For more than two decades since 2001, the suicide rate has been rising in the general U.S. population, especially among veterans. This Veterans’ Issues in Focus essay is an update of our 2021 publication on this topic, and we present updated data on the magnitude of the problem, identify noteworthy issues and trends, highlight notable advances since 2021, and identify gaps that deserve increased attention from both researchers and policymakers. Federal, state, and local governments have prioritized preventing veteran suicide, and many nonprofit and private organizations are also lending their expertise. This essay is written with these audiences in mind.

Magnitude of the Problem

In 2022 (the most recent year for which data are available), 6,407 veterans and 41,484 nonveteran adults died by suicide. Because there are many more nonveterans in the U.S. population, the rate of suicide among veterans was 34.7 per 100,000, compared with 17.1 per 100,000 for nonveterans (Office of Suicide Prevention, 2024b).

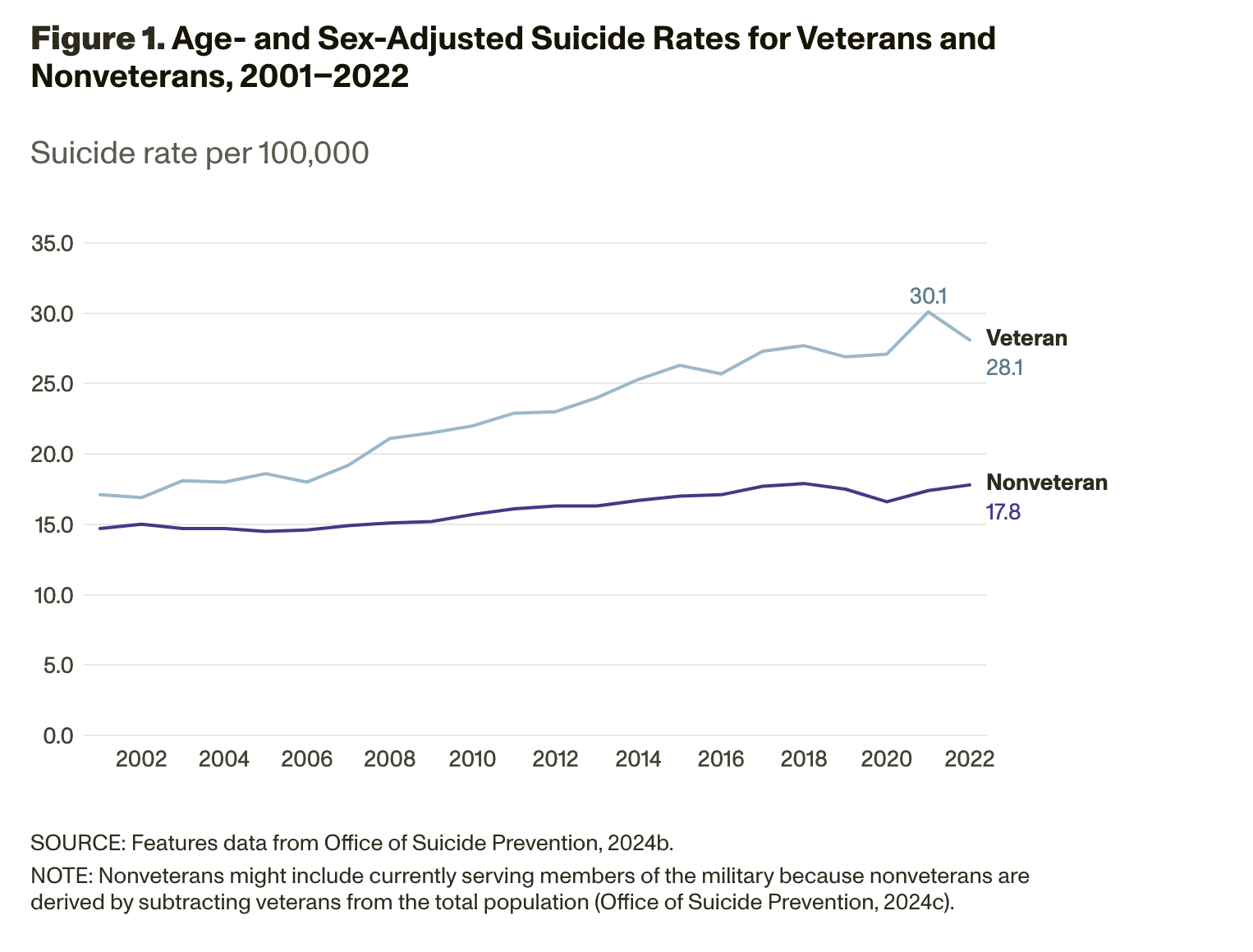

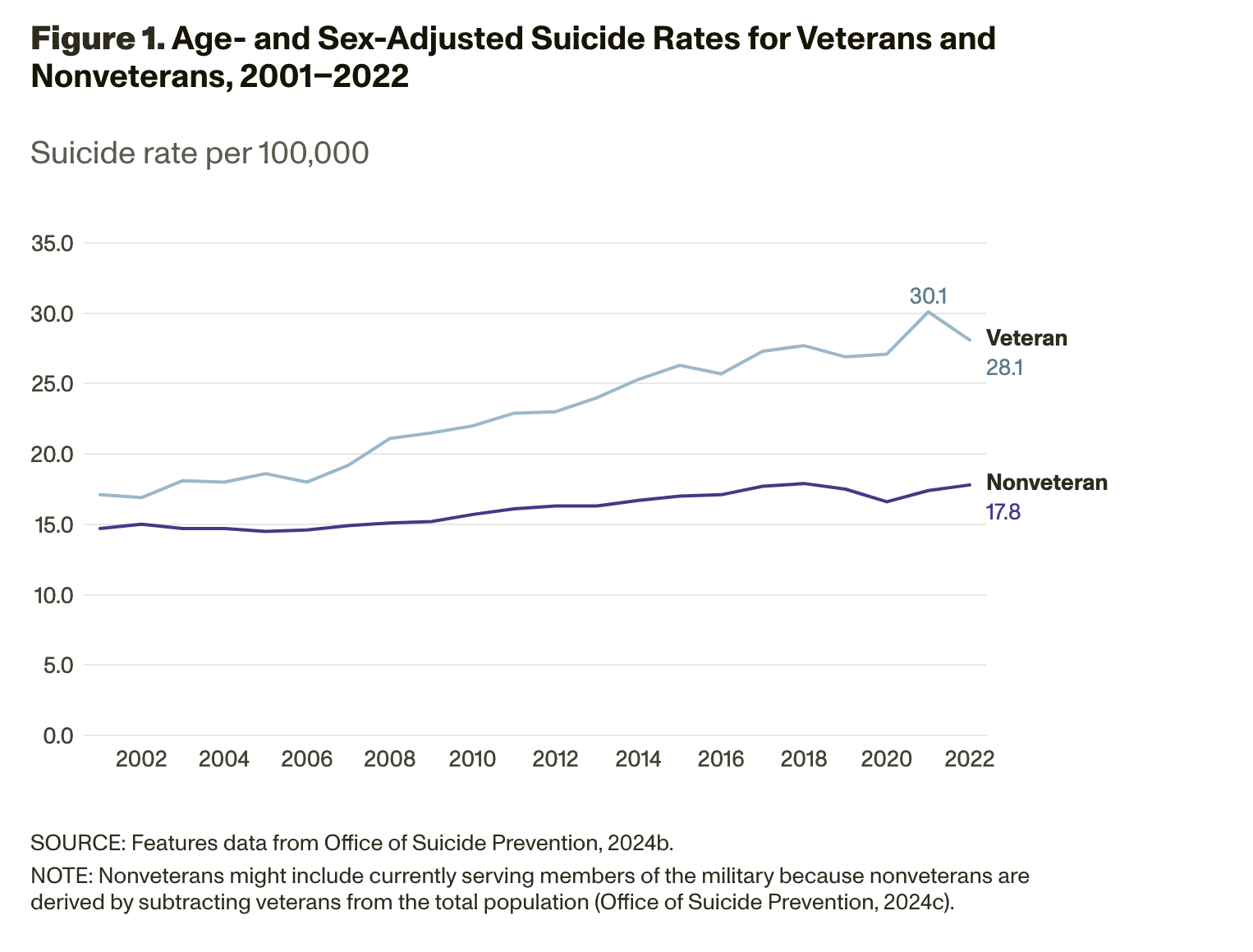

Each year, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Office of Suicide Prevention releases critical statistics on veteran suicides in its National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report. To examine trends over time, VA presents the veteran and nonveteran suicide rates adjusted to account for population differences between nonveterans and veterans, the latter of whom are younger and more are male. VA does this comparison by making both groups resemble the distribution of the U.S. adult population in 2000. Figure 1 shows age- and sex-adjusted suicide rates for veterans and nonveterans from 2001 to 2022. Since 2005, the suicide rate has risen faster for veterans than it has for nonveteran adults, although the veteran suicide rate decreased slightly between 2021 and 2022 (Office of Suicide Prevention, 2024b).

Here, we revisit the pressing issues that we identified in 2021 (when the most recent data available were from 2018), relying on data from 2022 (the most recent available data).

Suicide rates remain highest among veterans ages 18–34, although most veterans who die by suicide are age 55 or older.

In 2022, the suicide rate among 18–34-year-olds remained the highest among all age groups, at 47.6 per 100,000, equating to 849 deaths. Veterans age 55 or older make up nearly two-thirds of all U.S. veterans. In 2022, veterans age 55 or older accounted for 60 percent of all veteran suicides; there were 3,860 deaths in this group, corresponding to a rate of 32.2 per 100,000 (Office of Suicide Prevention, 2024b).

Suicide rates are still elevated among men and women veterans relative to their civilian counterparts.

In 2022, the suicide rate for male veterans was 44 percent higher than for nonveteran men (the age-adjusted rates were 42.7 versus 29.6 per 100,000), while the suicide rate for female veterans was 92 percent higher than for of nonveteran women (the age-adjusted rates were 14.2 versus 7.4 per 100,000). In total, 271 female veterans and 6,136 male veterans died by suicide that year (Office of Suicide Prevention, 2024b).

Firearms continue to be the leading method for veterans who died by suicide.

In 2022, 74 percent of veteran suicides involved firearms. Since 2001, the veteran firearm suicide rate has increased by 65 percent, relative to a 40-percent decrease in suffocation suicides and a 7.5-percent decrease in poisoning suicides (Office of Suicide Prevention, 2024b). In 2022, 45.4 percent of female veteran suicides involved firearms, relative to 34.5 percent of nonveteran women suicides, equating to a firearm suicide rate among female veterans that is 144.4 percent higher than nonveteran women. Among men, firearms accounted for 74.8 percent of veteran suicides relative to 57.4 percent of nonveteran suicides, a 69.6-percent difference (Office of Suicide Prevention, 2024b).

Veterans who received mental health diagnoses had significantly elevated suicide risk.

Among the veterans who died by suicide in 2022, 40 percent had received care from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) in the year of their death or the prior year. Among these veteran patients, the suicide rate for those who were diagnosed with a mental health disorder or substance use disorder was 56.4 per 100,000, which was nearly twice the rate of those without such diagnoses (29.6 per 100,000). Among the 1,548 veterans who died by suicide with these diagnoses, 64 percent were diagnosed with depression (65.1 per 100,000), 43 percent had an anxiety disorder (60.3 per 100,000), 40 percent had posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (51.3 per 100,000), and 32 percent had alcohol use disorder (92.1 per 100,000), making these the most common diagnoses. However, the highest suicide rates — reflecting the greatest risk — were associated with veterans who had a sedative use disorder (e.g., benzodiazepines, barbiturates) (236.7 per 100,000, accounting for 2 percent of suicides among veterans with mental health or substance use disorders) or psychoses (207.1 per 100,000, accounting for 6 percent of suicides among veterans with mental health or substance use disorders) (Office of Suicide Prevention, 2024b).

Veterans at Elevated Risk of Suicide

In this 2025 update, we highlight new information on subpopulations of veterans at increased risk of suicide who might warrant tailored suicide prevention services. These align with groups that VA‘s Office of Suicide Prevention has also identified as subpopulations of focus (Office of Suicide Prevention, 2024a).

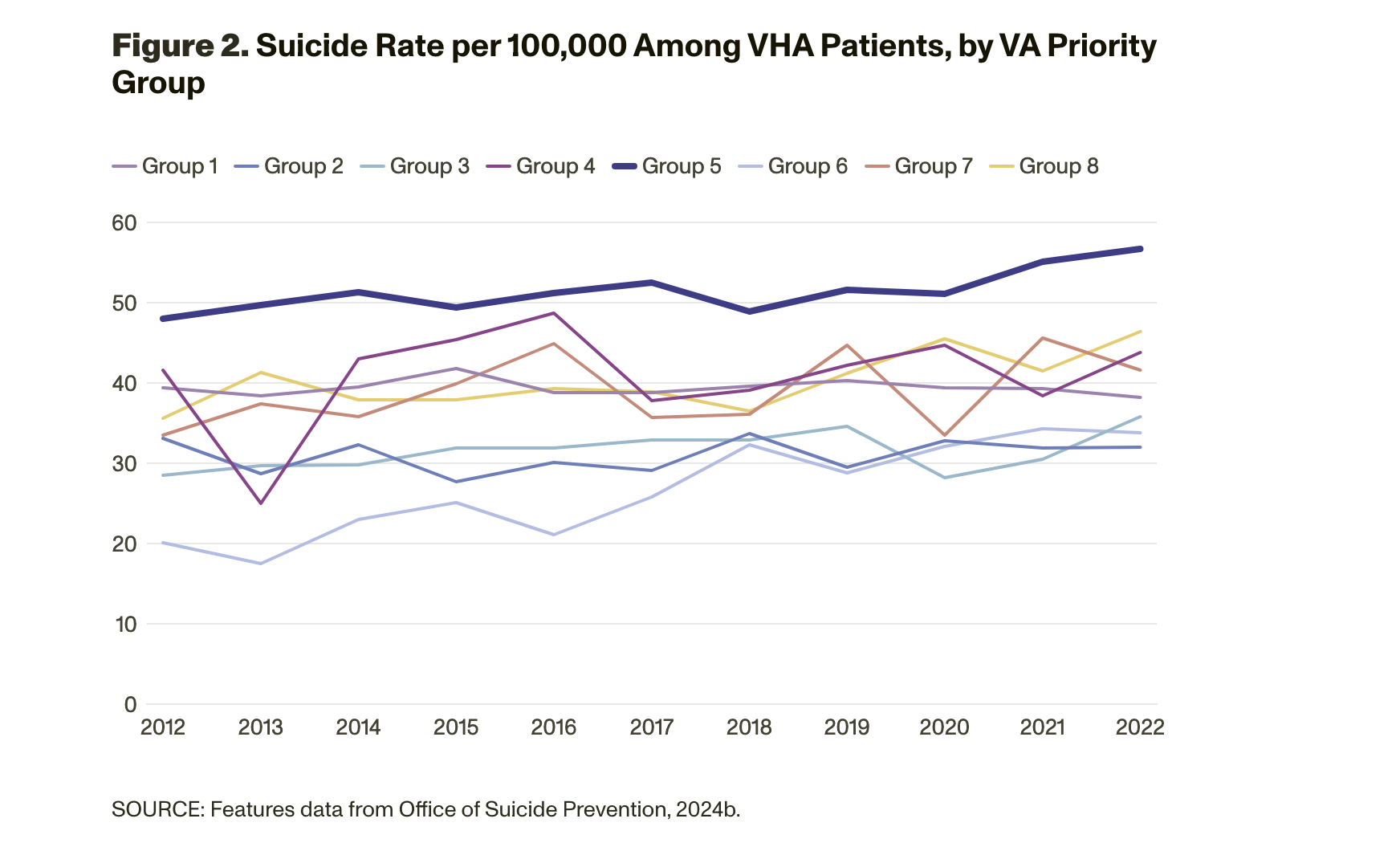

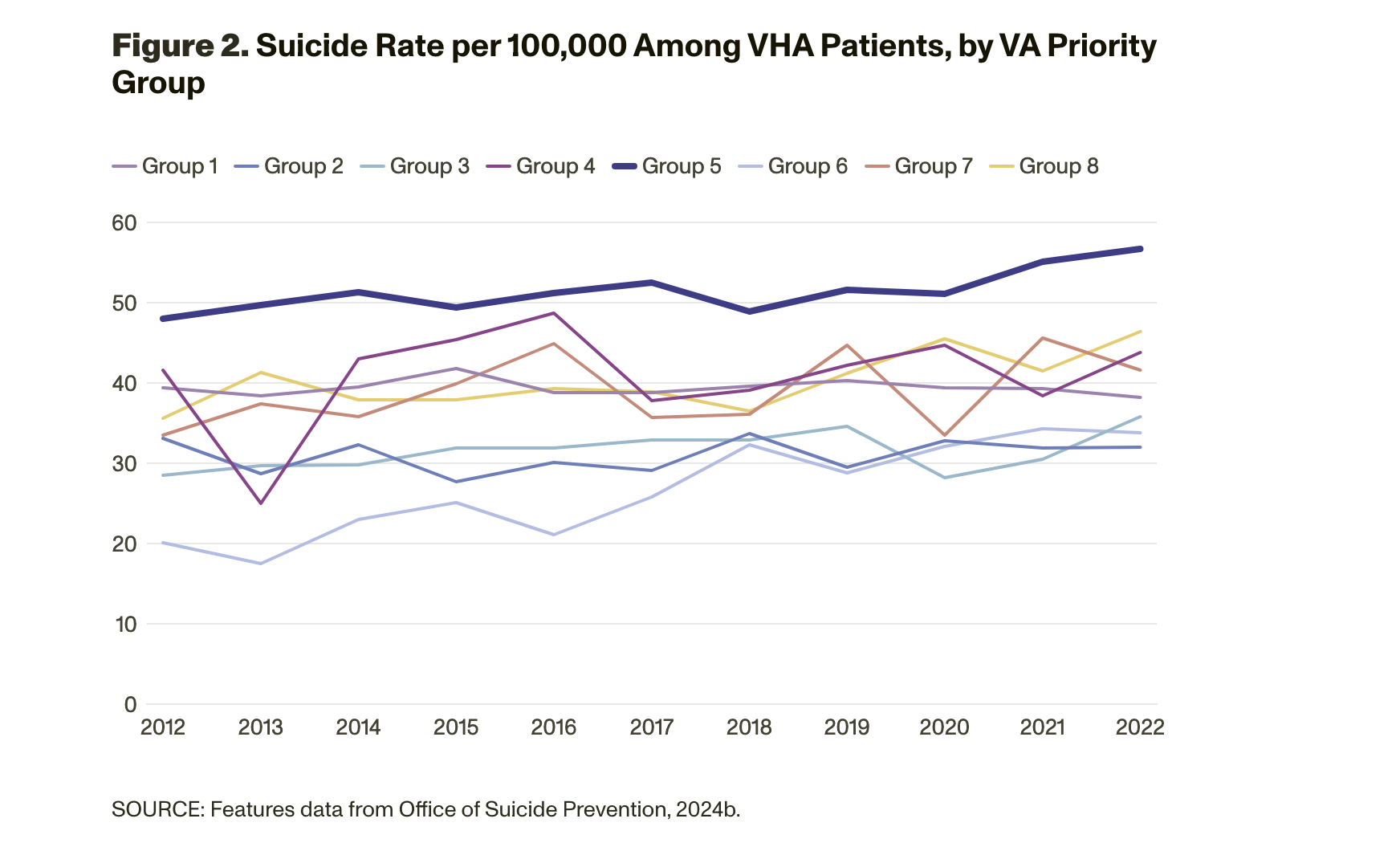

Among veterans receiving VHA care, those who had limited economic resources consistently had elevated suicide rates.

VA assigns a priority group to veterans who access VHA care (numbered 1 through 8) according to various factors, including service history, disability rating, income, and eligibility for other programs. The second largest group is Priority Group 5, which includes veterans eligible for care because of low income rather than a service-connected disability; in 2024, this group accounted for 759,704 VHA patients (VA, 2024a). From 2012 to 2022, veterans in Priority Group 5 consistently had the highest suicide rate, which is presented in Figure 2 (descriptions of other priority group criteria are available at Office of Suicide Prevention, 2024b).

Veterans who have documented past military sexual traumas (MSTs) are at a higher risk of suicide (Kimerling et al., 2016). VA conducts universal MST screening for all VHA patients; in 2022, the suicide rate among those who screened positive for MST was 25.0 per 100,000, compared with 14.3 per 100,000 for those who screened negative. Among male veterans who screened positive for MST, the suicide rate was 75.5 per 100,000; for female veterans who screened positive, the suicide rate was approximately 25.0 per 100,000 (Office of Suicide Prevention, 2024b).

Veterans who recently separated from the military have elevated suicide rates.

The risk of suicide is higher after leaving the military than during military service (Reger et al., 2015), and the risk steadily increases during the first year following separation (Ravindran et al., 2020). Certain groups of veterans, particularly younger veterans and those who had two or fewer years of military service, might be more vulnerable to suicide risk after separation (Ravindran et al., 2020). In 2021, the suicide rate for veterans in the 12 months following military separation was 46.2 per 100,000, compared with the overall rate of 34.7 per 100,000 (Office of Suicide Prevention, 2024b).

VHA patients who received community care (versus care delivered directly by VHA) had elevated suicide rates.

Veterans enrolled in VHA are increasingly eligible for care funded by VA but delivered in the community, largely because of the 2014 Veterans Choice Act and the 2018 MISSION Act (Rasmussen and Farmer, 2023). In 2022, the suicide rate among VHA patients using only community care or a combination of community and direct VHA care was 50.9 per 100,000. The rate was lower for those using only direct VHA care, at between 30 and 40 per 100,000 (data are presented in the source document in a figure without more-precise estimates). These differences could be attributed to the varying characteristics of veterans who choose community care. For instance, 20 percent of veterans who exclusively used community care are in Priority Group 5, compared with 14 percent of those using direct VHA care and 16 percent of those receiving both community and direct care (Office of Suicide Prevention 2024a; Office of Suicide Prevention, 2024b).

Veterans who had other than honorable discharges had elevated suicide rates.

Veterans who had other than honorable (OTH) discharges face a significantly higher risk of suicide, and suicide rates among this group are twice as high (45.84 per 100,000 person-years) as those of veterans with honorable discharges (22.41 per 100,000 person-years) (Reger et al., 2015). Although OTH discharges are typically given for a “significant departure from the conduct expected of enlisted Service members” (U.S. Department of Defense, 2024, p. 35), certain groups, including those who have traumatic brain injuries, PTSD, or substance use disorders, are disproportionately affected (Highfill-McRoy et al., 2010; U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2017). OTH discharges can affect veterans’ eligibility for VA health care, medical services, and other benefits (Clague et al., 2024), although policy changes have expanded access to some mental and behavioral health services, including emergency suicide care, for veterans with OTH discharges (VA, 2019).

Notable Advances in Efforts to Prevent Veteran Suicide

The rate of veteran suicide reflects thousands of lives lost each year, and such premature deaths continue to warrant attention from VA, other federal agencies, state and local governments, and organizations that serve veterans. There have been some notable advances in research and practice that might help reduce suicide among veterans.

VA‘s universal suicide screening program identifies veterans at risk of suicide and engages them in mental health care.

Since 2018, VHA has screened for suicide risk among veterans receiving primary care, care in the emergency department, and specialty mental health care through VHA using a protocol called VA Suicide Risk Identification Strategy (Risk ID). In 2020, VA expanded this program and required all veterans receiving care at VHA be screened for suicide annually (Newell et al., 2021). Researchers at VA have rigorously evaluated Risk ID. The screening did not overwhelm the system from 2018 to 2019, because less than 5 percent of patients screened positive for suicide risk. Those who screen positive for suicide risk are provided a more comprehensive assessment of risk, and those who received this more comprehensive assessment had a higher probability of accessing and engaging in mental health care, especially those who were not currently engaged in the mental health care system (Bahraini et al., 2020).

However, some providers have expressed concern about the time requirements to administer the second-stage screen (Dobscha et al., 2023). Research has identified potential ways to shorten the second-stage screening to focus on the factors that are most predictive of future suicide attempts, such as suicide ideation, firearm availability, direct suicide preparations, reckless behaviors, and history of psychiatric hospitalization (Saulnier, 2025).

VA‘s REACH VET program identifies and provides care to high-risk veterans.

Created in 2017, VA‘s Recovery Engagement and Coordination for Health – Veterans Enhanced Treatment (REACH VET) tool uses data from VHA electronic health records and predictive algorithms to assess suicide risk. Patients who have a risk score at the top 0.01 percent of the stratum — a population that has a suicide rate 39-times higher than the general veteran patient population — are contacted by the VHA provider who most closely worked with them to collaborate on reducing their risk (Matarazzo et al., 2022). There is some evidence that the algorithmic approach might be well received by some high-risk veterans (i.e., very few report privacy concerns or increased feelings of hopelessness when presented with vignettes describing REACH VET; see Reger et al., 2021), and an outcome evaluation at one VA medical center found that, within six months, most of the veterans identified by the program received some form of intervention afterward, including outpatient mental health treatment, psychiatric hospitalization, or safety planning — and none died by suicide (du Pont, 2022). However, the program was not necessarily well received by all clinicians (Piccirillo, Pruitt, and Reger, 2022). Furthermore, 90 percent of veterans who died by suicide were not classified as high risk by REACH VET, suggesting the need for additional suicide prevention efforts (Levis et al., 2024; McCarthy et al., 2015).

Veterans receiving caring contacts have increased health care utilization.

Launched at the onset of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, VA‘s Caring Contacts Program has personnel who send brief, periodic messages of support to veterans at elevated risk of suicide. Eligible veterans include those enrolled in VHA psychiatric inpatient programs, callers to the Veterans Crisis Line, veterans with a recent deactivation of a high-risk flag (i.e., a flag that a provider can enter into a patient’s electronic health record according to established criteria; see VA, 2003) in their electronic health records, and those identified by REACH VET (Landes, Jegley, and Dollar, 2024). In general, caring contacts are well received by many veterans (Chalker et al., 2024; Landes et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2023). In a randomized clinical trial implemented among callers to the Veterans Crisis Line, those enrolled in the Caring Contacts program were more likely to use health care subsequently. However, the trial had no effect on future suicide attempts (Reger et al., 2024). Implementation studies suggest that caring contacts do not reach veterans without mailing addresses, including those with unstable housing and, therefore, miss reaching some veterans at heightened suicide risk (VHA patients with a homeless indicator in their electronic health records have had elevated rates of suicide since 2001) (Landes et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2023; Office of Suicide Prevention, 2024b).

Multiple VA efforts aim to prevent suicide by firearms.

There is compelling evidence to suggest that putting time and space between individuals who have thoughts of suicide and the means that people use to take their lives is an effective suicide prevention strategy. Such strategies include putting barriers on bridges to prevent jumping, using blister packaging for medications to prevent overdoses, and making ligature-resistant structures to prevent hangings (Azrael and Miller, 2016). Because firearms are the leading method used among veterans who die by suicide, VA has begun developing programs encouraging veterans to store their firearms securely, including a free cable lock distribution program for interested veterans and creating and maintaining KeepItSecure.net, which provides educational resources on secure firearm storage and additional resources (Office of Suicide Prevention, 2024a).

VA-supported researchers are also developing and testing new approaches to promote secure firearm storage. Peer Engagement and Exploration of Responsibility and Safety (PEERS) is a peer-delivered intervention program that promotes lethal means safety to firearm-owning veterans (Houtsma et al., 2025). In 2024, VA launched a pilot Firearm Lockbox Program that offers gun lockboxes at no charge to high-risk veterans who are willing to receive such storage devices (Sprey, 2024). VA researchers also continue to test new public messaging strategies (see, for example, Berger et al., 2024; and Karras et al., 2019). Although there is early-stage evidence about the acceptability or feasibility of these efforts (Berger et al., 2024; Houtsma et al., 2024; Landes et al., 2024; Valenstein et al., 2018), there is, as of this writing, no evidence that that these initiatives reduce veteran suicide or change the way that veterans store their firearms.

Community-based efforts are creating localized efforts to prevent veteran suicide.

VA has partnered with the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) to implement the Governor’s and Mayor’s Challenges to Prevent Suicide Among Service Members, Veterans, and Their Families. This effort provides resources and training for multicomponent state and city community interventions, as highlighted in the Clinical Practice Guidelines for Suicide Prevention and guided by VA‘s Community-Based Interventions for Suicide Prevention model (SAMHSA, 2024). This approach allows state teams to use different strategies at various levels according to the resources that they have available. The Staff Sergeant Parker Gordon Fox Suicide Prevention Grant Program, legislated by Congress and administered by VA, is a grant program that authorizes the distribution of $174 million to provide resources to community-based organizations to administer veteran suicide prevention programs. This program has funded 91 organizations that primarily offered trainings, raised awareness, sent mailings, built coalitions, or engaged in other media or marketing efforts (VA, 2024b). VA has also employed community engagement and partnership coordinators to work in communities to develop and support local coalitions to prevent veteran suicide through six priority areas: identify servicemembers, veterans, and their families; screen for suicide; promote connectedness; improve care transitions; increase lethal means safety; and plan for safety (Mackowiak et al., 2025). Although other similar community-based approaches have been evaluated and found to be effective (see, for example, Goldston and Walrath, 2023), outcome data from these VA efforts are not yet available.

Nongovernmental efforts to prevent veteran suicide are expanding and have mixed evidence.

Outside VA, nonprofit and private entities offer services to prevent veteran suicide. In some cases, these efforts augment the behavioral health services provided by VA to veterans who are not engaged in VHA care. In other instances, companies and organizations offer unique services, including retreats, performing arts courses, and therapies that are not offered by VA (e.g., stellate ganglion block, hyperbaric oxygen, equine therapy). Face the Fight, launched in 2023, is a coalition of corporations, foundations, nonprofits, and veteran-focused organizations that raises awareness of and support for veteran suicide prevention (Ramchand et al., 2025).

VA has partnered with some of these organizations formally. For example, in 2022, VA launched Mission Daybreak, which awarded funds to ten organizations to develop novel veteran suicide prevention solutions (VA, 2023). As described in a 2025 RAND publication, evidence for the effects of types of efforts at reducing suicide is mixed (Ramchand et al., 2025).

Directions for Future Research

Researchers are engaged in multiple efforts to address veteran suicide, and many studies are ongoing. There remains much to explore to better understand why veterans die by suicide and how policies, practices and programs can contribute to effective suicide prevention and intervention.

- Research is needed on how to reach and effectively address veterans at risk for suicide in ways that are not connected to VA. Although VA has implemented various suicide prevention strategies, not all veterans are eligible or opt to receive care through VA. Among the veterans who died by suicide in 2022, 60 percent did not have an encounter with VHA in the year of their death or the prior year, and 40 percent had no contact with VHA (including never having enrolled in VHA and receiving benefits from the Veterans Benefits Administration).

- Research needs to create and test tailored suicide prevention strategies for subpopulations of veterans at increased risk for suicide. Several subgroups of veterans have increased risk of suicide, including those who experienced MST, those who recently separated from military service, and those who received OTH discharges. There are other groups of veterans at increased risk, and many veterans fall into more than one group.

- Research is needed to test which social and economic policies would reduce suicide risk among veterans and whether directly addressing veterans’ economic circumstances might lead to reductions in suicide. Veterans who have limited economic resources are a group at increased risk of suicide. Emerging literature suggests that economic conditions affect suicide risk (Ramchand et al., forthcoming) and that social and economic policies could reduce veteran suicide (Purtle et al., 2025).

- Research is needed to analyze the effectiveness of the existing community-based programs that are meant to prevent veteran suicide. There are community-based approaches to preventing suicide being implemented across the United States, but, as of this writing, there is little information about how effective these efforts are at preventing veteran suicide.

- There is a need for more research on novel strategies to prevent suicide to increase the suite of available effective, evidence-based approaches. VA is conducting research on how new therapies, including pharmacological approaches involving ketamine or psychedelics, might address suicide risk. In addition, there are novel approaches for monitoring risk and delivering treatments, including just-in-time adaptive interventions that use information provided by monitoring devices in real time to identify when people are at risk of suicide and deliver treatment at that moment (Coppersmith et al., 2022).

– Rajeev Ramchand, Tahina Montoya, Published courtesy of RAND.