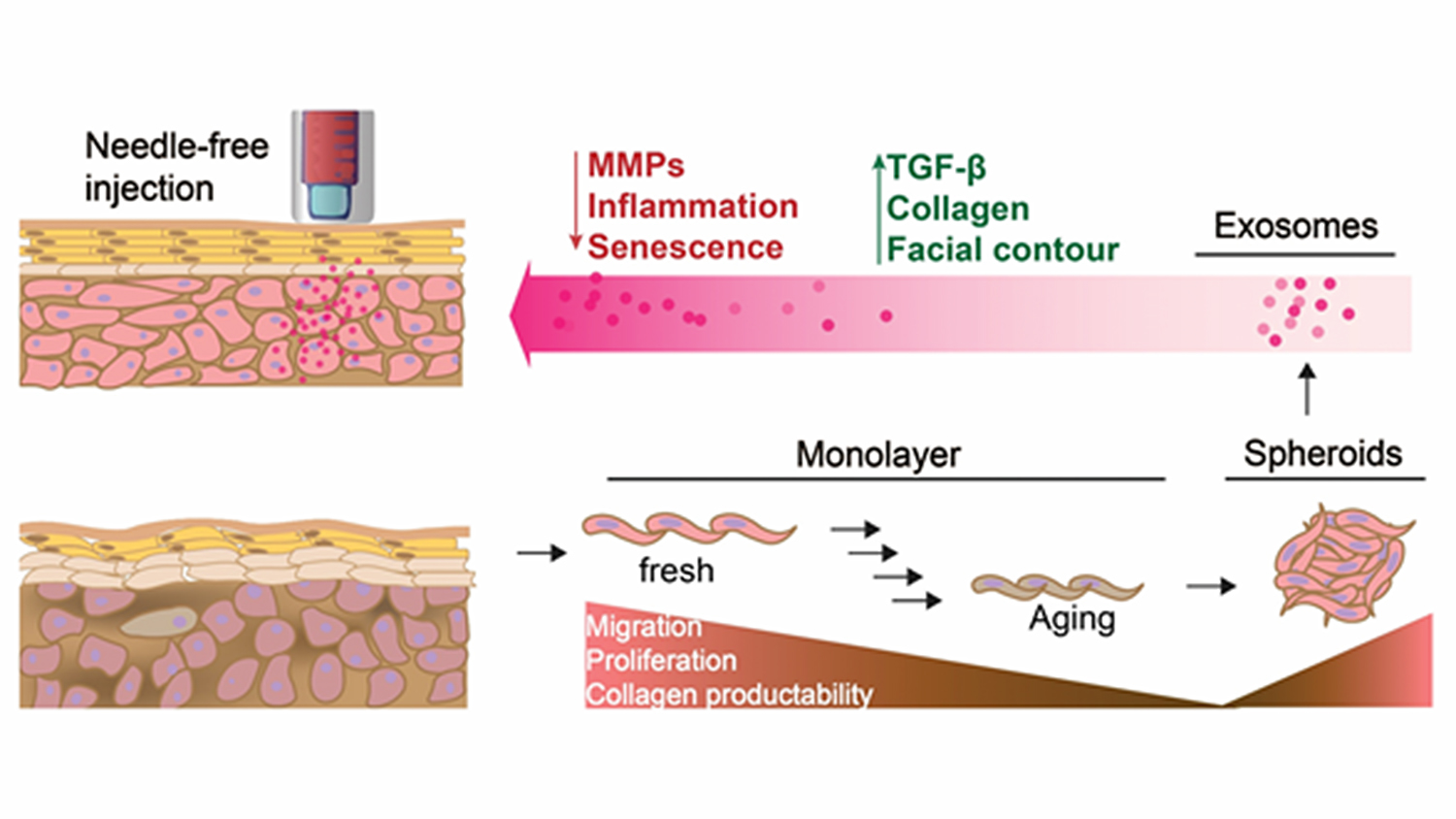

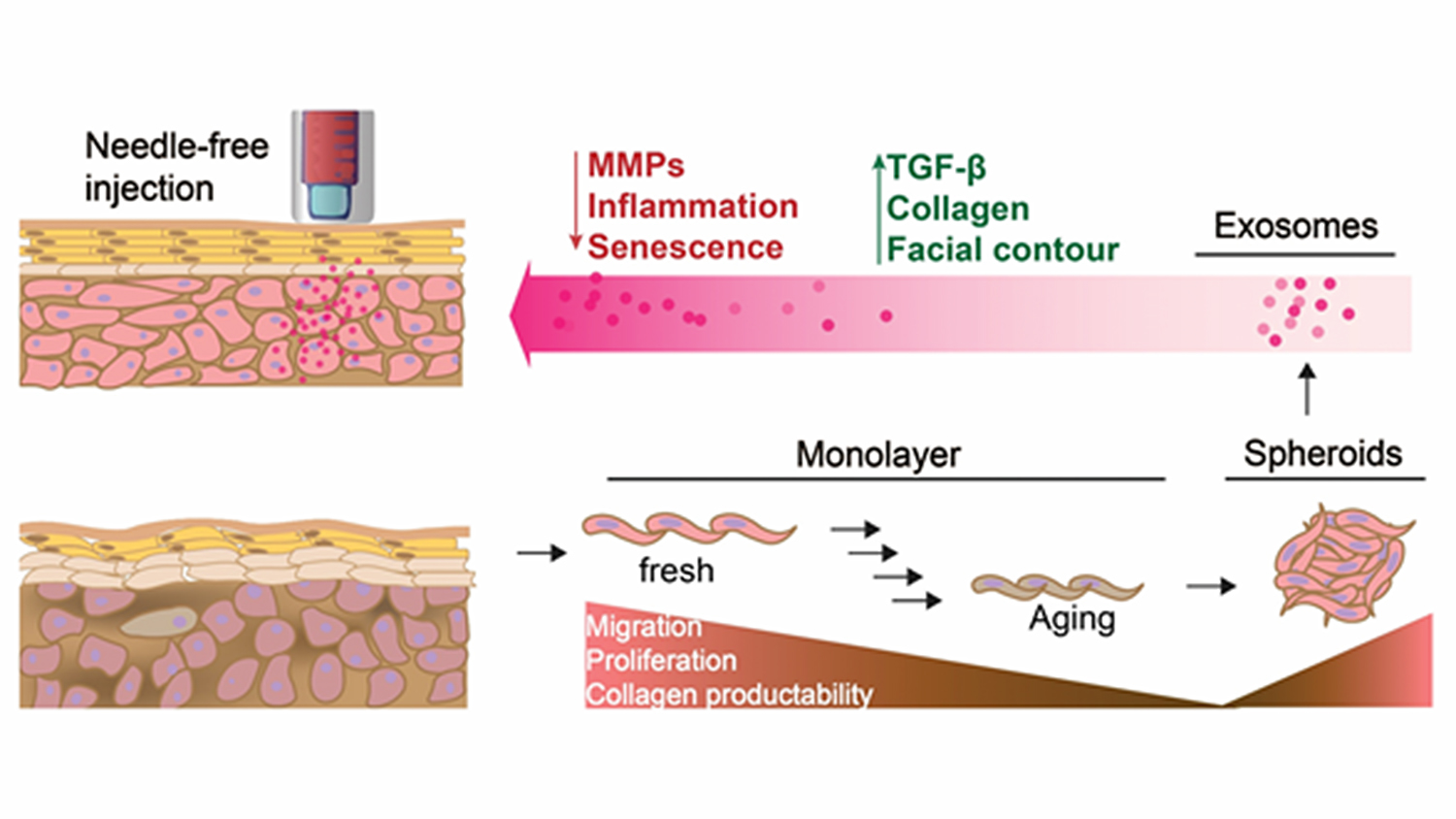

In the future, you could be your very own fountain of youth – or at least your own skin repair reservoir. In a proof-of-concept study, researchers from North Carolina State University have shown that exosomes harvested from human skin cells are more effective at repairing sun-damaged skin cells in mice than popular retinol or stem cell-based treatments currently in use. Additionally, the nanometer-sized exosomes can be delivered to the target cells via needle-free injections.

Exosomes are tiny sacs (30 – 150 nanometers across) that are excreted and taken up by cells. They can transfer DNA, RNA or proteins from cell to cell, affecting the function of the recipient cell. In the regenerative medicine field, exosomes are being tested as carriers of stem cell-based treatments for diseases ranging from heart disease to respiratory disorders.

“Think of an exosome as an envelope with instructions inside – like one cell mailing a letter to another cell and telling it what to do,” says Ke Cheng, professor of molecular biomedical sciences at NC State, professor in the NC State/UNC-Chapel Hill Joint Department of Biomedical Engineering and corresponding author of a paper describing the work. “In this case, the envelope contains microRNA, non-coding RNA that instructs the recipient cell to produce more collagen.”

To test whether exosomes could be effective for skin repair, Cheng and his team first grew and harvested exosomes from skin cells. They used commercially available human dermal fibroblast cells, expanding them in a suspension culture that allowed the cells to adhere to one another, forming spheroids. The spheroids then excreted exosomes into the media.

“These 3D structures generate more procollagen – more potent exosomes – than you get with 2D cell expansion,” says Cheng.

In a photoaged, nude mouse model, Cheng tested the 3D spheroid-grown exosomes against three other treatments: retinoid cream; 2D-grown exosomes; and bone marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) exosomes, a popular stem cell-based anti-aging treatment currently in use. The team compared improvements in skin thickness and collagen production after treatment. They found that skin thickness in 3D exosome treated mice was 20% better than in the untreated and 5% better than in the MSC-treated mouse. Additionally, they found 30% more collagen production in skin treated with the 3D exosomes than in the MSC treated skin, which was the second most effective treatment.

“I think this study shows the potential for 3D exosomes to be used in anti-aging skin treatments,” says Cheng. “There are two major benefits to exosome treatments over conventional treatments: one, you can use donor skin cells from anyone to grow and harvest these exosomes – they aren’t cells, so you don’t run the risk of rejection. And two, the treatment can be administered without needles – exosomes are small enough to be able to penetrate the skin via pressure, or jet injection methods.

“Our hope is that eventually people may be able to ‘bank’ skin samples and come back to them, or use donor exosome treatments that they can administer themselves. We believe that this work is an important step toward potentiating future human clinical trials in the prevention and treatment of cutaneous aging.”