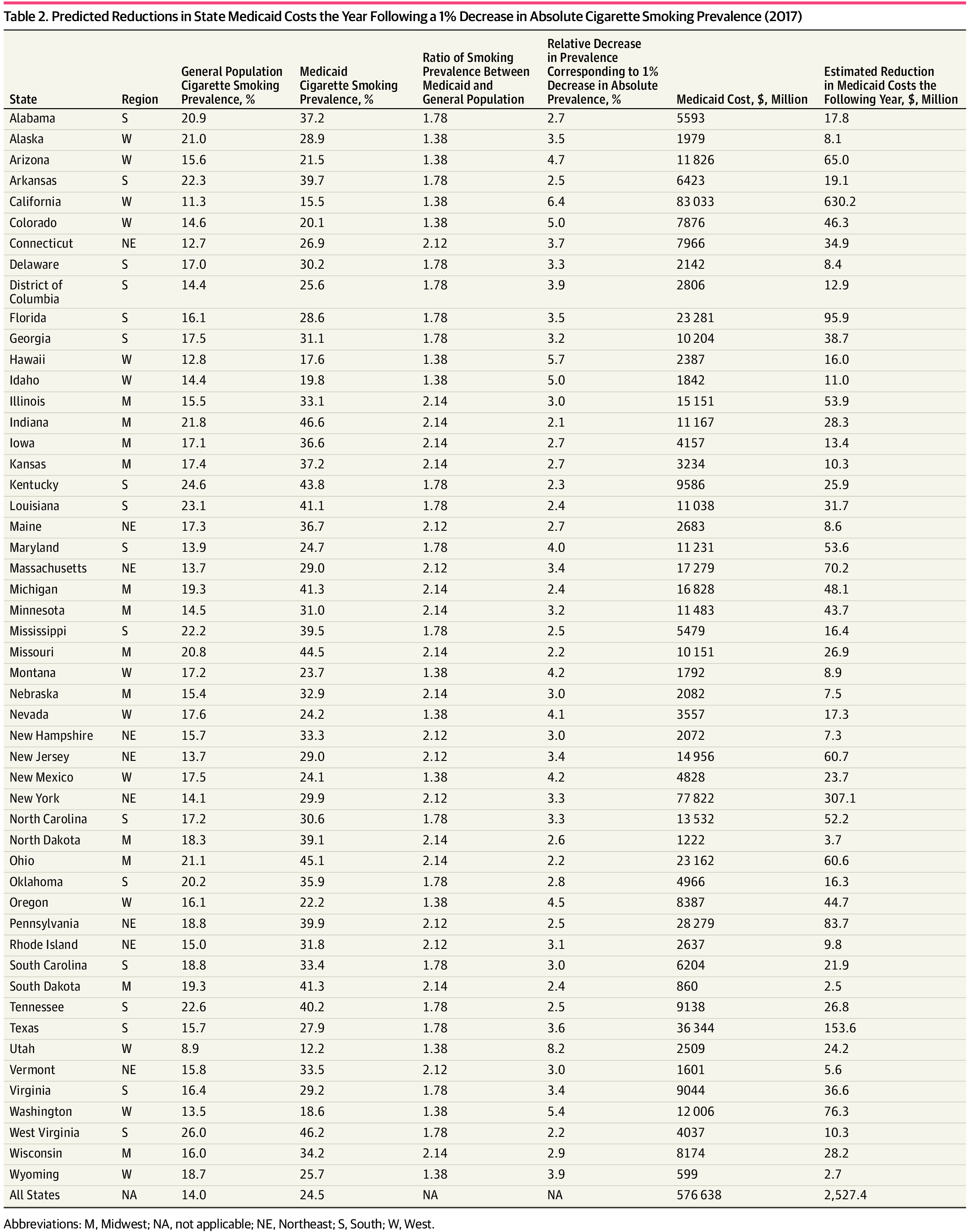

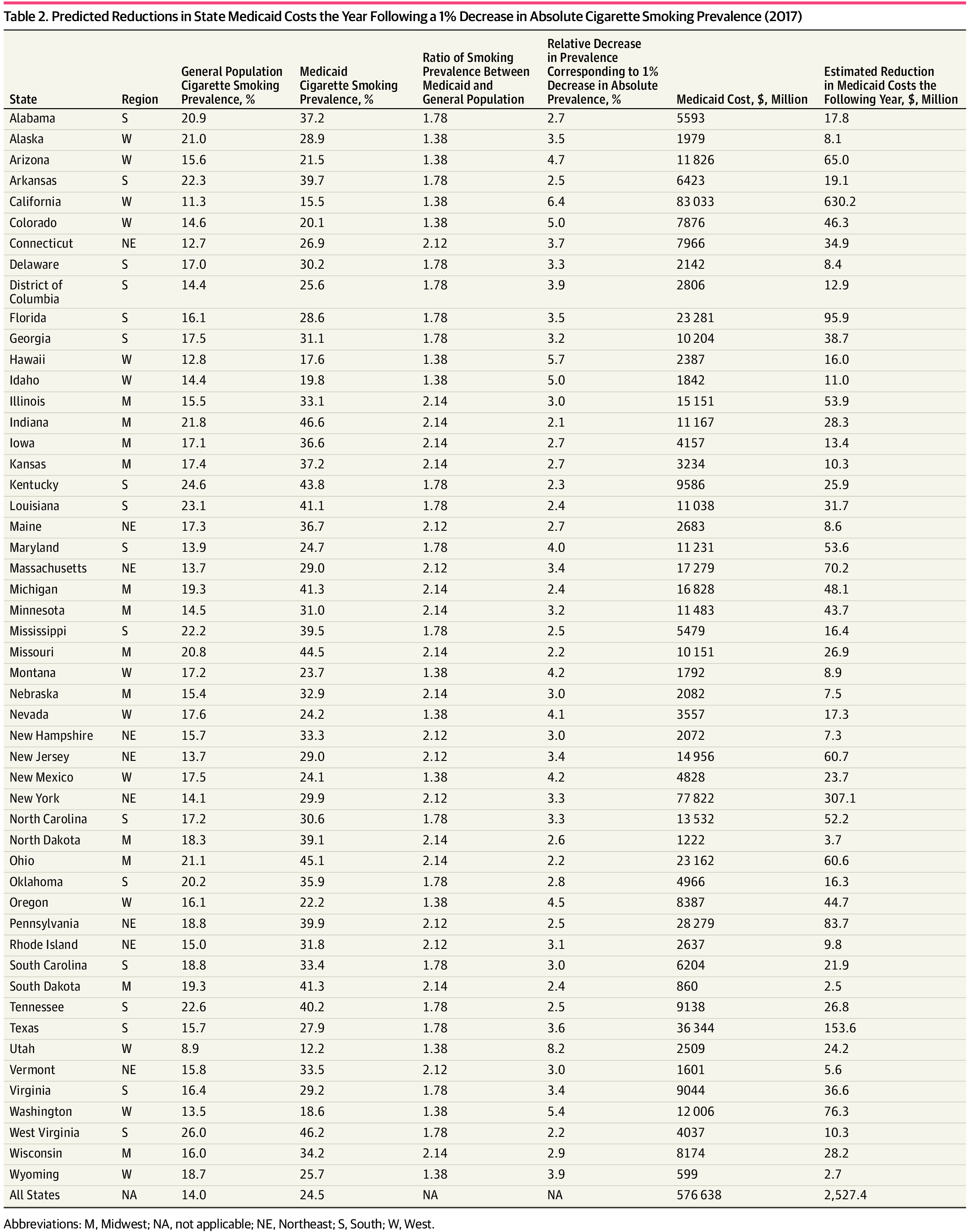

Reducing smoking, and its associated health effects, among Medicaid recipients in each state by just 1 percent would result in $2.6 billion in total Medicaid savings the following year, according to new research by UC San Francisco.

The median state would save $25 million, ranging from $630.2 million in California (if the smoking rate dropped from 15.5 percent to 14.5 percent) to $2.5 million in South Dakota (if the rate dropped from 41.3 to 40.3 percent), the research found.

The study, by Stanton A. Glantz, PhD, director of the UCSF Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education, is published in JAMA Network Open.

“While 14 percent of all adults in the U.S. smoke cigarettes, 24.5 percent of adult Medicaid recipients smoke,” said Glantz. “This suggests that an investment in reducing smoking in this population could be associated with a reduction in Medicaid costs in the short run.”

Total Medicaid costs in 2017 were $577 billion.

“There is no question that reducing smoking is associated with reduced health costs, but it’s commonly assumed that it takes years to see these savings, which has discouraged many states from prioritizing helping smokers quit,” said Glantz.

“While this is true for some diseases, such as cancer, other health risks such as heart attacks, lung disease and pregnancy complications respond quickly to changes in smoking behavior. So reducing the prevalence of smoking would be an excellent short-term investment in the physical health of smokers and the fiscal health of the Medicaid system,” he said.

Glantz derived state-by-state percentages of Medicaid recipients who smoke based on data from the 2017 Behavioral Risk Factors Surveillance System, which provides the percentage of smokers among the population of each state, and the 2017 National Health Interview Survey, which identifies Medicaid recipients in four major regions in the United States (Northeast, Midwest, South and West).

He then estimated potential Medicaid savings based on a previous research finding which showed that a 1 percent relative reduction in smoking prevalence is associated with a reduction of 0.118 percent in per capita health care spending.

Glantz noted that the study looked only at the potential savings from reducing the total number of Medicaid recipients who smoke. But even if each smoker just smoked less, there would be additional reductions in health care costs, he said.

Cost reductions from reducing smoking would continue and likely grow over the long term.

“Because some health risks linked with smoking, such as cancer, can take years to fully manifest, these savings would be likely to grow with each passing year,” Glantz said.

The paper shows predicted reductions in Medicaid costs by each state.