Imperial researchers have discovered a hidden mechanism within hair follicles that allow us to feel touch.

Previously, touch was thought to be detected only by nerve endings present within the skin and surrounding hair follicles. This new research from Imperial College London has found that that cells within hair follicles – the structures that surround the hair fibre – are also able to detect the sensation in cell cultures.

The researchers also found that these hair follicle cells release the neurotransmitters histamine and serotonin in response to touch – findings that might help us in future to understand histamine’s role in inflammatory skin diseases like eczema.

Lead author of the paper Dr. Claire Higgins, from Imperial’s Department of Bioengineering, said: “This is a surprising finding as we don’t yet know why hair follicle cells have this role in processing light touch. Since the follicle contains many sensory nerve endings, we now want to determine if the hair follicle is activating specific types of sensory nerves for an unknown but unique mechanism.”

A touchy subject

We feel touch using several mechanisms: sensory nerve endings in the skin detect touch and send signals to the brain; richly innervated hair follicles detect the movement of hair fibres; and sensory nerves known as C-LTMRs, that are only found in hairy skin, process emotional, or ‘feel-good’ touch.

Now, researchers may have uncovered a new process in hair follicles. To carry out the study, the researchers analysed single cell RNA sequencing data of human skin and hair follicles and found that hair follicle cells contained a higher percentage of touch-sensitive receptors than equivalent cells in the skin.

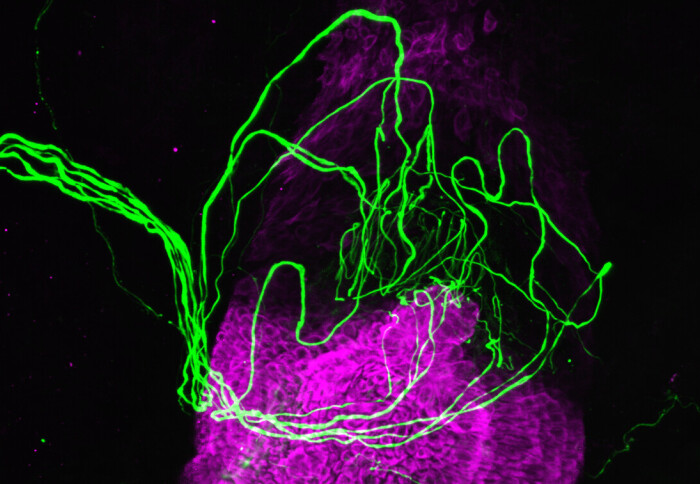

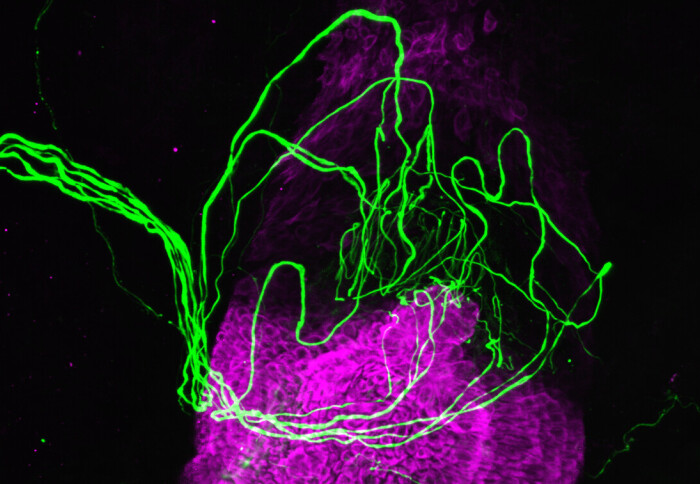

They established co-cultures of human hair follicle cells and sensory nerves, then mechanically stimulated the hair follicle cells, finding that this led to activation of the adjacent sensory nerves.

They then decided to investigate how the hair follicle cells signalled to the sensory nerves. They adapted a technique known as fast scan cyclic voltammetry to analyse cells in culture and found that the hair follicle cells were releasing the neurotransmitters serotonin and histamine in response to touch.

When they blocked the receptor for these neurotransmitters on the sensory neurons, the neurons no longer responded to the hair follicle cell stimulation. Similarly, when they blocked synaptic vesicle production by hair follicle cells, they were no longer able to signal to the sensory nerves.

They therefore concluded that in response to touch, hair follicle cells release that activate nearby sensory neurons.

The researchers also conducted the same experiments with cells from the skin instead of the hair follicle. The cells responded to light touch by releasing histamine, but they didn’t release serotonin.

Dr. Higgins said “This is interesting as histamine in the skin contributes to inflammatory skin conditions such as eczema, and it has always been presumed that immune cells release all the histamine. Our work uncovers a new role for skin cells in the release of histamine, with potential applications for eczema research.”

The researchers note that the research was performed in cell cultures, and will need to be replicated in living organisms to confirm the findings. The researchers also want to determine if the hair follicle is activating specific types of sensory nerves. Since C-LTMRs are only present within hairy skin, they are interested to see if the hair follicle has a unique mechanism to signal to these nerves that we have yet to uncover.