A growing number of genomic studies have generated important discoveries regarding human health and behavior, but new research from the University of Oxford suggests that scientific advancement is limited by a lack of diversity. They show that the people studied in genetic discovery research continue to be overwhelmingly of European descent, but also for the first time reveal that subjects are concentrated in a handful of countries – the UK, US and Iceland, and have specific demographic characteristics. The authors caution that this lack of diversity has potentially huge implications for the understanding and applications of genetic discoveries.

The study published in Communications Biology contributes to a richer understanding of a multitude of facets which shape genomic bias over time. The work reviewed nearly 4,000 scientific studies between 2005 and 2018, curated by the NHGRI-EBI GWAS Catalogue, which contains all Genetic-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) to date.

These studies have identified multiple genetic groups related to diseases such as type 2 diabetes, Alzheimer’s, to psychiatric disorders, physical, behavioral and psychological traits. The study examined the explosion in the number of people studied, number and strength of genetic association discoveries, and growth and variation in the number of outcomes (or ‘phenotypes’) studied. It also looked at who was being studied in terms of ancestral background, geographical location and demographics, but also who was conducting the research, including the networks and characteristics of the researchers themselves.

Despite a staggering growth in sample sizes, the number of traits and diseases studied and genetic discoveries, findings from the study reveal that ancestral diversity has stalled and that non-white groups are still massively under-represented.

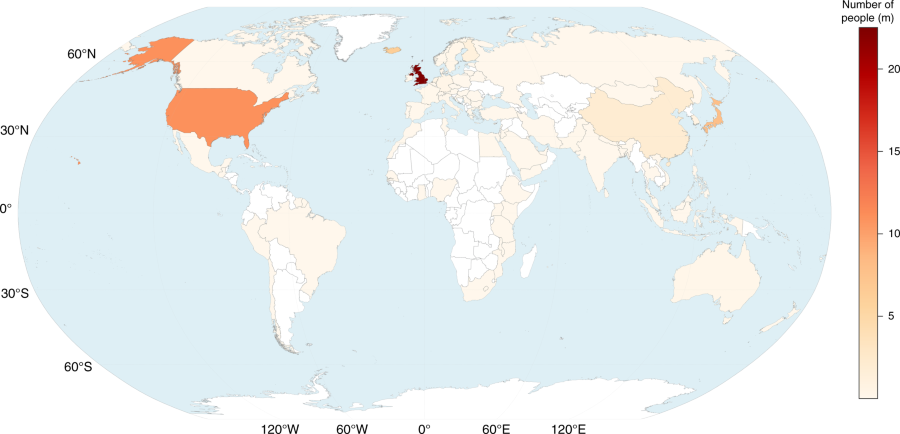

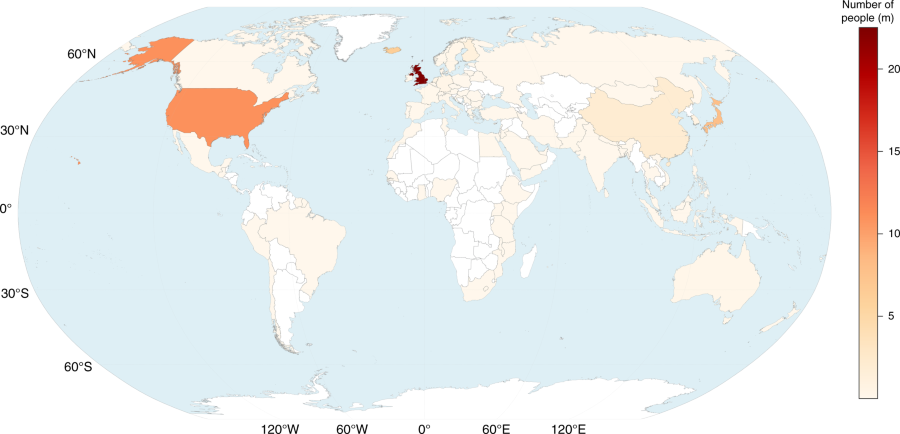

By extending research in this area they show that this has varied considerably over time and that when non-European ancestry groups are included, it is often only to ‘replicate’ results, as opposed to fundamental new genetic discoveries. Moving beyond ancestral diversity, the authors estimate for the first time that 72% of the (often repeatedly) utilized data came from individuals recruited from just three countries; the UK (40%), US (19%) and Iceland (12%). Data was subject not only to geographical concentration, but also featured a higher than anticipated proportion of older people, women and in some of the most prominently used data, also subjects with higher socioeconomic status and better health.

Prof Melinda Mills (MBE FBA), lead author and Nuffield Professor of Sociology, said “the lack of ancestral diversity in genomic research has been an on-going concern, but little attention has been placed on the geographical and demographic characteristics of the people who are studied, who studies them, and exactly what they study. Genetic discoveries offer exciting medical possibilities, but without increasing the diversity of people studied and environments they live in, the usage and returns of this research are limited. There is increasing recognition that our health outcomes are a complex interplay between genes and the environment – or in other words nature and nurture – yet most discoveries have been taken from populations that are very similar, with limited environmental variation.”

The authors also analyzed the core funders of this work (primarily UK and US sources) and revealed gender disparities in scientific authorship, estimating that up to 70 percent of authors in the senior ‘last author’ position are male. They also provide evidence of a tightly knit core network revolving around providers of access to the data, such as researchers working as Principle Investigators of longitudinal cohorts and senior members of large biopharmaceutical companies. They provide a number of core policy recommendations for editors, funders and policy-makers. These include: prioritizing multiple types of diversity and strategies for monitoring diversity, warnings regarding the interpretation of genetic differences between ancestral groups, calls for local participant involvement, and strategies for reforming incentive structures that intertwine the roles of authorship, data ownership and access to results.

Mills further adds that “we were able to harness different types of data and link them together in new ways to empirically demonstrate the inner workings of this important research area for the first time. It is our hope that the ten evidence-based policy recommendations will be taken up in order to further enhance the power of the on-going genomic revolution.”