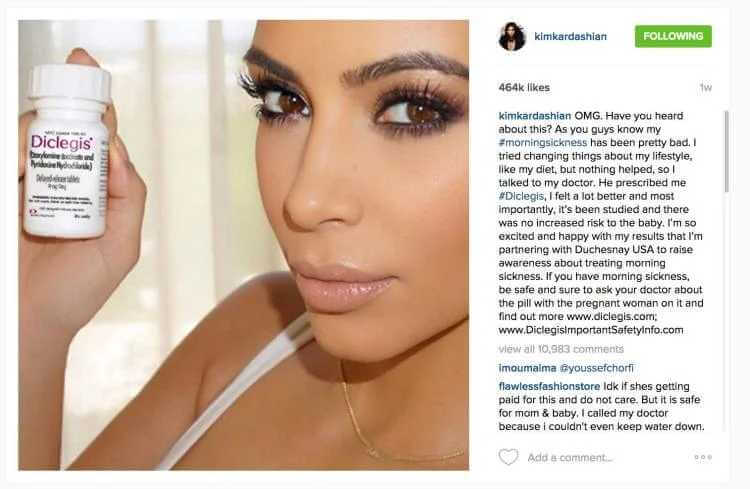

“OMG. Have you guys heard about this?”

So began a 2015 post by then-pregnant celebrity influencer Kim Kardashian, singing the praises of a “#morningsickness” drug called Diclegis to her tens of millions of followers on Instagram.

“It’s been studied and there’s no increased risk to the baby,” she wrote, alongside a smiling selfie of her holding the pill bottle. “I’m so excited and happy with the results.”

The Food and Drug Administration swiftly flagged the post for omitting risks, required Kardashian to remove the post and dinged the drug maker with a warning letter.

But seven years later, so-called patient influencers are alive and well, with pharmaceutical companies increasingly partnering with real-life patients who share their personal stories and advocate for brands online.

This trend intrigues and concerns Erin Willis, an associate professor of Advertising, Public Relations and Media Design at CU Boulder. In a new paper, published in the Journal of Medical Internet Research, she calls on the academic community to take a closer look.

“This is a growing phenomenon, but there is virtually no research on it and very little regulation,” said Willis, who is interviewing dozens of patient influencers for a new study. “Is it going to help patients be better informed? Or is it going to get patients to ask their doctors for drugs they don’t really need? We just don’t know, because no one has studied it.”

New twist on ‘direct to consumer’ marketing

In one of the first academic papers to date to explore the phenomenon, Willis and co-author Marjorie Delbaere, a professor of marketing at the University of Saskatchewan, framed patient influencers as “the next frontier in direct-to-consumer (DTC) pharmaceutical marketing.”

The controversial form of marketing, legal only in the United States and New Zealand, enables drug companies to target consumers directly, rather than through physicians. Since the first DTC ad ran in the 1980s, the ads have exploded, leading patients to ask their doctors about drugs they see on TV or in print. As Willis notes, about 44% who ask their doctor about a drug, get it.

Today, with trust in pharmaceutical companies, doctors and traditional media all declining, drug makers are now turning to patients themselves as messengers, with companies like WEGO health connecting patient influencers to healthcare companies for paid partnerships.

Having learned from the Kardashian incident, many ad agencies now avoid celebrity influencers altogether and instead engage “micro-influencers” like individual patients who share their personal stories and endorsements in condition-specific support groups (diabetes, heart disease, etc.) or those with a niche social media following.

“It’s a lot like what we used to see with doctors and pharmaceutical companies,” said Willis. “Only now it is patients using social media to advocate for disease awareness, and in some cases—pharmaceutical medications.”

A blurring of the lines between ad and opinion

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) now requires that patient influencers disclose whether they are being paid (influencers use #ad or #sponcon to alert followers). And the FDA has published rules about what can and cannot be said on social posts. But such rules are open to interpretation and hard to enforce, said Willis.

The authors also have concerns that “a blurring of the lines” between ad and opinion could potentially deceive patients.

“When you see an ad and you recognize it as such, you are aware of the intent and you process it differently,” said Delbaere.

As with any social media influencer, a patient influencer might omit crucial information, such as the availability of a cheaper generic option, or unintentionally disseminate misinformation due to lack of scientific expertise. But when health conditions or drugs are the subject of the posts, the stakes can be higher than with something like shoes or make-up, said Willis.

Upsides for patients and advertisers

All that said, she also sees many upsides to the patient influencer revolution. Patients often know more than their doctors about what it’s like to experience a health condition, and sharing that expertise can potentially help other patients discover treatments they’re unaware of.

And unlike other forms of DTC advertising, social media is interactive.

“If an influencer recommends a drug, there is an entire community of voices that get to weigh in on it and support it or share their negative experiences,” said Willis.

Thus far in her interviews of patient influencers, Willis said she has found that only a small number are paid to post (some get free trips to conferences or are paid to sit on advisory boards). Some aren’t paid at all.

“They all say they are really doing this so that other patients have information and can have a better life,” said Willis. “That is their No. 1 motivation and I think that’s awesome.”

She said she hopes that her work, funded in part by the Arthur W. Page Center for Integrity in Public Communication, and the new research agenda she has launched, will lead to a set of best practices for both patient influencers and the companies they work with.

“There is both value and risk in this growing trend and, like anything, it has the potential to become dangerous if we’re not careful,” Willis said.