Researchers from the Quadram Institute and University of East Anglia have identified what makes some strains of gut bacteria life-threatening in pre-term babies.

The findings will help identify and track dangerous strains and protect vulnerable neonatal babies.

A major threat to neonatal babies with extremely low birth weight is necrotising enterocolitis (NEC).

Rare in full term babies, this microbial infection exploits vulnerabilities destroying gut tissue leading to severe complications. Two out of five cases are fatal.

One bacterial species that causes especially sudden and severe disease is Clostridium perfringens. These are common in the environment and non-disease-causing strains live in healthy human guts.

So what makes certain strains so dangerous in preterm babies?

Prof Lindsay Hall and Dr. Raymond Kiu from the Quadram Institute and UEA led the first major study on C. perfringens genomes from preterm babies, including some babies with necrotising enterocolitis.

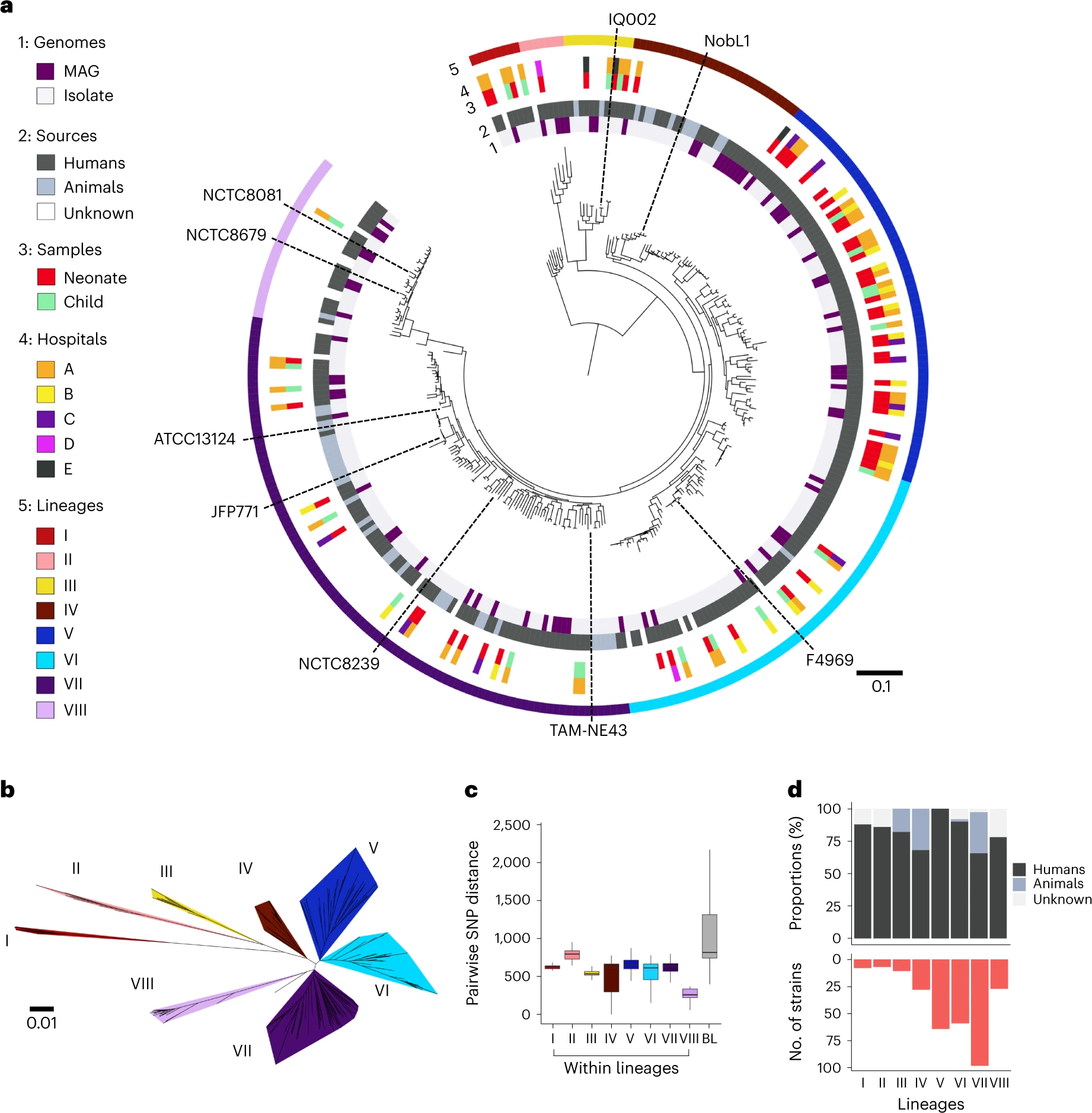

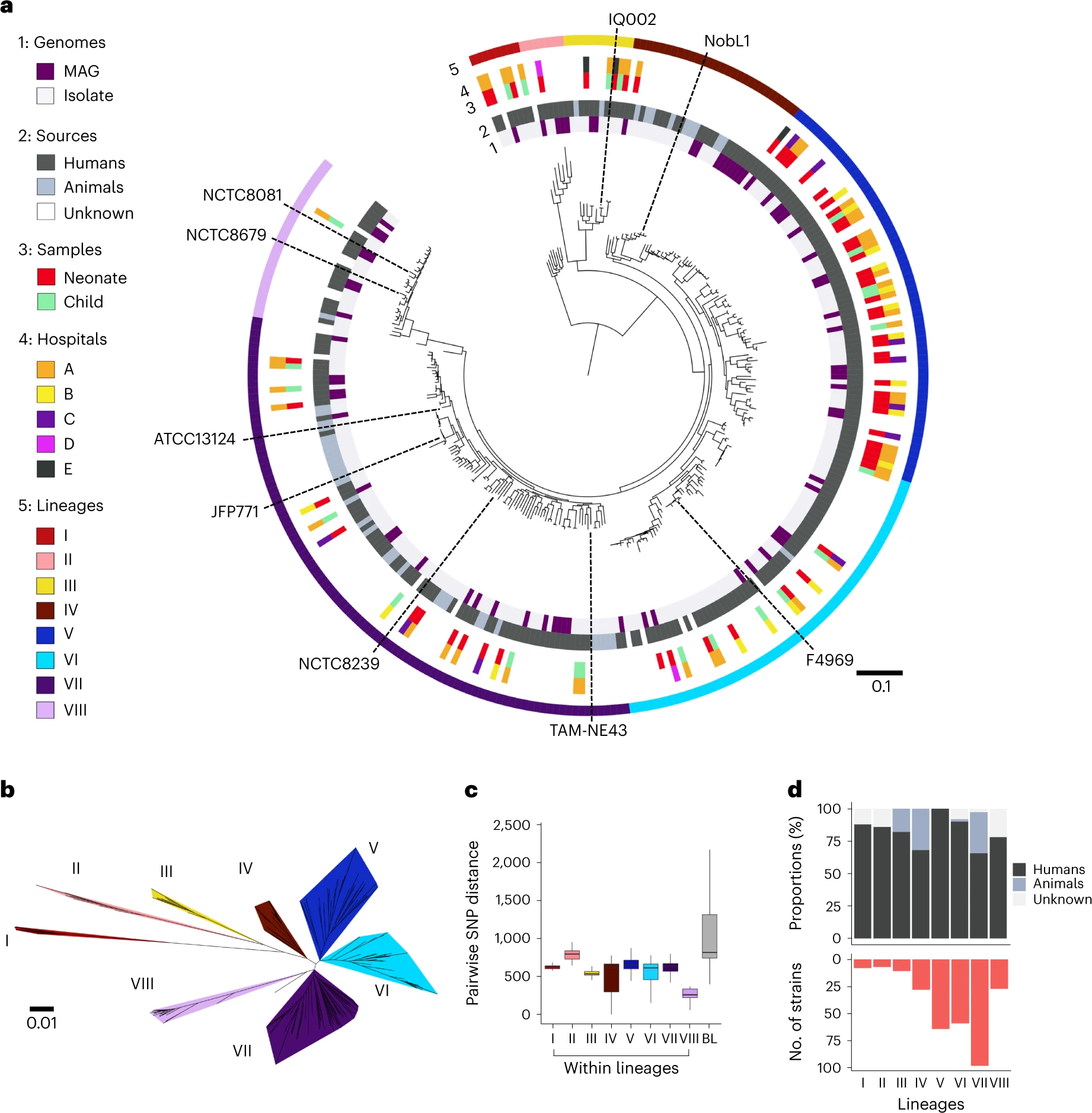

The research team analysed C. perfringens genomes from the faecal samples of 70 babies admitted to five UK Neonatal Intensive Care Units (NICUs).

Based on genomic similarities, they found one set had a lower capacity to cause disease. This allowed a comparison with the more virulent strains.

The less virulent group lacked genes responsible for production of a toxin called PFO and other factors needed for colonisation and survival.

This study has begun to construct genomic signatures for C. perfringens associated with healthy preterm babies and those with necrotising enterocolitis.

Prof Lindsay Hall, from UEA’s Norwich Medical School and the Quadram Institute, said: “Exploring genomic signatures from hundreds of Clostridium perfringens genomes has allowed us potentially to discriminate between ‘good’ bacterial strains that live harmlessly in the preterm gut, and ‘bad’ ones associated with the devastating and deadly disease necrotising enterocolitis.

“We hope the findings will help with ‘tracking’ deadly C. perfringens strains in a very vulnerable group of patients – preterm babies.”

Larger studies, across more sites and with more samples may be needed but this research could help identify better ways to control necrotising enterocolitis.

The team previously worked alongside Prof Paul Clarke and clinical colleagues at the Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital NICU. And they demonstrated the benefits of providing neonatal babies with probiotic supplements.

The enterocolitis gut microbiome of neonatal infants is significantly disrupted, making it susceptible to C. perfringens overgrowth.

Prof Hall said: “Our genomic study gives us more data that we can use in the fight against bacteria that cause disease in babies – where we are harnessing the benefits of another microbial resident, Bifidobacterium, to provide at-risk babies with the best possible start in life.”

Dr. Raymond Kiu, from the Quadram Institute, said: “Importantly, this study highlights Whole Genome Sequencing as a powerful tool for identifying new bacterial lineages and determining bacterial virulence factors at strain level which enables us to better understand disease.”

This research was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, part of UKRI, and the Wellcome Trust.