The language people use on Facebook subtly changes before they make a visit to the emergency department (ED), a new study found. Researchers from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and Stony Brook University’s Computer Science Department compared patients’ Facebook posts to their medical records, which showed that a shift to more formal language and/or descriptions of physical pain, among other changes, reliably preceded hospital visits. Published today in Nature Scientific Reports, the study provides more evidence that social media is often an unseen signal of medical distress and could potentially be used to trigger health care interventions.

“The better we understand the context in which people are seeking care, the better they can be attended to,” said lead author Sharath Chandra Guntuku, PhD, a research scientist in Penn Medicine’s Center for Digital Health. “While this research is in a very early stage, it could potentially be used to both identify at-risk patients for immediate follow-up or facilitate more proactive messaging for patients reporting doubts about what to do before a specific procedure.”

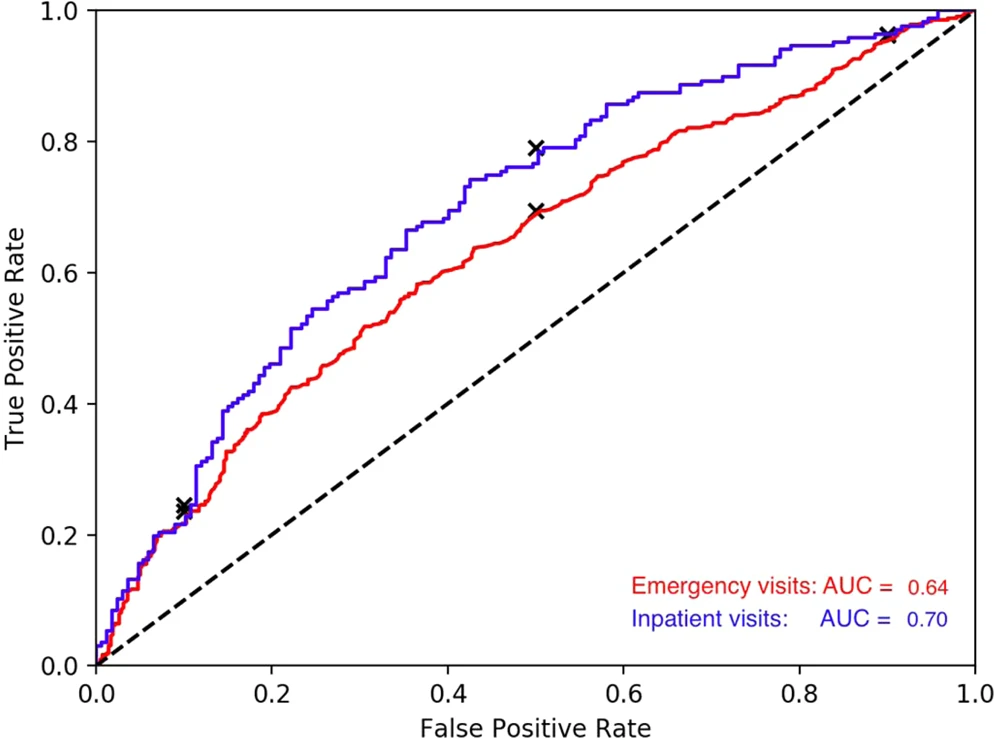

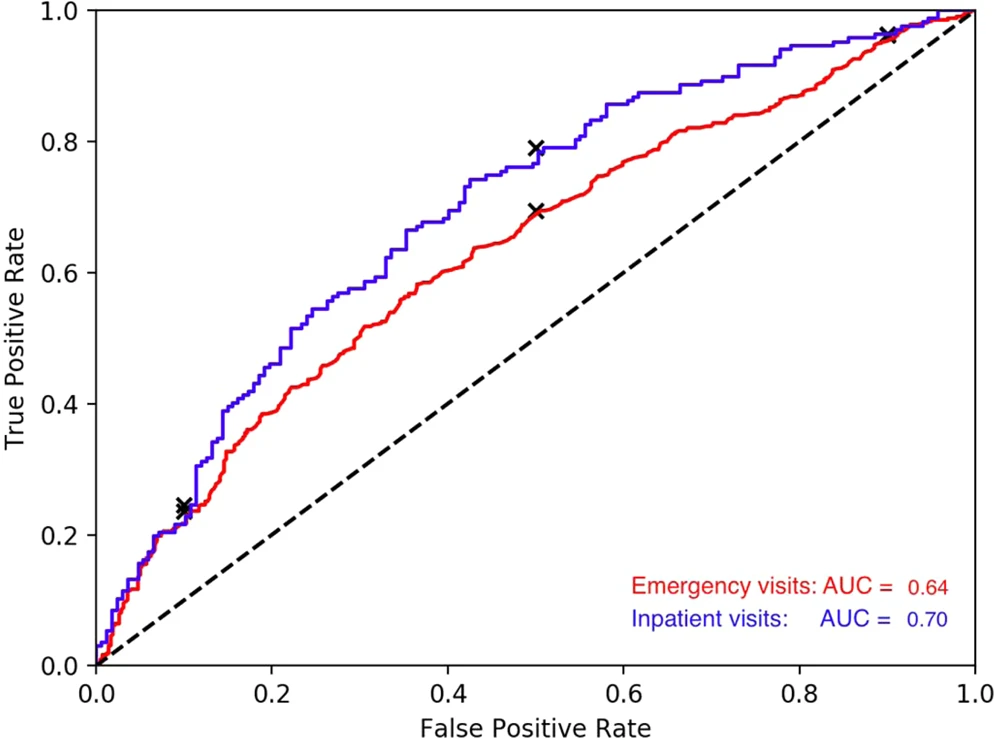

The study’s researchers recruited 2,915 patients at an urban hospital who consented to sharing their Facebook posts and electronic health records (EHRs). Of those patients, 419 had a recent emergency department (ED) visit, ranging from chest pain to pregnancy-related issues. Posts from as early as two-and-a-half months before the date of the patients’ ED visit were analyzed using a machine learning model that processed their language to find changes over time.

Ultimately, it was found that most patients underwent a significant change in language before they went to the ED. Before their visit, patients were less likely to post about leisure (not using words like “play,” “fun,” and “nap”) or use internet slang and informal language (such as using “u” instead of “you”).

As patients got closer to their eventual ED visit, the researchers found that Facebook posts increasingly discussed family and health more. They also used more anxious, worrisome, and depressed language. Study author H. Andrew Schwartz, PhD, an assistant professor of Computer Science at Stony Brook University and a collaborator with the Penn Medicine Center for Digital Health, said that the decrease in informal language “seems to go hand-in-hand” with an increase in anxiety-related language.

“We seem to become more grave and serious when we are unwell,” Guntuku said. “And looking beyond the family mentions data, it’s possible that, when health is down, the need for belonging increases and shows up in what one posts on social media.”

When the researchers looked more closely at the context of some posts, they noticed there might be some clues to patients’ health behaviors related directly to their hospital visit. One post, for example, talked about the patient eating a cheeseburger and fries less than a month before they were admitted for chest pain related to having heart failure. Another patient confirmed that they were following directions from their care team, posting about fasting 24 hours before they had a scheduled surgery.

“How does life affect personal decisions to seek care? How does care affect life? These are the things I would hope that we could fully describe, how people’s everyday lives intermix with health care,” Schwartz said.

This study primarily looked at the change in language before a hospital visit, but a past study involving the paper’s senior author, Raina Merchant, MD, the director of the Center for Digital Health and an associate professor of Emergency Medicine, showed that a person’s depression could be predicted through the language of Facebook posts as far ahead as three months before an official diagnosis. Guntuku said there is evidence that language changes as far out as a month leading up to an ED visit, but “we need a much better understanding of a person’s context” to forecast it accurately. Expressions on social media are just one piece of the puzzle — albeit a highly telling one — so context will come into play when determining the applicability of the Facebook findings to other social media platforms.

“It’s likely that individuals use different platforms to share varying information and that what is revealed on Facebook to an audience of that person’s friend network may be very different from a Twitter or Instagram network,” Merchant said.

Moving forward, the researchers plan to study broader populations and attempt to understand what actionable and interpretable insights can be provided to patients who opted to share their data.