What’s in a name? A lot, actually.

For the scientific community, names and labels help organize the world’s organisms so they can be identified, studied, and regulated. But for bacteria, there has never been a reliable method to cohesively organize them into species and strains. It’s a problem, because bacteria are one of the most prevalent life forms, making up roughly 75% of all living species on Earth.

An international research team sought to overcome this challenge, which has long plagued scientists who study bacteria. Kostas Konstantinidis, Richard C. Tucker Professor in the School of Civil and Environmental Engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology, co-led a study to investigate natural divisions in bacteria with a goal of determining a scientifically viable method for organizing them into species and strains. To do this, the researchers let the data show them the way.

Their research was published in the journal Nature Communications.

“While there is a working definition for species and strains, this is far from widely accepted in the scientific community,” Konstantinidis said. “This is because those classifications are based on humans’ standards that do not necessarily translate well to the patterns we see in the natural environment.”

For instance, he said, “If we were to classify primates using the same standards that are used to classify E. coli, then all primates — from lemurs to humans to chimpanzees — would belong to a single species.”

There are many reasons why a comprehensive organizing system has been hard to devise, but it often comes down to who gets the most attention and why. More scientific attention generally leads to those bacteria becoming more narrowly defined. For example, bacteria species that contain toxic strains have been extensively studied because of their associations with disease and health. This has been out of the necessity to differentiate harmful strains from harmless ones. Recent discoveries have shown, however, that even defining types of bacteria by their toxicity is unreliable.

“Despite the obvious, cornerstone importance of the concepts of species and strains for microbiology, these remain, nonetheless, ill-defined and confusing,” Konstantinidis said.

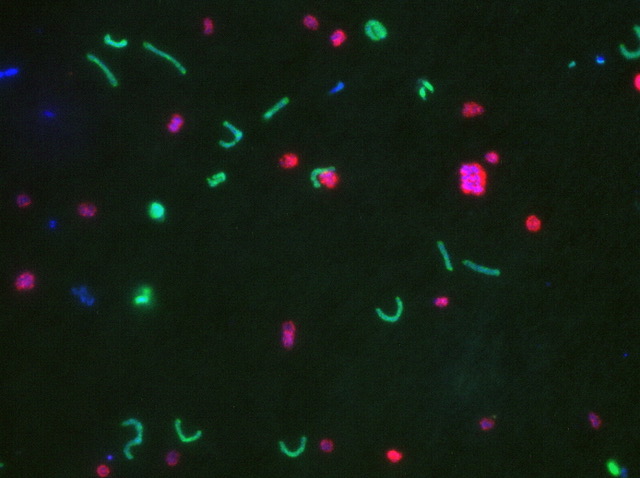

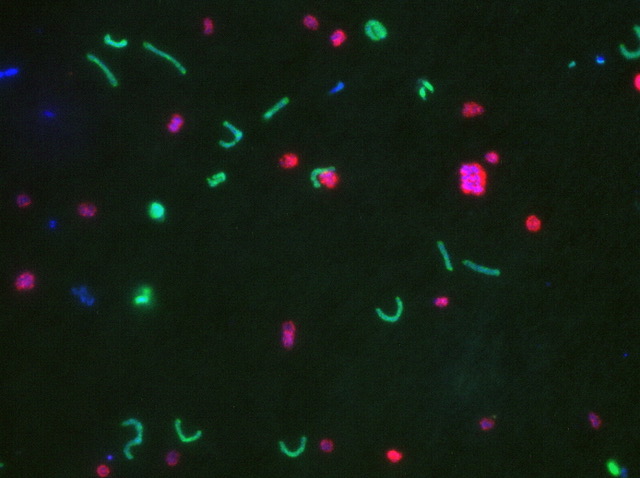

The research team collected bacteria from two salterns in Spain. Salterns are built structures in which seawater evaporates to form salt for consumption. They harbor diverse communities of microorganisms and are ideal locations to study bacteria in their natural environment. This is important for understanding diversity in populations because bacteria often undergo genetic changes when exposed in lab environments.

The team recovered and sequenced 138 random isolates of Salinibacter ruber bacteria from these salterns. To identify natural gaps in genetic diversity, the researchers then compared the isolates against themselves using a measurement known as average nucleotide identity (ANI) — a concept Konstantinidis developed early in his career. ANI is a robust measure of relatedness between any two genomes and is used to study relatedness among microorganisms and viruses, as well as animals. For instance, the ANI between humans and chimpanzees is about 98.7%.

The analysis confirmed the team’s previous observations that microbial species do exist and could be reliably described using ANI. They found that members of the same species of bacteria showed genetic relatedness typically ranging from 96 to 100% on the ANI scale, and generally less than 85% relatedness with members of other species.

The data revealed a natural gap in ANI values around 99.5% ANI within the Salinibacter ruber species that could be used to differentiate the species into its various strains. In a companion paper published in mBio, the flagship journal of the American Society for Microbiology, the team examined about 300 additional bacterial species based on 18,000 genomes that had been recently sequenced and become available in public databases. They observed similar diversity patterns in more than 95% of the species.

“We think this work expands the molecular toolbox for accurately describing important units of diversity at the species level and within species, and we believe it will benefit future microdiversity studies across clinical and environmental settings,” Konstantinidis said.

The team expects their research will be of interest to any professional working with bacteria, including evolutionary biologists, taxonomists, ecologists, environmental engineers, clinicians, bioinformaticians, regulatory agencies, and others. It is available online through Konstantinidis’ website and GitHub to facilitate access and use by scientific and regulatory communities.

“We hope that these communities will embrace the new results and methodologies for the more robust and reliable identification of species and strains they offer, compared to the current practice,” Konstantinidis said.