First-year doctors, or interns, spend 87 percent of their work time away from patients, half of which is spent interacting with electronic health records, according to a new study from researchers at Penn Medicine and Johns Hopkins University. Of the 13 percent of time spent interacting with patients face-to-face, much of that is still spent multitasking. As the largest study to look at how young doctors spend their work day, this research sought to understand what medical residents did while in training, such as how much time they spent in education and patient care. The study was published in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“This objective look at how interns spend their time during the work day reveals a previously hidden picture of how young physicians are trained, and the reality of medical practice today,” said lead author Krisda Chaiyachati, MD, an assistant professor of Medicine in the Perelman School of Medicine of the University of Pennsylvania. “Our study can help residency program leaders take stock of what their interns are doing and consider whether the time and processes are right for developing the physicians we need tomorrow.”

Attempting to gauge the time doctors-in-training spend during their shifts, this research is a part of a larger effort known as the Individualized Comparative Effectiveness of Models Optimizing Patient Safety and Resident Education (iCOMPARE) study. This multi-year study, funded by the National Institute of Health (NIH) and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), seeks to better understand the effects of shift lengths on young doctors and their patients.

Last month, two other studies published in the New England Journal of Medicine from iCOMPARE showed that first-year doctors did not experience chronic sleep loss nor was patient safety affected when doctors-in-training were allowed to work longer shifts than had previously been permitted by the ACGME.

The current study analyzed data from six different internal medicine programs that took part in the national iCOMPARE study. Researchers recorded the activities of 80 interns over three months in 2016, gathering data on 194 shifts spanning 2,173 hours. All activities were classified into categories, including direct patient care, indirect patient care, and education. Direct patient care included time when the interns spoke directly with patients or their family; indirect patient care involved things like working in the medical record, communication with other clinicians, or viewing images; and education included studying and time spent being taught while in the hospital.

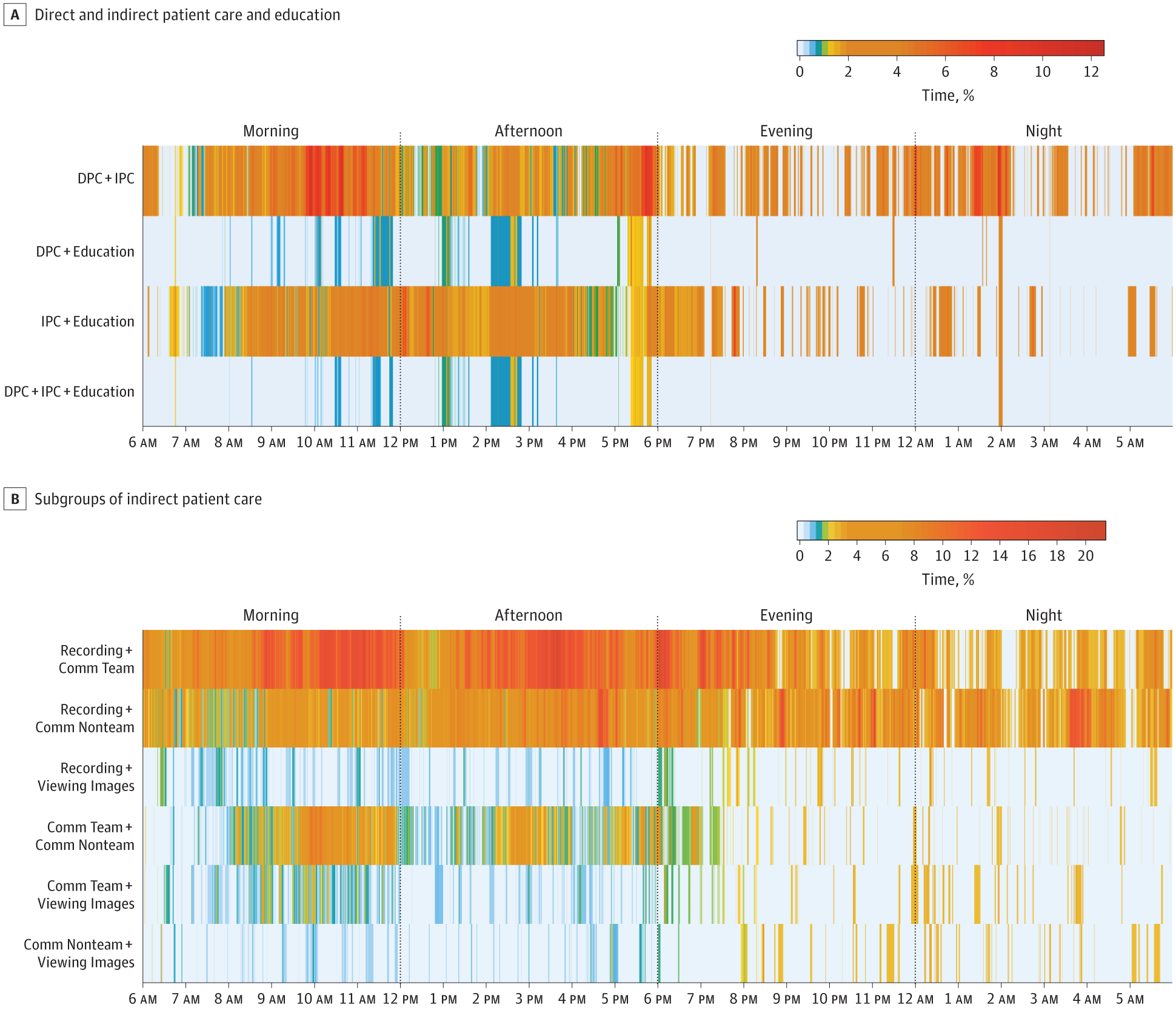

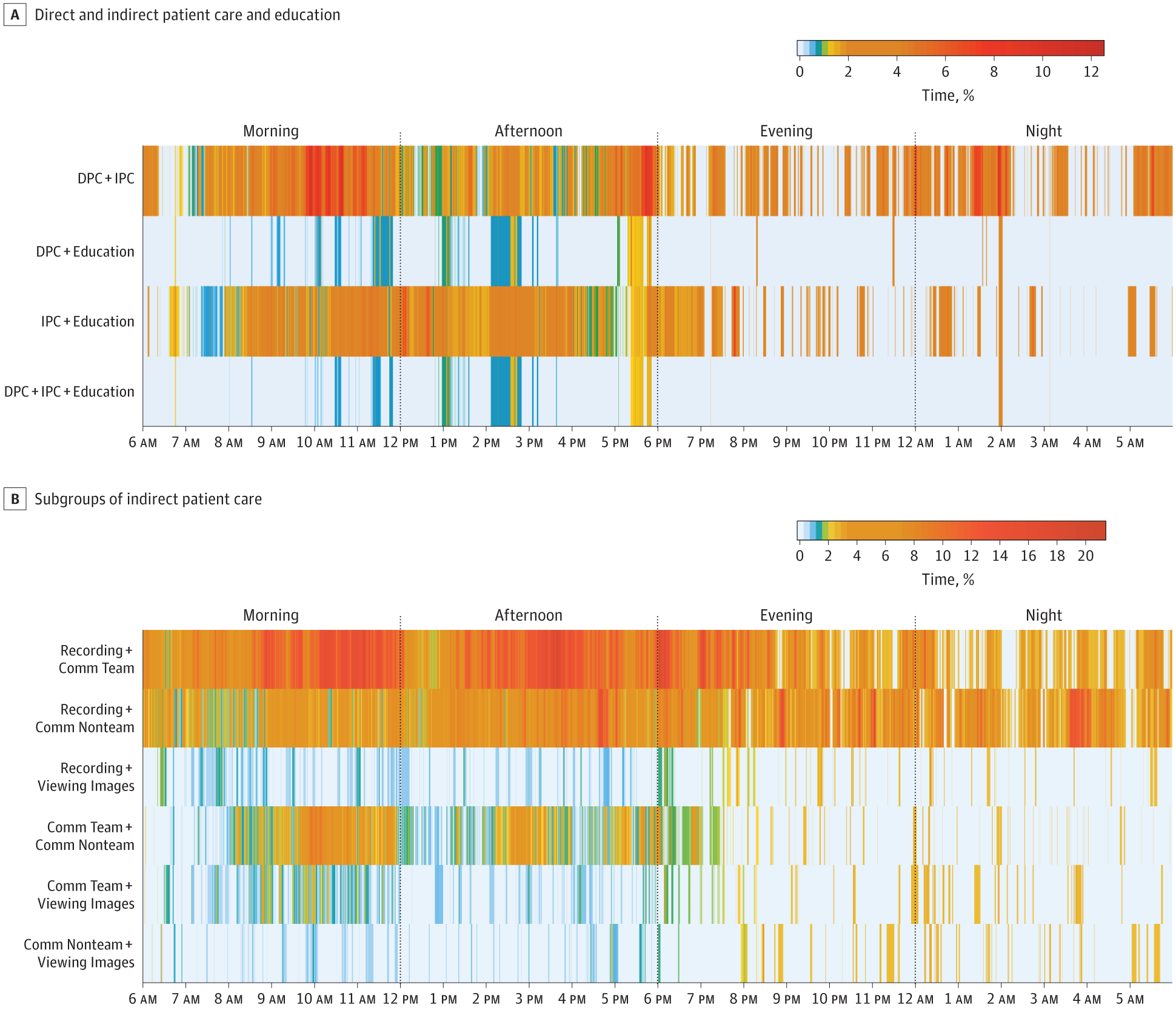

Interns spent the most time performing indirect patient care, taking up an average of 15.9 hours of a 24-hour period–almost five times more hours than the next most common activity, direct patient care, which accounted for three hours of the day. Education was the third-highest category of intern time, attributed to 1.8 hours.

Although interns are spending a significant amount of time not interacting directly with patients, Chaiyachati added that it’s too early to tell “whether or not how interns allocate their time is ‘good’ or ‘bad.'” That could come with further research into how time spent on these shifts affects patient care or physician well-being.

“Indirect patient care has tradeoffs,” Chaiyachati said. “If it takes time away to the point that patients feel like we aren’t listening to their needs or we lose out on human interactions that provide physicians with a sense of purpose, that is a bad thing. But if it helps us diagnose diseases more efficiently, then maybe that’s not that bad in the end.”

When the researchers analyzed four different time periods (separated into six-hour periods: morning, afternoon, evening, and night), they found no significant differences. But multitasking was common throughout. Roughly 25 percent of interns’ time interacting with patients occurred at the same time as coordinating care or updating medical records.

“I think increased multitasking is a side effect of our current system,” Chaiyachati said. “It’s not simply that we are doing more work or we have more tasks in our day-to-day. We are trying to do more in a fixed amount of time.”

Researchers note that this study can provide an important baseline that training programs and hospitals may use when adjusting programs, shifting responsibility for tasks to other health care providers, or automating processes. In that vein, the iCOMPARE team is continuing to comb through its data to find clues about how the work day could change so that doctors in training experience less burnout or improve their professional satisfaction while in training.