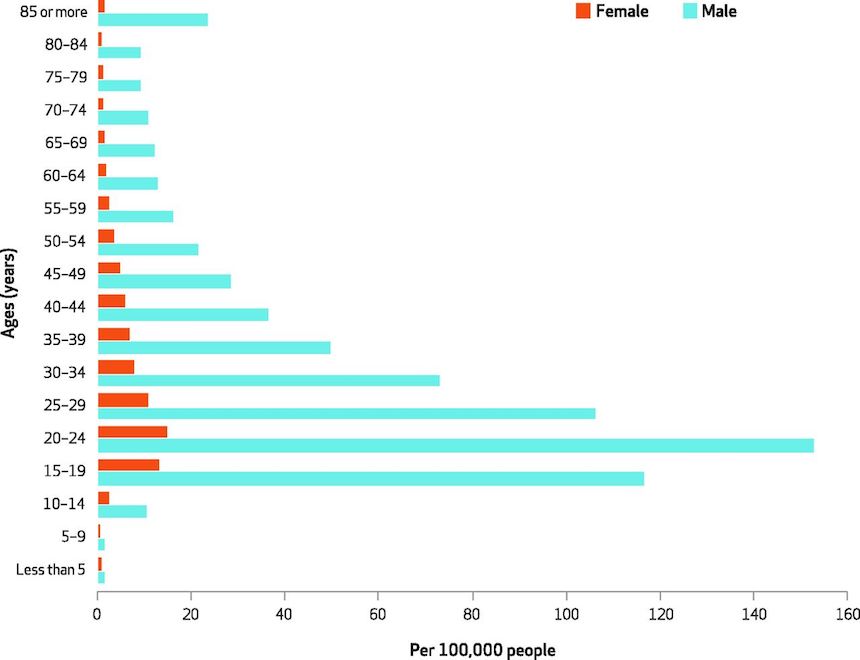

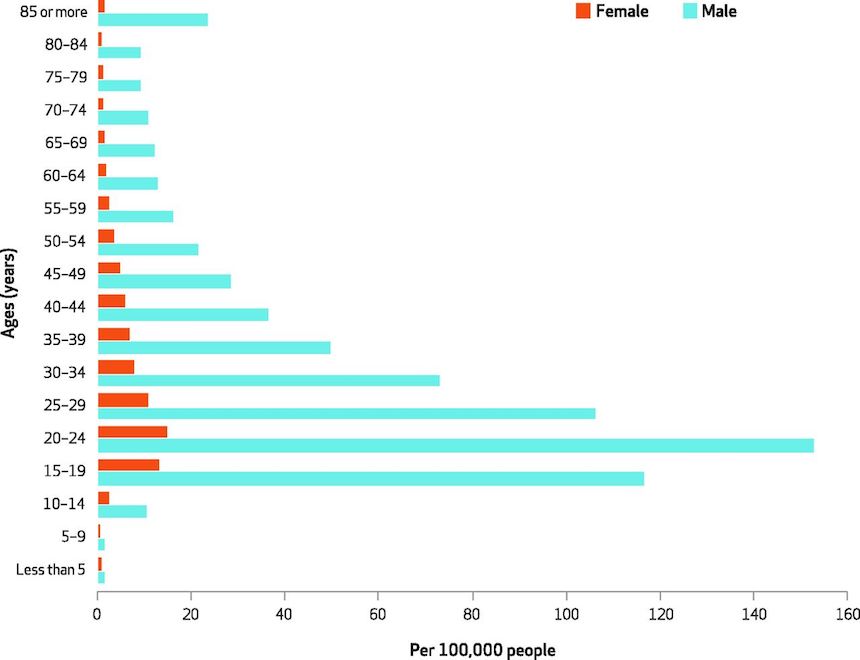

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data for 2006–14 from the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample.

A new Johns Hopkins study of more than 704,000 people who arrived alive at a United States emergency room for treatment of a firearm-related injury between 2006 and 2014 finds decreasing incidence of such injury in some age groups, increasing trends in others, and affirmation of the persistently high cost of gunshot wounds in dollars and human suffering.

A report on the analysis, published in the October issue of Health Affairs, is designed to highlight updated trends in types of firearm injuries and the kinds of firearms commonly used over time.

“Much of the existing literature on firearm-related injuries focuses on pre-hospital statistics with limited data evaluating contemporary estimates for firearm-related injuries,” says Faiz Gani, M.D., a research fellow at the Johns Hopkins Surgery Center for Outcomes Research.

Although firearm-related deaths are the third leading cause of injury-related deaths in the United States, efforts to understand national trends in incidence, prevalence and risk factors, as well as a quantifiable financial cost of firearm-related injuries, have been limited, Gani says.

Johns Hopkins Medicine says that Gani and colleagues, using the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Nationwide Emergency Department Sample, the largest all-payer emergency department (ED) database, analyzed data from a nationally representative sample of 704,916 patients in the U.S. who arrived at an emergency room alive for treatment of a firearm injury from 2006 to 2014. Approximately 89 percent of the patients in the study group were men, with over 49 percent of patients age 18-29 years.

The study took into consideration social, economic and geographic differences; existing illnesses, including mental health disorders; the presence of substance abuse; injury severity; intent of injury (“unintentional,” “suicide,” “assault,” “legal” and “undetermined”); and the type of firearm used.

The research team found that firearm injuries were nine-fold higher among male than female patients (45.8 ED visits per 100,000 versus 5.5 per 100,000) and were highest among males 20 to 24 years old (152.8 per 100,000).

The average ED and inpatient charges annually were $5,254 and $95,887, respectively, resulting in approximately $2.8 billion in annual ED and inpatient charges for the group studied. Gani notes that over half of patients in the study sample were uninsured or self-paying, which means they either bear the burden of the actual hospital charges, or these charges are unrecovered and add to the overall uncompensated care provided by hospitals and health care systems.

The overall incidence of ED admissions for firearm-related injuries decreased from 27.9 visits per 100,000 in 2006 to 21.5 per 100,000 in 2013, representing a 22.9 percent decline. However, ED visits generally increased for those older than 30 years and increased overall for the entire study population in 2014 to 26.6 visits per 100,000.

The proportion of patients who arrived with a previously diagnosed mental health disorder rose over the study period (from 5.3 percent to 7.5 percent); and the proportion of patients injured by unintentional firearm-related injury increased (from 33.7-37.4 percent).

The majority of patients were injured by assault (49.5 percent) or unintentional injury (35.3 percent). Attempted suicide accounted for 5.3 percent.

Suicide attempts were twofold higher among Medicare enrollees (i.e., those over age 65) than among patients enrolled in other insurance plans. Patients who attempted suicide were also more likely to be in the highest income quartile, while those with assault-related injuries were more likely to be in the lowest income quartile.

The incidence of mental health disorders was highest (40 percent) among patients injured by attempted suicide. The incidence of mental health disorders was also higher among patients injured by hunting (12.6 percent) or military grade rifles (12.5 percent).

Over the study, a total of 8.3 percent of patients died in the ED or as an inpatient after their injury. Mortality was highest among older patients age 60 years or more (23.3 percent), those who sustained more severe injuries (32.7 percent) and those injured in an attempted suicide (38.5 percent).

Gani says the study’s main limitation is that it did not account for pre-hospital deaths or those who didn’t go to an ED after a firearm-related injury, so it likely underestimates the overall burden of firearm-related injuries, but he believes the new data paints an updated picture of gun violence trends.

“Until people are aware of the problem’s full extent, we can’t have the best informed discussions to guide policy,” Gani says.

— Read more in Faiz Gani et al., “Emergency Department Visits For Firearm-Related Injuries In The United States, 2006–14,” Health Affairs 36, no. 10 (October 2017): 1729-38 (doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0625)