Vaccine hesitancy is just one reason fewer people in some parts of the United States have been inoculated against coronavirus.

A study in the journal Lancet Regional Health found that wide disparities in health care coverage, particularly in rural areas, hampered vaccination efforts during the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings point to a hidden divide in America between those with ready geographic and financial access to doctors, hospitals and clinics and those without.

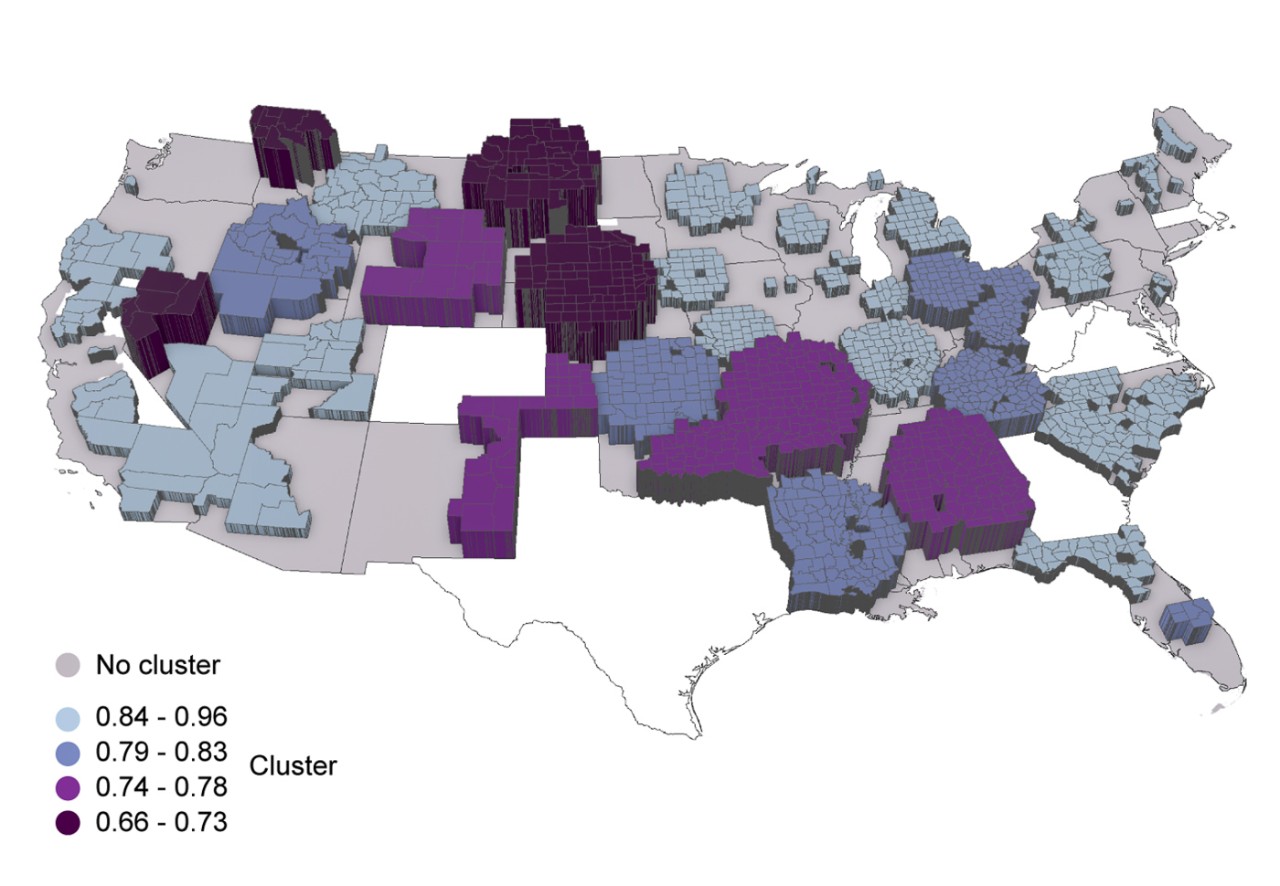

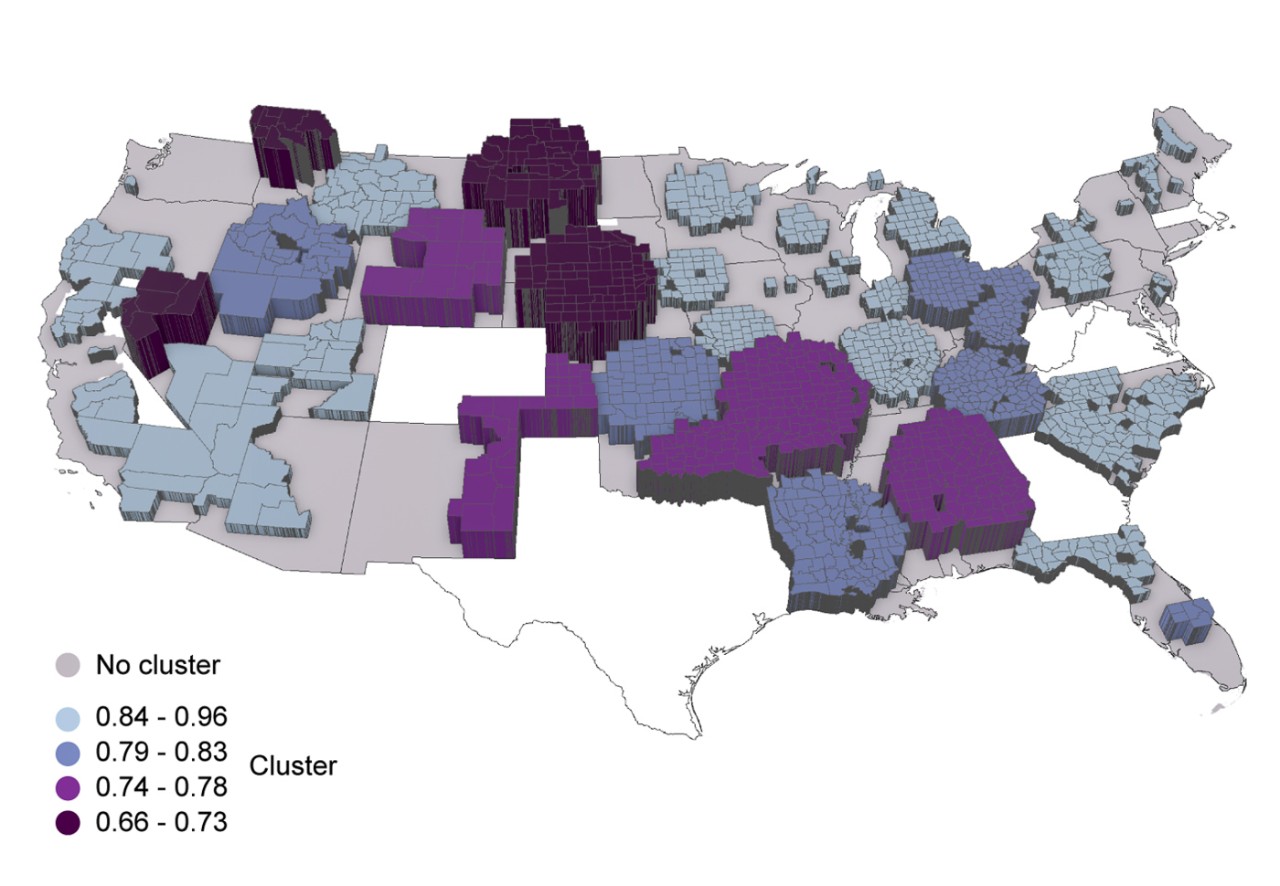

University of Cincinnati epidemiologist Diego Cuadros led an international team of researchers investigating disparities in vaccination rates across 2,417 U.S. counties. They found that the availability of health care resources influences vaccine coverage.

The pandemic has killed more than 6.3 million people worldwide, including more than 1 million people in the United States alone. When it comes to the country’s comparatively high rate of mortality, researchers point to failures of vaccination compared to other countries.

Cuadros, an associate professor of geography in UC’s College of Arts and Sciences, said the rate of vaccination varies widely across the United States. While some people may be reluctant to get vaccinated because of unfounded fears or misinformation, that tells only part of the story, he said.

“During the pandemic we realized the huge health care disparity we have in this country,” he said.

Barriers to health care access include cost, insurance coverage and transportation.

In national surveys, about 20% of the U.S. population has reported an unwillingness to be vaccinated. This does not account for the larger unvaccinated population. While more than half of the population in every U.S. state is now fully vaccinated, some states are much further ahead than others.

Cuadros said areas with low vaccination saw the highest rates of mortality from the virus during the delta and omicron waves, demonstrating the terrible impact that health disparities can have on underserved communities.

Co-author Neil MacKinnon, provost for Augusta University in Georgia, said the pandemic caused enormous disruptions to health care services even in places with ready access. People saw their doctors much less frequently, leading to more undiagnosed cases of cancer and other diseases.

“Our study demonstrates that these disruptions were not uniform across the United States,” MacKinnon said. “Many counties, especially those in rural areas, experienced significant disruptions in health care, including the distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine itself.”

The new analysis found that people in underserved communities were as much as 34% less likely to be vaccinated against COVID-19. These included counties in Nevada, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota and Nebraska where vaccination rates were lowest.

“America’s healthcare system has improvements to be made to address historical disparities that, as shown in our study, can influence individual-level decision-making,” study co-author and UC geography student Santiago Escobar said. “Our study suggests clear disparities that need to be addressed.”

Co-author Phillip Coule, M.D., chief medical officer for Augusta University Health in Georgia, said the study underscores the impact of vaccination in fighting diseases like COVID-19.

“Those responsible for guiding health policy need to consider issues such as vaccination rates, access to care and health disparities when evaluating outcomes from COVID-19 and other conditions,” he said.