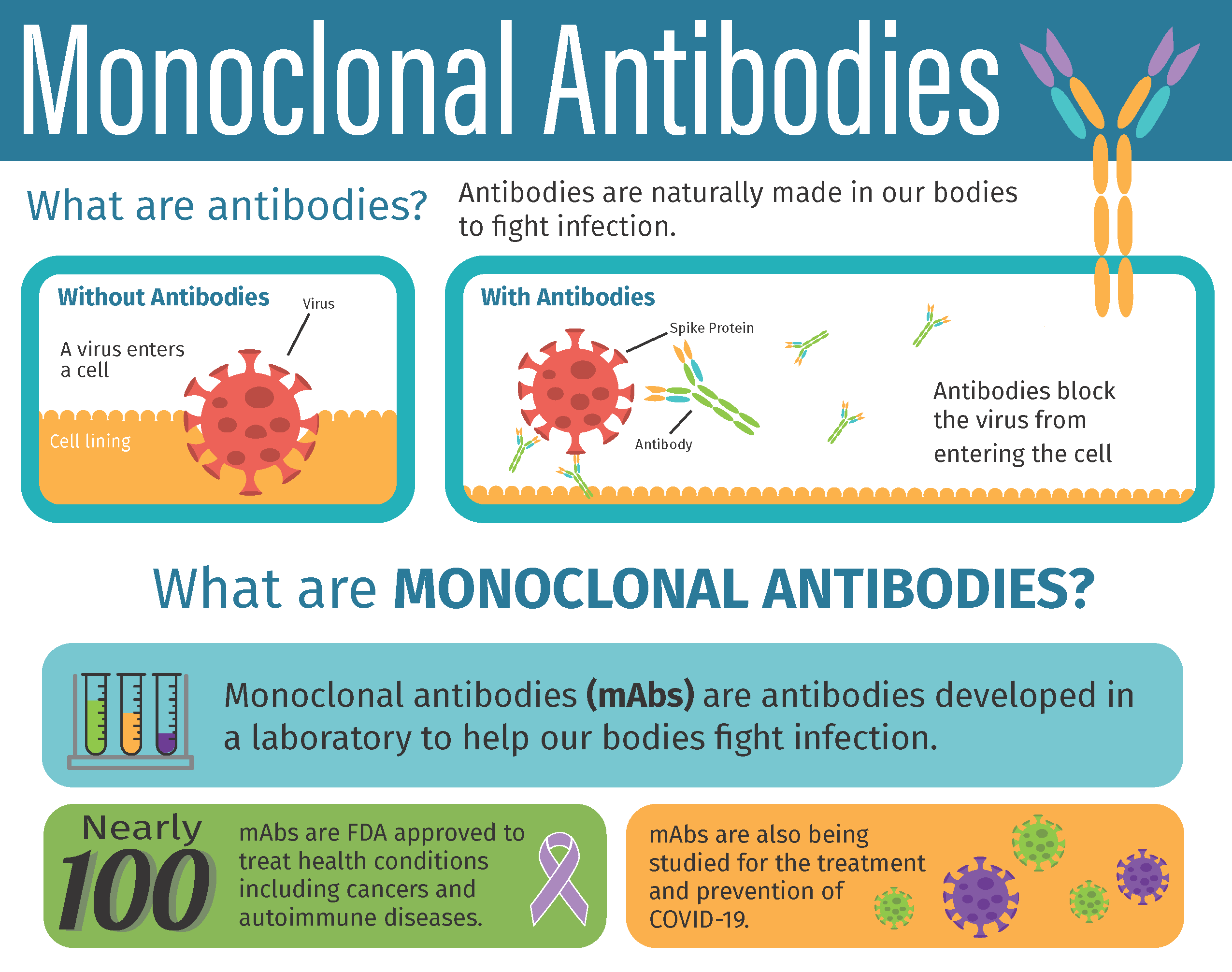

Eighteen months into the pandemic, monoclonal antibodies remain the only FDA-authorized outpatient treatment for patients with symptomatic COVID-19. Laboratory-made proteins that mimic the immune system’s ability to target and block the virus that causes COVID-19 from infecting human cells, monoclonal antibodies have been shown to reduce the risk of the most severe symptoms of COVID-19 and of being admitted to the hospital. While the federal government has distributed over one million antibody treatments to states, prior anecdotal reports suggested they may have been underutilized.

A new analysis by a team of physician-researchers at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine, provides the first evidence that monoclonal antibodies were indeed underutilized in the first six months of FDA authorization. The team examined outpatient medical claims from a national database covering more than 200 million patients in the United States between November 2020 – when monoclonal antibodies were granted emergency use authorization by the FDA – and April 2021.

“During our study period, more than 20 million Americans were diagnosed with COVID-19, yet we found that fewer than 70,000 patients received monoclonal antibody treatments out of a study base encompassing over 60 percent of Americans,” said corresponding author Timothy S. Anderson, MD, MAS, a clinician-investigator and assistant professor medicine in the Division of General Medicine at BIDMC. “These medications were authorized on the cusp of the largest surge of COVID-19 hospitalizations and the initial stages of vaccine rollout, so health systems may not have had capacity to launch monoclonal antibody clinics immediately. However, we expected to see continued growth in their use over time and were surprised to find a sharp decline in monoclonal antibody use throughout early 2021.”

Although additional research is needed to explore the factors that may have contributed to the low initial uptake of monoclonal antibodies, Anderson and colleagues speculate that they may include stockpiling of allocated treatments; limited distribution by health systems; barriers to patient access to treatments which require IV infusion; or hesitancy to adopt new treatments by providers and/or patients. The researchers also observed demographic and insurer differences in antibody use that suggest possible disparities in access; for example, while Medicare recipients made up 10 percent of the research population, they comprised only three percent of patients who received monoclonal antibodies.

“Many patients receive COVID-19 testing through school, workplace and sites outside the healthcare system, and these sites may not be equipped to refer patients to receive monoclonal antibody treatments, particularly if patients do not already have an existing relationship with a healthcare provider,” added Anderson. “The public interest would be well-served by improved transparency on the use of monoclonal antibodies, as has been done with vaccine administration, including the data necessary to ensure equitable access to potentially life-saving treatments.”

The study was conducted through the use of insurance claims data from the COVID-19 Research Database Consortium, which covers 200 million adults but does not capture treatments administered to other patients, including those receiving care through the Department of Veterans Affairs and other federal health settings, or treatments provided free of charge.