The use of opioids to soothe the pain of a pulled tooth could be drastically reduced or eliminated altogether from dentistry, say University of Michigan researchers.

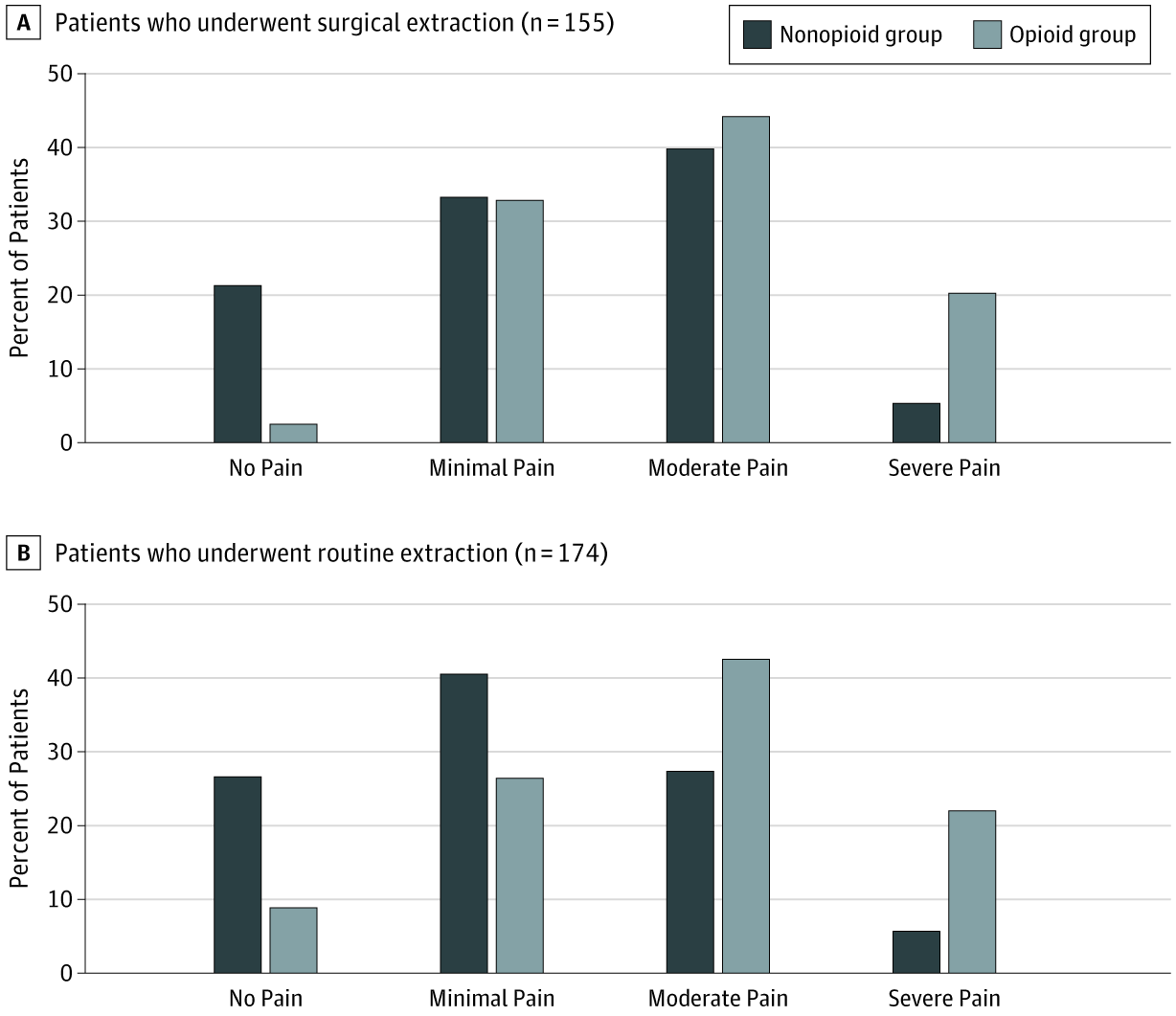

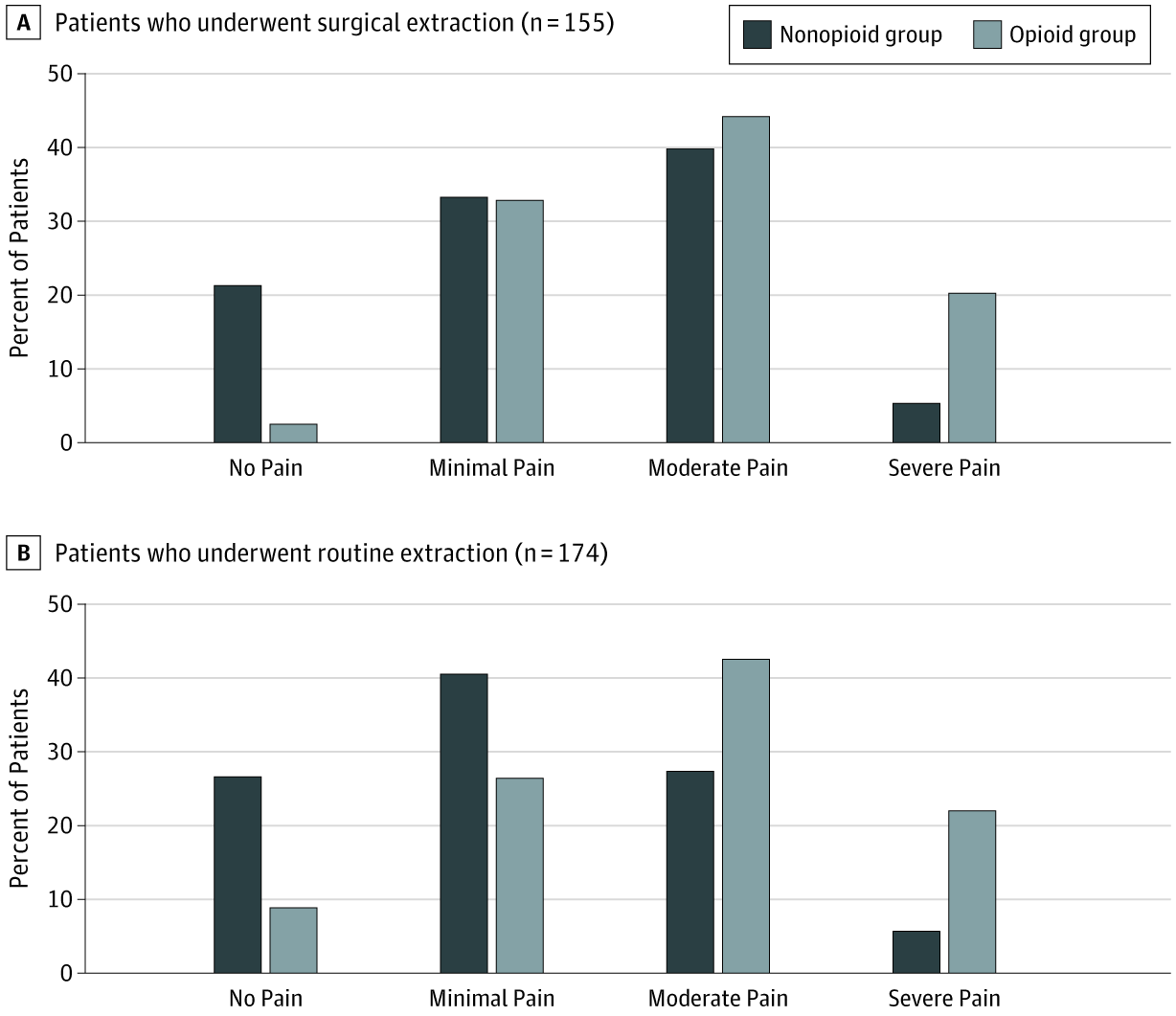

More than 325 dental patients who had teeth pulled were asked to rate their pain and satisfaction within six months of extraction. Roughly half of the study’s patients who had surgical extraction and 39% who had routine extraction were prescribed opioids.

The U-M researchers compared the pain and satisfaction of those who used opioids to those who didn’t.

“I feel like the most important finding is that patient satisfaction with pain management was no different between the opioid group and non-opioid group, and it didn’t make a difference whether it was surgical or routine extraction,” said study co-author Romesh Nalliah, clinical professor and associate dean for patient services at the U-M School of Dentistry.

Surprisingly, patients in the opioid group actually reported worse pain than the non-opioid group for both types of extractions, Nalliah said.

The researchers also found that roughly half of the opioids prescribed remained unused in both surgical and nonsurgical extractions. This could put patients or their loved ones at risk of future misuse of opioids if leftover pills are not disposed of properly.

The findings appear in JAMA Network Open.

“The real-world data from this study reinforces the previously published randomized-controlled trials showing opioids are no better than acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for pain after dental extraction,” said study co-author Chad Brummett, director of the Division of Pain Research and of Clinical Research in the Department of Anesthesiology at Michigan Medicine, U-M’s academic medical center.

Brummett co-directs the Michigan Opioid Prescribing Engagement Network, or Michigan OPEN, which has developed, tested and shared guidelines for the use of opioids in patients with acute pain from surgery and medical procedures.

“These data support the Michigan OPEN prescribing recommendations calling for no opioids for the majority of patients after dental extractions, including wisdom teeth extraction,” he said.

The results have big implications for both patients and dentists, and suggest prescribing practices need an overhaul, Brummett and Nalliah said.

The American Dental Association suggests limiting opioid prescribing to seven days’ supply, but Nalliah believes that’s too high.

“I think we can almost eliminate opioid prescribing from dental practice. Of course, there are going to be some exceptions, like patients who can’t tolerate nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories,” he said. “I would estimate we can reduce opioid prescribing to about 10% of what we currently prescribe as a profession.”

For dentists, many of whom are sole proprietors, this new information means they needn’t worry so much about unhappy patients changing practices if they aren’t prescribed strong opioids. Alternatives such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or acetaminophen appear to control pain better, and patient satisfaction remains high.

Nalliah gives two possible reasons for this. First, dentists may have prescribed opioids in only the toughest cases, which would have resulted in more pain regardless.

“Or alternatively, and this is the reason I tend to accept, is that our study concurs with previous studies that suggest opioids are not the most effective analgesic for acute dental pain,” Nalliah said.

“Dentists are torn between wanting to satisfy patients and grow business and limiting their opioid prescribing in light of the current crisis. I think it’s an extremely liberating finding for dentists who can worry more about the most effective pain relief rather than overprescribing for opioids.”

Dentists account for about 6% to 6.5% of U.S. opioid prescriptions–a relatively small amount. But the study notes that dentists are among the most common prescribers for minors, and for many patients, dental opioid prescriptions are their first exposure.