Scientists have identified differences in a group of genes they say might help explain why some people need a lot more sleep — and others less — than most. The study, conducted using fruit fly populations bred to model natural variations in human sleep patterns, provides new clues to how genes for sleep duration are linked to a wide variety of biological processes.

Researchers say a better understanding of these processes could lead to new ways to treat sleep disorders such as insomnia and narcolepsy. Led by scientists with the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), part of the National Institutes of Health, the study will be published on Dec. 14 in PLOS Genetics.

“This study is an important step toward solving one of the biggest mysteries in biology: the need to sleep,” says study leader Susan Harbison, Ph.D., an investigator in the Laboratory of Systems Genetics at NHLBI. “The involvement of highly diverse biological processes in sleep duration may help explain why the purpose of sleep has been so elusive.”

Scientists have known for some time that, in addition to our biological clocks, genes play a key role in sleep and that sleep patterns can vary widely. But the exact genes controlling the duration of sleep and the biological processes that are linked to these genes have remained unclear.

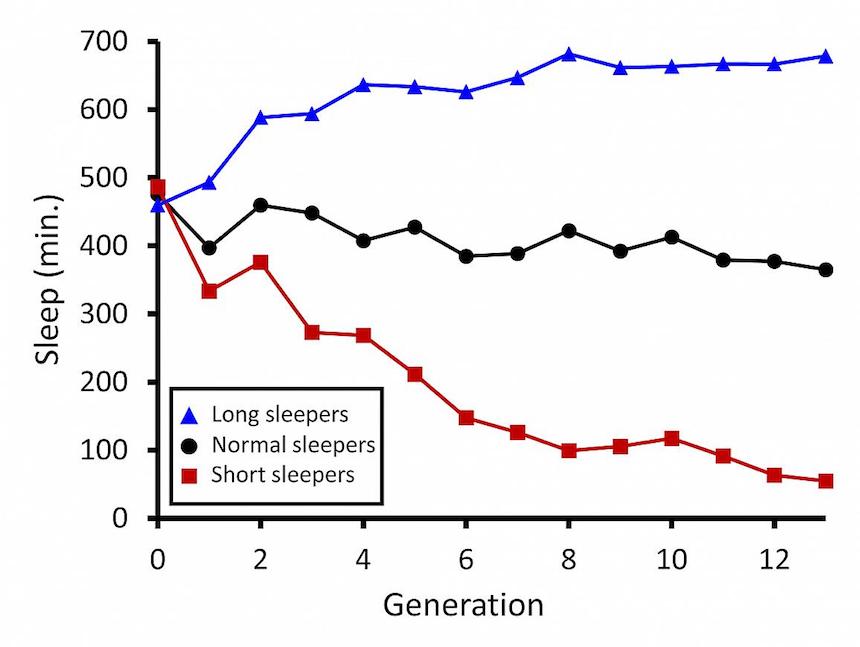

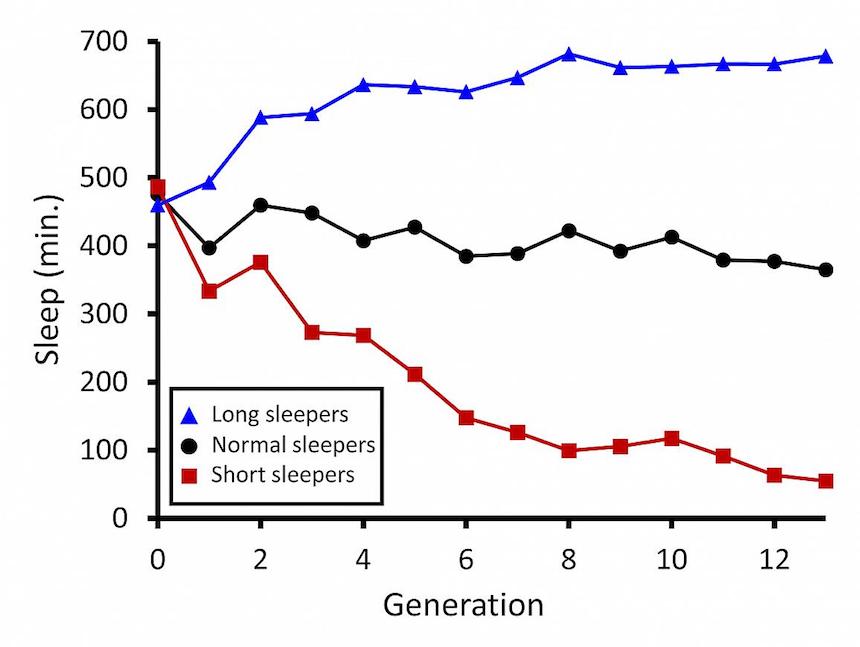

To learn more, scientists artificially bred 13 generations of wild fruit flies to produce flies that were either long sleepers (sleeping 18 hours each day) or short sleepers (sleeping three hours each day). The scientists then compared genetic data between the long and short sleepers and identified 126 differences among 80 genes that appear to be associated with sleep duration. They found that these genetic differences were tied to several important developmental and cell signaling pathways. Some of the genes identified have known functions in brain development, as well as roles in learning and memory, the researchers said.

“What is particularly interesting about this study is that we created long- and short-sleeping flies using the genetic material present in nature, as opposed to the engineered mutations or transgenic flies that many researchers in this field are using,” Harbison said. “Until now, whether sleep at such extreme long or short duration could exist in natural populations was unknown.”

The researchers also found that the lifespan of the naturally long and short sleepers did not differ significantly from the flies with normal sleeping patterns. This suggests that there are few physiological consequences—whether ill effects or benefits — of being an extreme long or short sleeper, they said.