Particulate matter (PM) is a major component of air pollution that is increasingly associated with long-term consequences for the health and development of children. In a study recently published in Nature’s Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine, Natalie Johnson, PhD, associate professor at the Texas A&M University School of Public Health, and her co-authors synthesized the findings of previous studies, reviews and meta-analyses on the adverse health effects of the two smallest types of particulate matter (PM): fine (particles with an aerodynamic diameter less than 2.5 μm) and ultrafine (particles with an aerodynamic diameter less than 1 μm). Both types of PM can be inhaled deep into the lung. Ultrafine particles have recently been shown to cross into circulation and even cross the placental barrier, directly reaching the developing fetus.

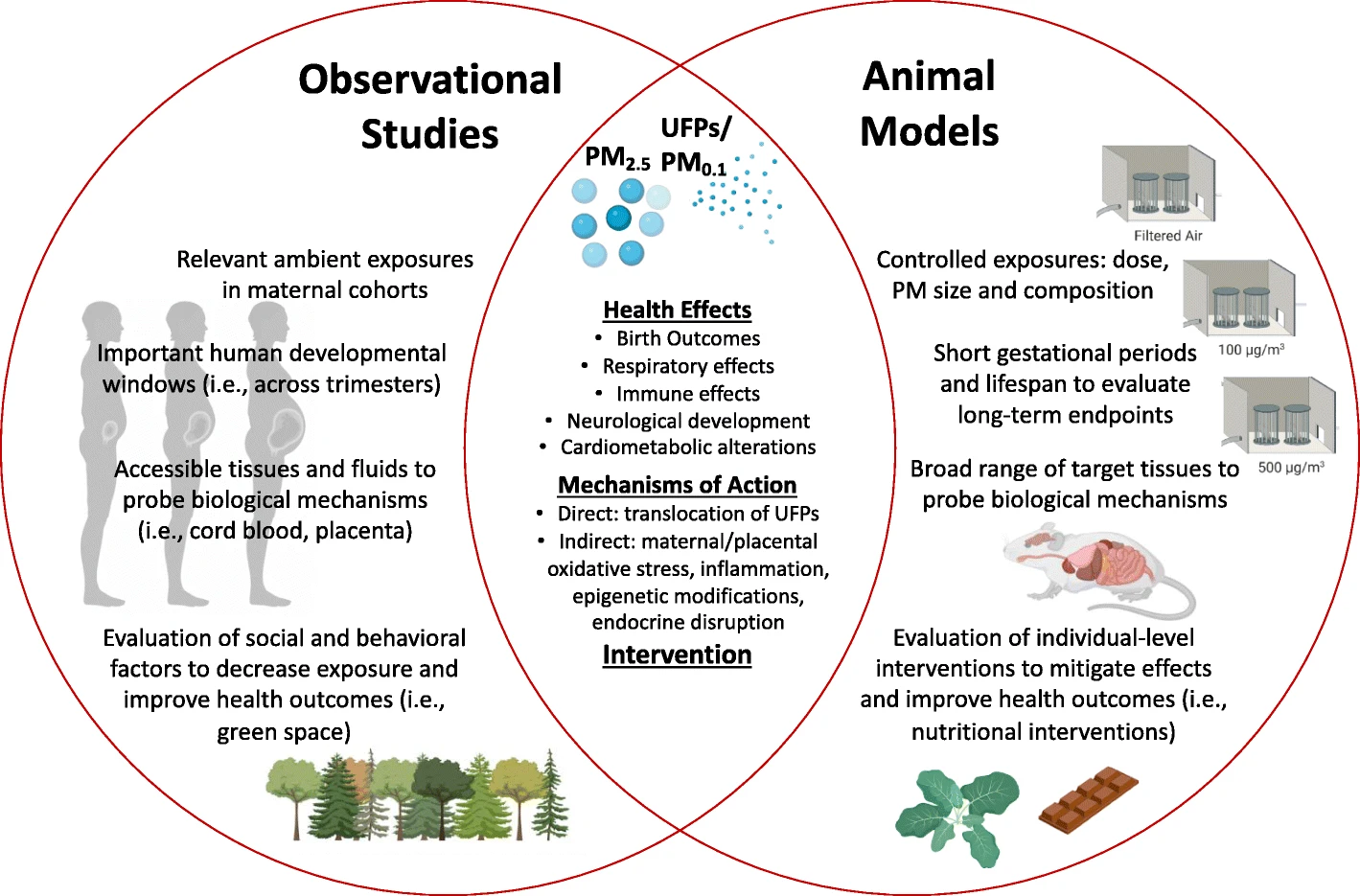

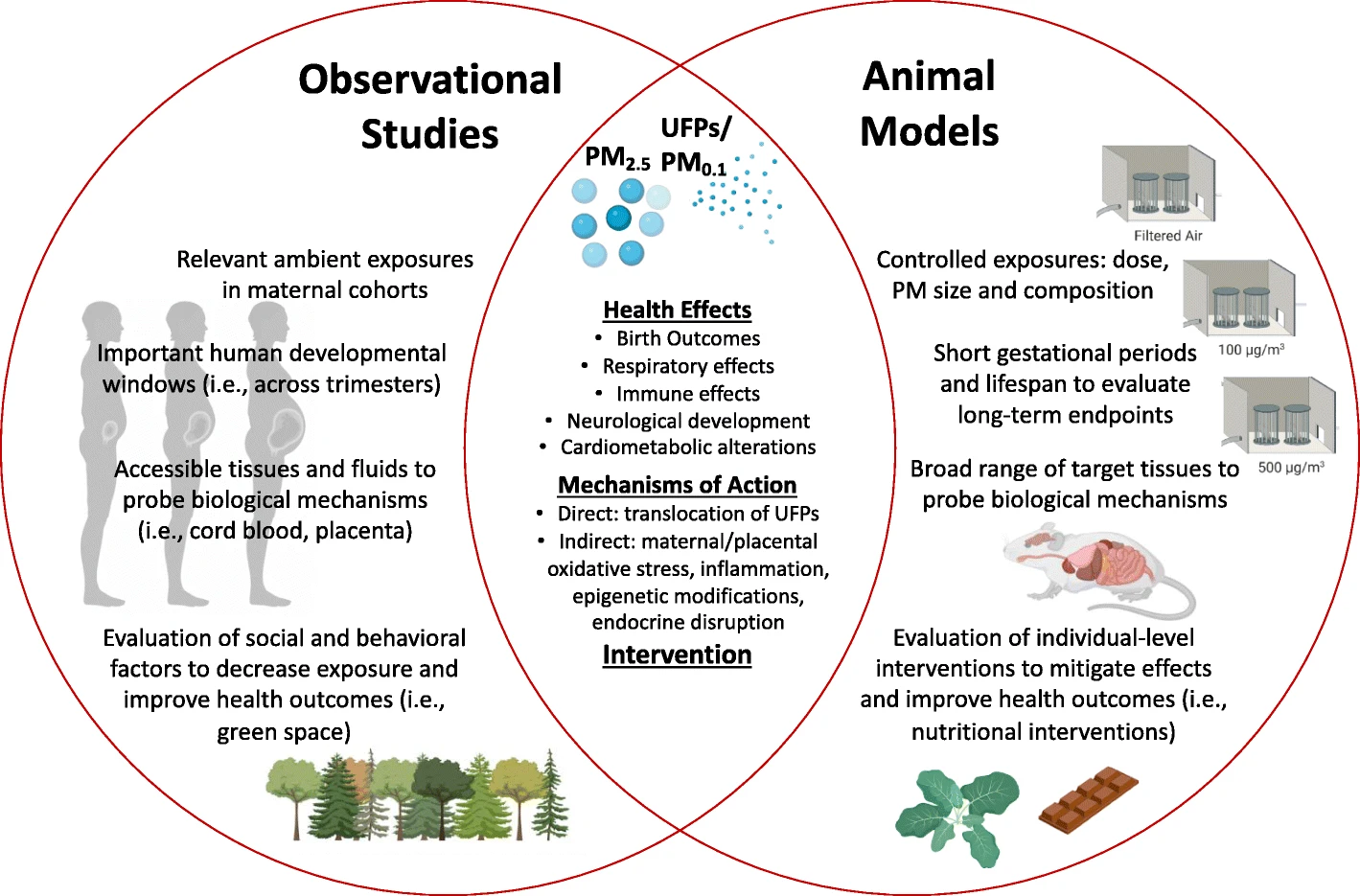

A range of adverse health outcomes associated with fine PM exposure were reported in the studies and reviews of human data, including low birth weight, asthma and other chronic respiratory conditions, cognitive and behavioral issues, obesity and diabetes. Research on the effects of prenatal ultrafine PM exposure has not been as extensive, but a growing body of evidence shows similarities with the effects associated with fine PM exposure. Studies and reviews of data obtained from animal models supported the findings from the human studies.

In addition, some of the studies examined the possible ways that PM could cause the observed adverse health effects. The two broad mechanisms documented in the literature are direct (ultrafine PM crosses the placenta and enters fetal circulation) and indirect (PM causes interactions that result in oxidative stress, inflammation, epigenetic changes and endocrine disruption).

The researchers also reviewed possible treatments and policies that might minimize or even undo the harms associated with prenatal PM exposure. Green spaces such as parks and other areas with trees and foliage provide a range of benefits for the communities that have them, including lower exposure to PM. Nutritional interventions, including maternal dietary changes and antioxidant and vitamin supplementation, can provide protective effects that are also associated with better health outcomes for children with prenatal air pollution exposure.

“It is important to review the body of literature on such an important and common environmental exposure. This helps in policy development and intervention strategies. The timing of exposure, like during pregnancy, is becoming recognized as an important window of susceptibility. So, protecting the most vulnerable can have a huge public health impact,” Johnson said.