A simple and sensitive urine test developed by Imperial and MIT engineers has produced a colour change in urine to signal growing tumours in mice.

Tools that detect cancer in its early stages can increase patient survival and quality of life. However, cancer screening approaches often call for expensive equipment and trips to the clinic, which may not be feasible in rural or developing areas with little medical infrastructure. The emerging field of point-of-care diagnostics is therefore working on cheaper, faster, and easier-to-use tests.

An international pair of engineering labs have now developed a tool that changes the colour of mouse urine when colon cancer is present. The findings from testing the fast, non-invasive cancer test are published in Nature Nanotechnology.

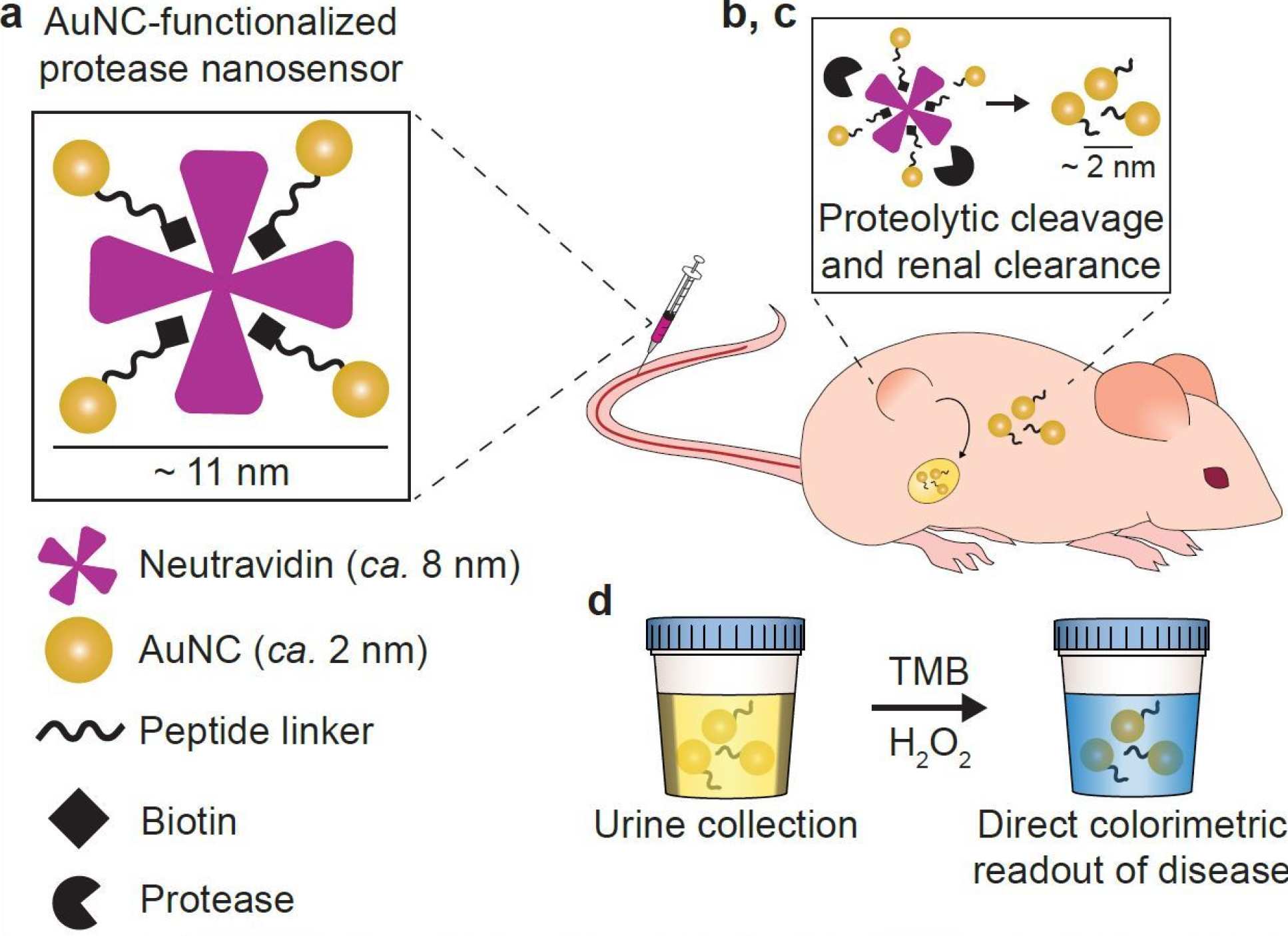

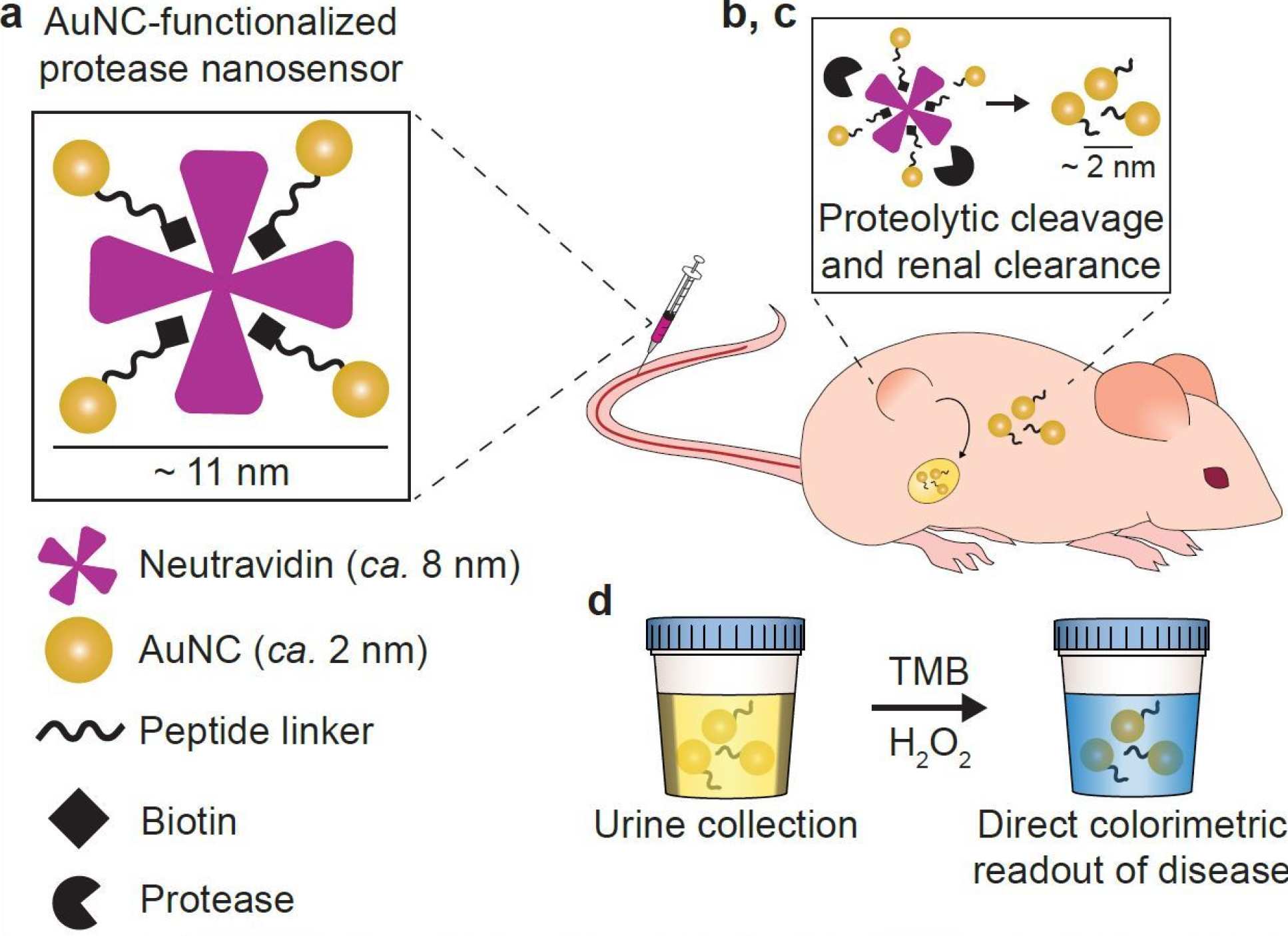

The early stage technology, developed by teams led by Imperial’s Professor Molly Stevens and MIT professor and Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator Sangeeta Bhatia, works by injecting nanosensors into mice, which are cut up by enzymes released by the tumour, known as proteases.

When the nanosensors are broken up by proteases, they pass through the kidney, and can be seen with the naked eye after a urine test that produces a blue colour change.

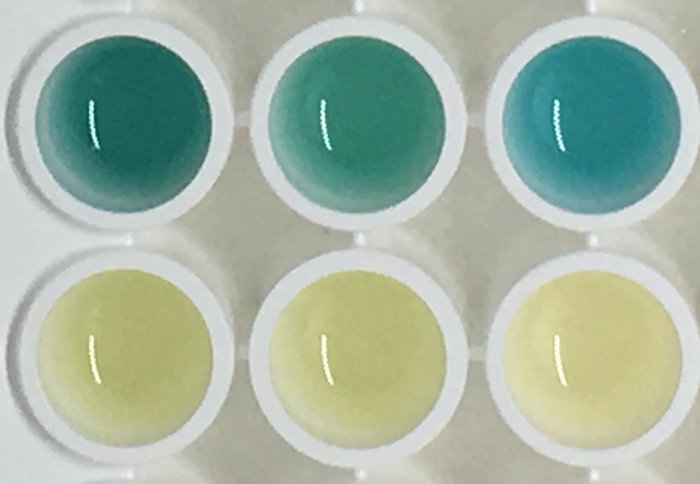

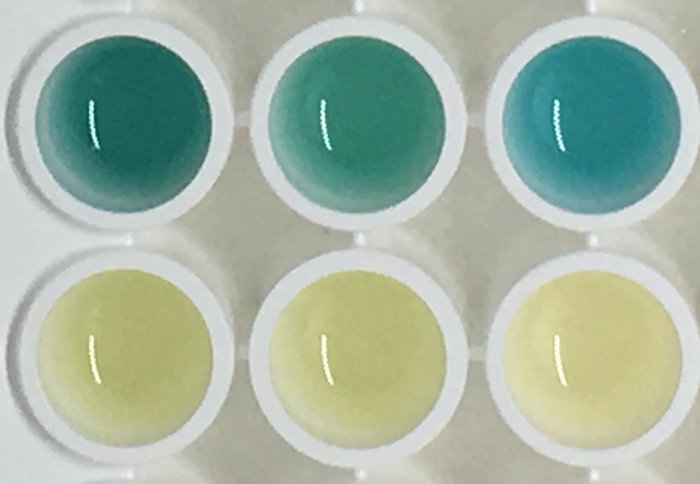

The researchers applied this technology to mice with colon cancer, and found that urine from tumour-bearing mice becomes bright blue, relative to test samples taken from healthy mice.

Professor Stevens, of Imperial’s Departments of Materials and Bioengineering, said: “By taking advantage of a chemical reaction that produces a colour change, this test can be administered without the need for expensive and hard-to-use lab instruments.

“The simple readout could potentially be captured by a smartphone picture and transmitted to remote caregivers to connect patients to treatment.”

Sensing signals

When tumours grow and spread, they often produce biological signals known as biomarkers that clinicians use to both detect and track disease. However, not all biomarkers play an active role in tumour growth, and most are present in such small quantities that they can be challenging to find.

One family of tumour proteins known as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) have attracted attention as potential biomarkers, since these enzymes help promote the growth and spread of tumours by chewing up the tissue scaffolds that normally keep cells in place.

Many cancer types, including colon tumours, produce high levels of several MMP enzymes, including one called MMP9.

In this study, the Imperial-MIT team developed nanosensors where ultra-small gold nanoclusters (AuNCs) were connected to a protein carrier through linkages that are broken by MMP9s

To develop the colour-changing urine test, the researchers used two AuNC properties – their very small (<2 nanometre) size, and their ability to cause a blue colour change when treated with a chemical substrate and hydrogen peroxide.

The researchers designed the AuNC-protein complexes to disassemble after being cut by MMPs in the tumour microenvironment or blood. When broken apart, the released AuNCs travel via the blood and are small enough to be filtered through the kidneys into the urine.

In healthy mice without high MMP levels, the complexes remain intact, and are too large to pass into the urine. If AuNCs have been concentrated in the urine, a chemical test will produce a blue colour change that is visible with the naked eye.

For this study, the researchers developed sensors that are cut apart by particular MMPs and tested them in mice. The researchers demonstrated that their colour change test could accurately detect which urine samples came from mice with colon tumours in a study of 28 mice injected with the sensors, where 14 mice were healthy and 14 had tumours.

Within half an hour of the chemical treatment, only the urine from mice with colon tumours had a strong blue colour. By contrast, urine from the healthy control mice exhibited no colour change.

The team also designed the AuNC surfaces to go ‘unseen’ by the immune system to prevent immune reactions or toxic side effects, and to prevent abundant serum proteins from sticking to them, which would make the nanosensors too large to be filtered by the kidneys.

During a four-week follow up after nanosensor administration, the mice showed no signs of side effects, and there was no evidence that the protein-sensor complex or free AuNCs lingered in the bodies of the mice.

Co-first author Dr Colleen Loynachan, of Imperial’s Department of Materials, said: “The AuNCs are similar to materials already used in the clinic for imaging tumours, but here we are taking advantage of their unique properties to give us additional information about disease. However, there’s still a lot of optimisation and testing needed before the technology can move beyond the lab.”

Accessible diagnostics

Next, the team will work to increase the specificity and sensitivity of the sensors by testing them in additional animal models to investigate diagnostic accuracy and safety.

“Proteases play functional roles in a number of diseases such as cancer, infectious diseases, inflammation, and thrombosis,” said co-first author Ava Soleimany, of Harvard and MIT. “By designing versions of our sensors that can be cut by different proteases, we could apply this colour-based test to detect a diversity of conditions.”

The researchers are now working on a formulation that is easier to administer, and identifying ways to make the sensors responsive to multiple biomarkers in order to distinguish between cancers and other diseases.