The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) may have increased the threat of COVID-19 infection in the Black community and among some other racial and ethnic minority groups when the agency updated its mask guidance last May, according to a new commentary in the Journal of General Internal Medicine by two colleagues at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). At the time, the CDC announced that fully vaccinated people could go without masks in most circumstances, a policy recommendation that was intended to help restore a sense of normalcy, yet ignored certain realities that left some groups vulnerable, the authors argue.

A critical problem with the CDC’s May mask guidance was that there is no way to tell whether a person is fully vaccinated against COVID-19, says Simar Bajaj, a research fellow at MGH. That meant that the CDC was relying on the honor system to ensure that unvaccinated people continued to wear masks. However, earlier research indicates that people often lie about personal health information to avoid being judged, notes Bajaj. “Without a way to verify vaccination status, everyone is going to unmask,” he says, dooming the CDC’s mask guidance to fail.

Blacks in the United States were the group most likely to suffer the consequences of that failure, for a number of reasons, say Bajaj and his coauthor, Fatima Cody Stanford, MD, MPH, MPA, MBA, who is director of equity in MGH’s endocrinology division. For example, at around the time the CDC announced the mask guidance in mid May, just 28 percent of Black Americans had received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, compared to 42 percent of white Americans and 52 percent of Asians. “That’s a huge gap,” says Bajaj, who says it’s partly due to vaccine hesitancy that “is a product of everyday racism that Blacks face when navigating the health system.”

What’s more, Black Americans are far more likely than white Americans to be employed in essential jobs, meaning they can’t lower their risk for infection by working remotely. Black Americans have more medical comorbidities, which made those who became infected more likely to become seriously ill. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, Blacks have had disproportionately high rates of rates of infection with the virus, hospitalization and death, point out Bajaj and Stanford.

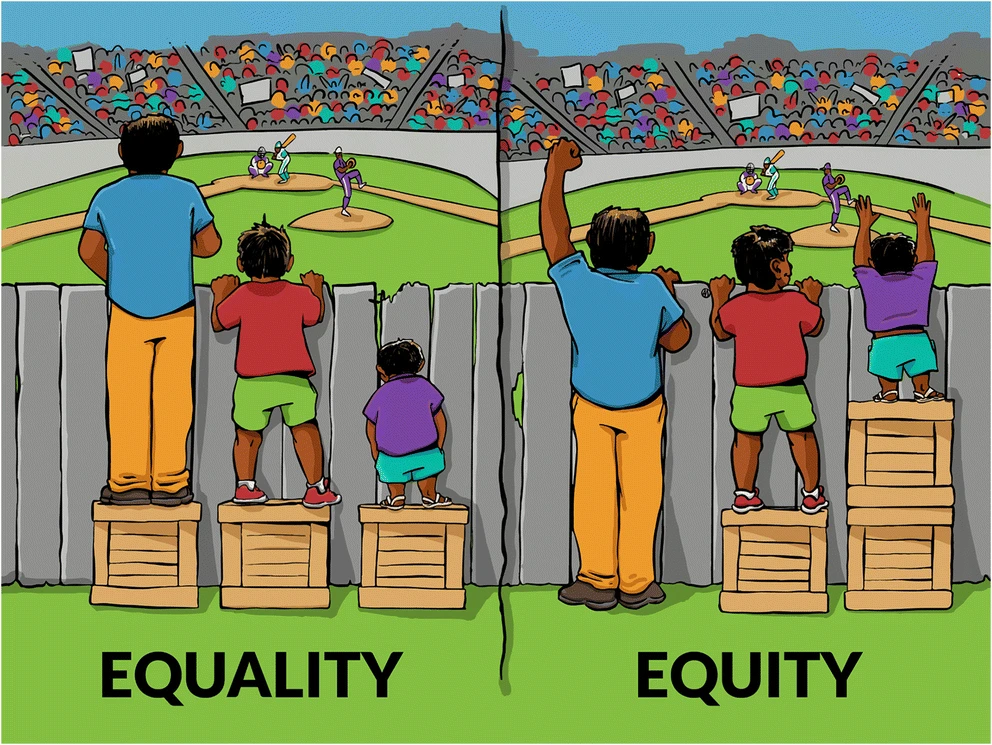

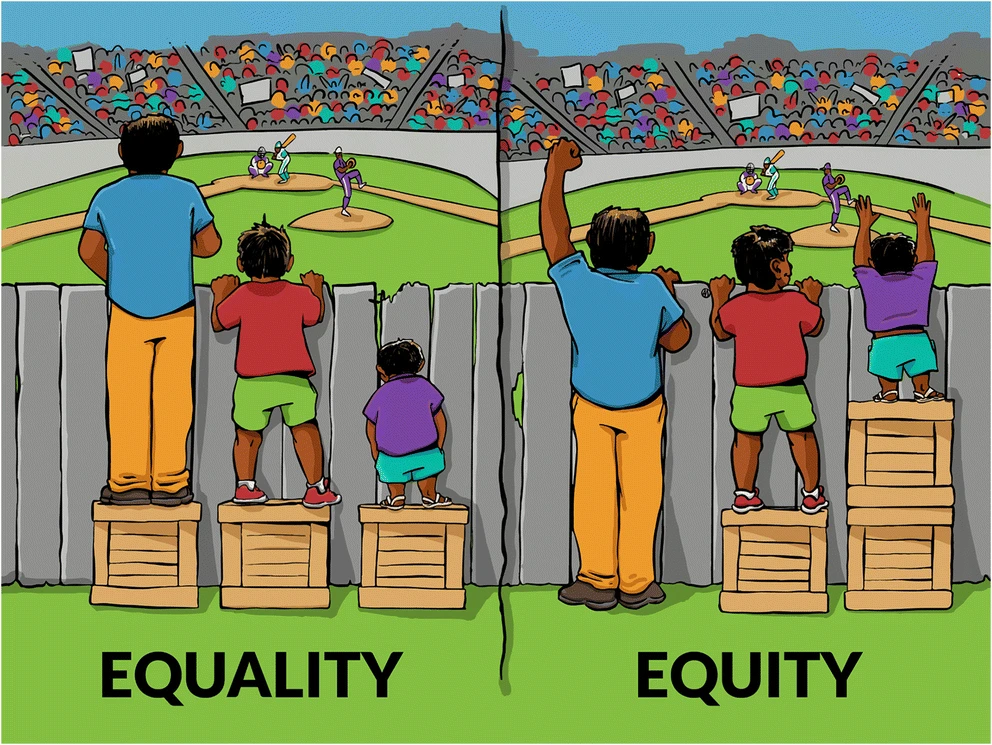

All of these factors made the CDC guidance a threat to the Black community. “When you issue this one-size-fits-all guidance, it should come as no surprise that it could deleteriously impact communities that have been hurt the most already,” says Bajaj. A more nuanced approach, he suggests, might have used “quantitative benchmarks” to determine when it’s safe for a community to unmask, says Bajaj. One approach might be to set goals for what proportion of a community must be fully vaccinated before unmasking is recommended in a state, possibly with higher thresholds in certain racial or ethnic communities, he suggests. Digital health passes that could verify vaccination status are another tool that the CDC could explore.

Their Journal of General Internal Medicine “Viewpoint” article had already been accepted for publication when, in late July, the CDC changed its mask guidance once again, citing new scientific data about the rapidly spreading Delta variant of the COVID-19 virus—in particular, the fact that vaccinated people can transmit the variant. The revised advice encouraged vaccinated people in counties where transmission of the virus is “substantial” or “high” to wear a mask while in indoor public places. To Bajaj, that’s a step in the right direction, since the new guidance is using its own quantitative benchmark—degree of transmission in a county—to determine whether masks are necessary for vaccinated people.

“But it’s too little, too late. Once you have swung the pendulum in the direction of abandoning all caution, it’s hard to walk it back,” says Bajaj, adding that public health authorities should focus on increasing vaccination rates overall, including in communities of color, and promoting greater health equity: the idea of removing barriers to good health for all. “If we continue the current state of affairs, it will be a tale of two pandemics—one in the highly vaccinated, majority-white, suburban areas, and another ripping through and devasting minority communities,” says Bajaj. “I think that’s an unacceptable proposition.”