The prevalence of CHD is approximately nine per 1,000 live births, and overall survival rates have steadily increased for even the most complex diseases; however, these patients face many other health obstacles and challenges including the risk of long-term morbidity, re-intervention, length of hospitalization, neurodevelopmental outcomes and more.

“Obtaining the best outcomes requires impact at multiple levels, including patients and caregivers, individual clinicians, the medical team and healthcare system,” Anwar said. “3-D printing is a disruptive technology that is impacting each of these key areas in CHD.” The adoption of 3-D printing in health care is relatively recent, with the most growth seen in cardiology in the past decade.

“3-D printing is rapidly evolving in medicine, with technical improvements in printers and software fueling new and exciting applications in patient care, innovation and research,” said Shafkat Anwar, MD, pediatric cardiologist at Washington University in St. Louis, School of Medicine and the lead author of the paper.

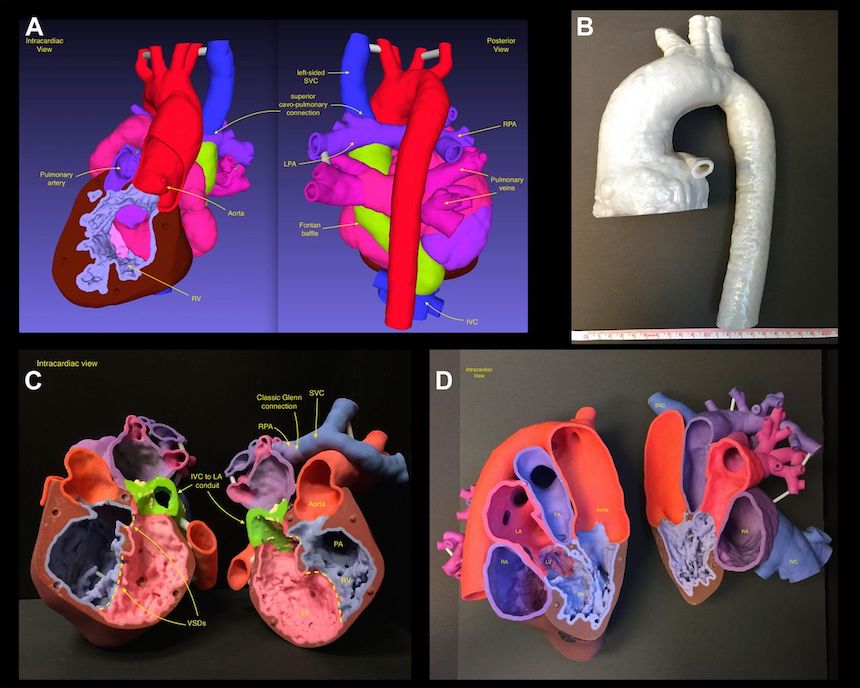

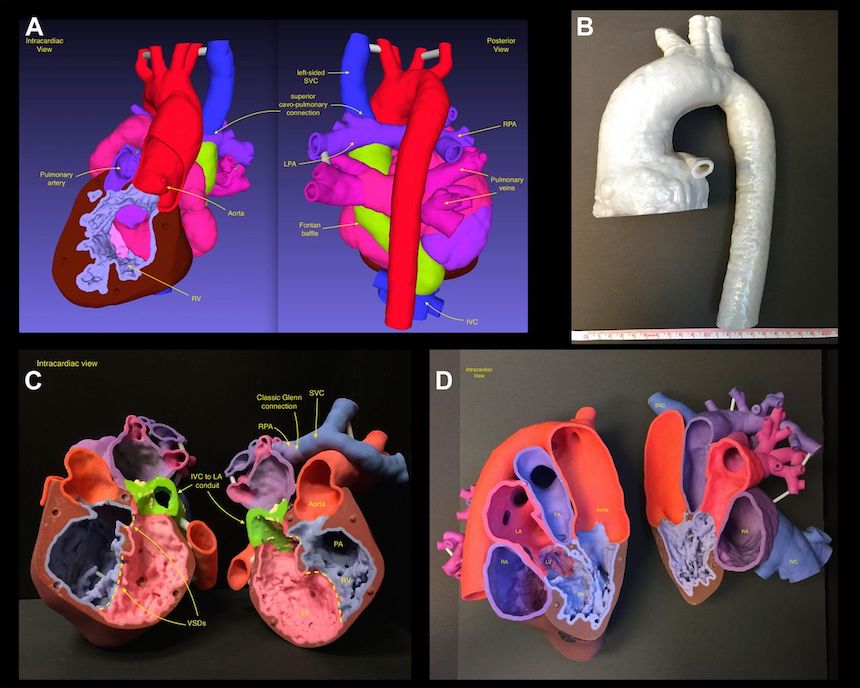

In cardiovascular 3-D printing, the 3-D model is a replica of a patient’s anatomy. These models may be used for precise pre-surgical planning and simulation. This may potentially reduce time spent in the operating room and result in fewer complications.

According to the review, 3-D printing also has the potential to bring transformative change in the education and training of physicians. This technology may lead to an educational shift from an apprenticeship model to a simulator-based learning method that augments traditional mentored training. 3-D models in CHD can reduce the learning curve for cardiac trainees in three key areas–understanding complex 3-D anatomy, high-fidelity simulation experiences and exposure to rare cases. Experienced practitioners can also benefit by using models for lifelong learning, maintenance of certification or for practice before challenging cases.

Additionally, 3-D models serve a communicative purpose as well. Models can be used between specialists to discuss pathology, surgical plans, anticipated outcomes and peri-operative care, which may reduce medical errors. Models can also be used to help the medical team provide patients and caregivers with a better understanding of the disease process, risks, benefits and alternatives.

“The ultimate viability of medical 3-D printing will in large part depend on the impact it has on improving patient care,” Anwar said.

Anwar and colleagues said they predict that the next advances in 3-D printing will likely be driven by improvements in printer technology and print materials. Tissue mimicking materials, which would enable the creation of more life-like models that replicate a patient’s unique anatomy and physiology, are currently in development. As models become more realistic, they may be used to study pathophysiology–or the functional changes observed from a particular disease or syndrome–as well as predict long-term outcomes and choose optimal treatment plans or surgical repairs. Finally, while the technology is in its infancy, there is the potential to print living tissue.

While this technology has the potential to be game-changing, broad adoption is currently hampered by relatively high costs of modeling and printing.